Operation Downfall

[4] At the time, the development of the atomic bomb was a very closely guarded secret, known only to a few top officials outside the Manhattan Project (and to the Soviet espionage apparatus, which had managed to infiltrate or recruit agents within the program, despite the tight security around it), and the initial planning for the invasion of Japan did not take its existence into consideration.

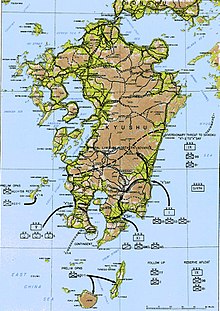

These were responsible for attacking Japanese airfields and transportation arteries on Kyushu and Southern Honshu (e.g. the Kanmon Tunnel) and for gaining and maintaining air superiority over the beaches.

Following the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, plans were also made to transfer some of the heavy bomber groups of the veteran Eighth Air Force to airbases on Okinawa to conduct strategic bombing raids in coordination with the Twentieth.

Had reinforcements been needed at an early stage of Olympic, they would have been diverted from US forces being assembled for Coronet—for which there was to be a massive redeployment of units from the US Army's Southwest Pacific, China-Burma-India and European commands, among others.

The Japanese planned to commit the entire population of Japan to resisting the invasion, and from June 1945 onward, a propaganda campaign calling for "The Glorious Death of One Hundred Million" commenced.

Early in the war (such as at Tarawa), the Japanese employed strong defenses on the beaches with little or no manpower in reserve, but this tactic proved vulnerable to pre-invasion shore bombardment.

Weapons, training and uniforms were generally lacking: many were armed with nothing better than antiquated firearms, molotov cocktails, longbows, swords, knives, bamboo or wooden spears, and even clubs and truncheons: they were expected to make do with what they had.

[60] The United States Strategic Bombing Survey subsequently estimated that if the Japanese managed 5,000 kamikaze sorties, they could have sunk around 90 ships and damaged another 900, roughly triple the Navy's losses at Okinawa.

This involved adding more fighter squadrons to the carriers in place of torpedo and dive bombers, and converting B-17s into airborne radar pickets in a manner similar to present-day AWACS.

[66] The buildup of Japanese troops on Kyūshū led American war planners, most importantly General George Marshall, to consider drastic changes to Olympic, or replacing it with a different invasion plan.

Dropping or spraying the herbicide was deemed most effective; a July 1945 test from an SPD Mark 2 bomb, originally crafted to hold biological weapons like anthrax or ricin, had the shell burst open in the air to scatter the chemical agent.

[76] The Joint Staff planners, taking note of the extent to which the Japanese had concentrated on Kyūshū at the expense of the rest of Japan, considered alternate places to invade such as the island of Shikoku, northern Honshu at Sendai, or Ominato.

[78]However, King was prepared to oppose proceeding with the invasion, with Nimitz's concurrence, which would have set off a major dispute within the US government: At this juncture, the key interaction would likely have been between Marshall and Truman.

[79]Unknown to the Americans, the Soviet Union also considered invading a major Japanese island, Hokkaido, by the end of August 1945,[80] which would have put pressure on the Allies to act sooner than November.

"[86] Due to the nature of combat in the Pacific Theater and the characteristics of the Japanese Armed Forces, it was accepted that a direct invasion of mainland Japan would be very difficult and costly.

"[88] Despite the high numbers, by the spring of 1945 a figure of 500,000 battle casualties for the projected invasion was widely used in briefings, while totals of closer to a million were used for actual planning purposes.

[89] U.S. planners hoped that by seizing a few vital strategic areas they could establish "effective military control" over Japan without the need to clear the entire archipelago or defeat the Japanese on mainland Asia, thereby avoiding excessive losses.

[97] Neither Hull nor Grew objected to Hoover's estimate, but Stimson forwarded his copy of "Memo 4" to Marshall's deputy Chief of Staff, General Thomas T. Handy.

As with the "worst case" scenario from JCS 924, Handy wrote that "under our present plan of campaign" (emphasis original), "the estimated loss of 500,000 lives [...] is considered to be entirely too high."

"[99] Appalled at the prospect of an impending bloodbath, Truman ordered a meeting scheduled for June 18, 1945, involving the JCS, Stimson, and Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal.

To support the meeting, the Joint War Plans Committee (JWPC) hastily assembled a table illustrating the casualties that could be expected in an invasion of Japan based on the experience of the Battle of Leyte.

"[102] Throughout the summer, as the intelligence picture concerning Japanese Army strength in the Home Islands became more and more unfavorable, together with new data from the fighting on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, casualty predictions were continually revised upward.

During the first week of August, approximately 50 reporters from the United States, Britain, and Australia were given an "off the record" briefing at General MacArthur's headquarters in Manila, where they were informed that final operations against Japan could result in up to 1 million American casualties.

3, MacArthur's intelligence chief, Major General Charles A. Willoughby, concluded that destroying "two to two and a half Japanese divisions [exacts] a total of 40,000 American battle casualties on land."

The estimate excluded losses from "the shattering kamikaze attack," combat against Naval ground forces personnel and militia, and any reinforcements the Japanese might have been able to bring in to the battle areas.

Former Ensign Kiyoshi Endo, an Iwo Jima survivor, later recalled: "The number of deaths on the Japanese side was much larger, because the Americans rescued and treated their injured.

[123] Under the Ketsu-Go (結語, "conclusion") plan, all divisions assigned to coastal defense were ordered to stand and fight "even to utter annihilation," and heavy counterattacks by reserves aimed to force a decisive battle near the beachheads.

[125] Given their chosen tactics, American military historian Richard B. Frank concluded that "it is hard to imagine that fewer than [40 to 50%]" of Japanese soldiers and sailors in the invasion areas "would have fallen by the end of the campaign.

[128] Army Service Forces planners assessed that approximately one third of Japanese civilians within the invasion areas on Kyushu and Honshu would flee as refugees or die, leaving the remainder (including wounded and sick) to be cared for by the occupation authorities.

In January 1946, future Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida warned that unless emergency food aid was rushed to Japan, up to 10 million people could starve to death by the end of 1946.