Freedoms of the air

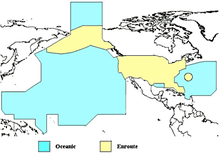

The freedoms of the air are the fundamental building blocks of the international commercial aviation route network.

Several other freedoms have been added, and although most are not officially recognised under broadly applicable international treaties, they have been agreed to by a number of countries.

[3]: 145–146 Even when such services are allowed by countries, airlines may still face restrictions to accessing them by the terms of treaties or for other reasons.

[9] As of the summer of 2007, 129 countries were parties to this treaty, including such large ones as the United States, India, and Australia.

[10] These large and strategically located non-IASTA-member states prefer to maintain tighter control over foreign airlines' overflight of their airspace and negotiate transit agreements with other countries on a case-by-case basis.

[9] Such fees indeed are commonly charged merely for the privilege of the overflight of a country's national territory, when no airport usage is involved.

For example, the Federal Aviation Administration of the U.S., an IASTA signatory, charges overflight fees based on the great circle distance between an aircraft's points of entry into and exit from U.S.-controlled airspace.

Anchorage was similarly used for flights between Western Europe and East Asia, bypassing Soviet airspace, closed until the end of the Cold War.

Flights between Europe and South Africa often stopped at Ilha do Sal (Sal Island) in Cabo Verde, off the coast of Senegal, due to many African nations refusing to allow South African flights to overfly their territory during the Apartheid regime.

[17]: 108 The remaining four freedoms are made possible by some air services agreements but are not 'officially' recognized because they are not mentioned by the Chicago Convention.

An example of a fifth freedom traffic right is an Emirates flight in 2004 from Dubai to Brisbane, Australia and onward to Auckland, New Zealand, where tickets can be sold on any sector.

[22]: 33–34 The negotiations for fifth freedom traffic rights can be lengthy, because in practice the approval of at least three different nations is required.

[7]: 31–32 An example of a multi-sector flight in the mid-1980s was an Alitalia service from Rome to Tokyo via Athens, Delhi, Bangkok and Hong Kong.

[7]: 31–32 Fifth freedom flights remained highly common in East Asia during the 2000s, particularly on routes serving Tokyo, Hong Kong and Bangkok.

In the late 1990s, half of the seats available between the two cities were offered by airlines holding fifth freedom traffic rights.

[17]: 112 Other major markets served by fifth freedom flights can be found in Europe, South America, the Caribbean and the Tasman Sea.

In turn, though, there may be reactionary pressure to avoid liberalizing traffic rights too much in order to protect a flag carrier's commercial interests.

[17]: 110 By the 1990s, fifth freedom traffic rights stirred controversy in Asia because of loss-making services by airlines in the countries hosting them.

However, these were seen as being less valuable than the fifth freedom traffic rights enjoyed by US air carriers via Japan, because of the higher operating costs of Japanese airlines and also geographical circumstances.

From its 1962 initiation of Boeing 707 service to Idlewild (renamed JFK in 1964), flights had intermediate stops at one Middle East airport (Kuwait, Cairo, or Beirut), then two or three European airports, the last of which was always London's Heathrow, with trans-Atlantic service operating between Heathrow and JFK.

[24] Another example is Air Canada, which has pursued a strategy of carrying passengers between the US and points in Europe and Asia through its Canadian hubs.

[25] While sixth freedom operations are rarely legally-restricted, they may be controversial: for example, Qantas has complained that Emirates, Singapore Airlines and other sixth-freedom carriers have unfair advantages in the market between Europe and Australia.

[24] Because the nature of air services agreements is essentially a mercantilist negotiation that strives for an equitable exchange of traffic rights, the outcome of a bilateral agreement may not be fully reciprocal but rather a reflection of the relative size and geographic position of two markets, especially in the case of a large country negotiating with a much smaller one.

It is "trade or navigation in coastal waters, or, the exclusive right of a country to operate the air traffic within its territory".

The unofficial eighth freedom is the right to carry passengers or cargo between two or more points in one foreign country and is also known as cabotage.

Other examples include the Single Aviation Market (SAM) established between Australia and New Zealand in 1996; the 2001 Protocol to the Multilateral Agreement on the Liberalization of International Air Transportation (MALIAT) between Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore; United Airlines' "Island Hopper" route, from Guam to Honolulu, able to transport passengers within the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, although the countries involved are closely associated with the United States.