Petit-Clamart attack

[2] After reassuring a European and Muslim Gaullist crowd fraternizing in Algiers on 4 June 1958, with a historic "I understand you", followed by an unequivocal "Long live French Algeria" in Mostaganem, de Gaulle, once he became President of the Republic in 1959, undertook to complete the decolonization policy that he had initiated in 1943 with Lebanon and Syria during his campaign to rally the colonies to Free France with a view to liberating the metropolitan territory itself occupied by Hitler's Nazi Germany.

[3] On 16 September 1959, de Gaulle used the term "self-determination" for the first time in relation to what was still in the media only "the Algerian affair", certain voices of protest began to arise, which were heard among certain Gaullists in Algeria and in mainland France.

[4] On 24 January 1960, extremist defenders of the maintenance of French Algeria carried out a siege in the Algerian capital, then the second largest city in France, in what would become the "week of the barricades", expecting the support of Massu.

[4] In February 1961, Pierre Lagaillarde and Raoul Salan, who had also gone underground, reached agreement and began the Organisation armée secrète ("Secret Army Organization"), commonly known as OAS.

[4][5][6] In April 1961, following the failure of the generals' putsch—this time aimed at overthrowing de Gaulle, who talked with a delegation of separatists, and replacing his authority with a military junta—the OAS increased its clandestine operations.

[5] These actions, the most radical of which involved political assassination and terrorism, were carried out both in the French departments of Algeria and in mainland France, the OAS having a "Metro" branch, by the "Commando Delta".

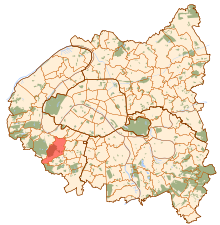

[7][8][9] On 22 August 1962, at around 7:45 pm (UTC+1), two unmarked Citroën DS 19s escorted by two motorcyclists left the Élysée Palace to take de Gaulle and his wife Yvonne to the Villacoublay Air Base, where they took an airplane to Saint-Dizier to then reach Colombey-les-Deux-Églises by road.

In the first car were Charles and Yvonne DeGaulle, as well as Colonel Alain de Boissieu, son-in-law and aide-de-camp of the president, who was seated next to the driver, Gendarme Francis Marroux.

[12][13] The commando was composed of twelve members, including Jean Bastien-Thiry, Alain de La Tocnaye, László Varga, Lajos Marton, and Gyula Sári, all of whom were fiercely anti-communist.

Five men (Buisines, Varga, Sári, Bernier and Marton) were in a yellow Renault Estafette, equipped with machine guns; La Tocnaye was on board a Citroën ID 19, with Georges Watin and Prévost, equipped with submachine guns; the final vehicle was a Peugeot 403 van, from which Condé, Magade and Bertin were hidden from view, also with automatic weapons.

During the first session, nine accused commando members appeared before the Military Court of Justice on 28 January 1963: Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry defended by Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour, Alain de La Tocnaye, Pascal Bertin, Gérard Buisines, Alphonse Constantin, Étienne Ducasse, Pierre-Henri Magade, Jacques Prévost and László Varga.

Six other defendants were tried in absentia; those absent, on the run, were Serge Bernier, Louis de Condé, Gyula Sári, Lajos Marton, Jean-Pierre Naudin, and Georges Watin.

[26] This Military Court of Justice had been declared illegal by the Conseil d'État on 19 October 1962, on the grounds that it infringed the general principles of law by the absence of any appeal against its decisions.

Discussion tended to focus on three points: the virulence of Bastien-Thiry's criticism of de Gaulle's policies regarding Algeria; the fact that the condemned were finally pardoned with the exception of one; and the expeditious nature of the sentence.

The day after the execution, in L'Express, journalist Jean Daniel wrote, "In fact, the inhumanity of the sovereign ends up overwhelming even his supporters".

"[31] According to authors such as Jean-Pax Méfret and member of the commando Lajos Marton, the conspirators said they had benefited from support within the Élysée from Commissioner Jacques Cantelaube.

[29][32] In 2015, Marton revived the hypothesis of the involvement of the Minister of Finance, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who, under the code name "B12", would have informed the OAS of de Gaulle's movements.

[32] There is an alternative and controversial thesis that the primary aim of the operation was not to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle in Clamart, but to kidnap him to bring him before the Council tribunal.

[35][36] Marton said that, in 1961, Bastien-Thiry contacted Colonel Antoine Argoud, disgraced since the "week of the barricades", who had been appointed to a "closet" post in Metz, where he spent most of his time preparing the putsch of 1961.

Bastien-Thiry subsequently made contact with Jean Bichon, a former resistance fighter and liaison officer between the "Old Staff" and the High Command of the OAS.

On 24 April, General Paul Gardy announced on Oran pirate radio (the only transmitter of the OAS) that he was taking his place at the top of the organization chart, but command was also claimed by Jean-Jacques Susini.

[41][42] Two years after the attack, the damaged DS 19 was restored, the bullet holes were erased from the exterior, and the car was sold on 15 October 1964 to General Robert Dupuy, former military commander of the Élysée.