One-child policy

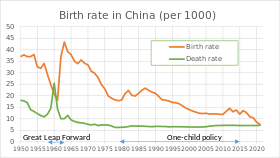

[2] China's family planning policies began to be shaped by fears of overpopulation in the 1970s, and officials raised the age of marriage and called for fewer and more broadly spaced births.

[51] It is also suggested that mathematical terms, graphs, and tables were utilized to form a convincing narrative that presents the urgency of the population problem as well as justifies the necessity of mandatory birth control across the nation.

[52] Arguments started to come out in 1979 suggesting that the excessively rapid population growth was sabotaging the economy and destroying the environment, and essentially preventing China from being a rightful member of the global world.

Though the data is truthful, its arrangement and presentation to readers gave a single message determined by the state: that the population problem is a national catastrophe and immediate remedy is desperately needed.

[55] Social scientists involved in this discussion in the mid-1970s, including Liu Zheng, Wu Cangping, Lin Fude, and Zha Ruichuan, prioritized the Marxist formulation of the population problem.

[86] If the family was not able to pay the "social child-raising fee", then their child would not be able to obtain a hukou, a legal registration document that was required in order to marry, attend state-funded schools, or to receive health care.

The Wan Xi Shao slogan emerged during the 1970s as a response to China's rapid population growth, which was viewed as a major obstacle to the country's economic and social development.

[101] This slogan encapsulated three key principles: marrying later (wan, 晚), spacing pregnancies farther apart (xi, 稀), and having fewer children (shao, 少)[102] and was emblematic of China's national campaign of mandatory birth planning.

These drastic increases in birth-control operations suggest that highly coercive birth planning enforcement was already prevalent in both rural and urban areas, preceding the launch of the one-child policy.

Traditional elements like chubby, healthy-looking babies resonated with people – making them believe that compliance with the policy would yield luck, good fortune, and healthy offspring.

"[47][134] The CNN reporter added that China's new prosperity was also a factor in the declining[129] birth rate, saying, "Couples naturally decide to have fewer children as they move from the fields into the cities, become more educated, and when women establish careers outside the home.

[149] In her fieldwork interviews, Mellors Rodriguez found that middle income urbanites were more receptive to the limitations of the policy because they generally believed that having one child and providing them with all possible opportunities was more important than having additional heirs.

[6]: 193 Anthropologist Yan Yunxiang attributes this decrease to greater acceptance of family planning among the new generation of parents, as well as their increased prioritization of material comforts and individual happiness.

[172] A study by Anderson & Silver (1995) found a similar pattern among both Han and non-Han nationalities in Xinjiang Province: a strong preference for girls in high parity births in families that had already borne two or more boys.

[176] In December 2016, researchers at the University of Kansas reported that the sex disparity in China was likely exaggerated due to administrative under-reporting and delayed registration of females, rather than abortion and infanticide.

In accordance with this high demand, China began defining more restrictions on foreign adoption, including limitations on applicant's age, marital status, mental and physical health, income, family size, and education.

One study by Greenhalgh et al. (2005) found that many urban women in China perceived the one-child policy as positive, as it allowed them to have greater control over their reproductive health and career trajectories.

[198] A study by Mosher (2012) found that women who underwent forced abortions or sterilizations as a result of the one-child policy experienced significant psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and trauma.

In "Gender and elder care in China: the influence of filial piety and structural constraints," authors Zhan and Montgomery suggest that the decline of traditional family support networks began with the establishment of work units in the socialist period.

The authors tested Beijing youths born in several birth cohorts just before and just after the launch of the one-child policy using economic games designed to detect differences in desirable social behaviors like trust and altruism.

"[225] The proposal was prepared by Ye Tingfang, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who suggested that the government at least restore the previous rule that allowed couples to have up to two children.

The closest US location from China is Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, a US dependency in the western Pacific Ocean that generally allows Chinese citizens to visit for 14 days without requiring a visa.

[234] After the initial forced sterilization and abortion campaign in 1983, citizens of urban areas in China disagreed with the standards being placed on them by the government and having complete disregard for basic human rights.

[2] The Chinese government, quoting Zhai Zhenwu, director of Renmin University's School of Sociology and Population in Beijing, estimates that 400 million births were prevented by the one-child policy as of 2011, while some demographers challenge that number, putting the figure at perhaps half that level, according to CNN.

[236] According to a report by the US embassy, scholarship published by Chinese scholars and their presentations at the October 1997 Beijing conference of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population seemed to suggest that market-based incentives or increasing voluntariness is not morally better but that it is, in the end, more effective.

[237] In 1988, Zeng Yi and Professor T. Paul Schultz of Yale University discussed the effect of the transformation to the market on Chinese fertility, arguing that the introduction of the contract responsibility system in agriculture during the early 1980s weakened family planning controls during that period.

[69] A 2003 review of the policy-making process behind the adoption of the one-child policy shows that less intrusive options, including those that emphasized delay and spacing of births, were known but not fully considered by China's political leaders.

"[243][244] According to the UK newspaper The Daily Telegraph, a quota of 20,000 abortions and sterilizations was set for Huaiji County, Guangdong in one year due to reported disregard of the one-child policy.

[246] According to a 2005 news report by Australian Broadcasting Corporation correspondent John Taylor, China outlawed the use of physical force to make a woman submit to an abortion or sterilization in 2002 but ineffectively enforced the measure.

[260][261] A writer for the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs wrote, "The 'one-child' policy has also led to what Amartya Sen first called 'Missing Women', or the 100 million girls 'missing' from the populations of China (and other developing countries) as a result of female infanticide, abandonment, and neglect".