Operation Orator

The Hampden crews made a long and dangerous flight from bases in Scotland (4–5 September) and assembled at Vaenga airfield on the Kola Inlet, 25 mi (40 km) north of Murmansk.

Operation Orator had deterred the Germans from risking their capital ships against PQ 18 and after converting the Soviet Air Forces (VVS) to the Hampden and Spitfire aircraft to be left behind, the aircrew and ground personnel returned to Britain.

During the lull, Admiral John "Jack" Tovey concluded that the Home Fleet had been of no great protection to convoys once beyond Bear Island, midway between Svalbard and the North Cape of Norway.

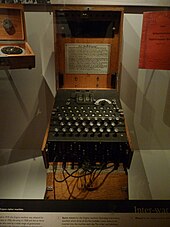

[5] The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) based at Bletchley Park housed a small industry of code-breakers and traffic analysts.

In 1941, B-Dienst read signals from the Commander in Chief Western Approaches informing convoys of areas patrolled by U-boats, enabling the submarines to move into "safe" zones.

[9] In early September, Finnish Radio Intelligence deciphered a Soviet Air Force transmission which divulged the convoy itinerary and forwarded it to the Germans.

The ships were still vulnerable while unloading at Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Polyarny and Hawker Hurricane fighters delivered by the first Arctic convoy, were intended for air defence against the Luftwaffe.

In Operation Dervish (21–31 August 1941), six elderly freighters sailed from Iceland for Archangelsk carrying wood, rubber, tin and fifteen crated Hawker Hurricane fighters.

In Operation Strength, the aircraft carrier HMS Argus carried 24 Hurricanes concurrent with the convoy, escorted by three cruisers with the RAF ground party.

B-Dienst signals interception and documents recovered from the crashed Hampden UB-C, revealed the crossover and escort changeover points of convoys PQ 18 and QP 14 and other details including Operation Orator.

[25] A Search & Strike Force (S&SF), commanded by Group Captain Frank Hopps, was to fly to north Russia and operate over the Barents Sea.

There was no time to fit long-range fuel tanks and each Hampden was to carry a member of the ground staff, the rest travelling to Murmansk on Tuscaloosa, with the Mk XII torpedoes, munitions and other stores.

A direct route over the mountains of Norway would be only 1,100 nmi (1,300 mi; 2,000 km) long but the fuel consumed in climbing high enough would leave little left to overcome head winds, engine trouble, navigation errors or a landing delay.

AT109 ("UB-C") of 455 Squadron, piloted by Sqn Ldr James Catanach, landed on a beach in northern Norway after being damaged by flak from a German submarine chaser and the crew were taken prisoner.

One pilot made a wheels-up landing in soft ground at Khibiniy, several miles north of Afrikanda and the other Hampden was written off after hitting tree stumps.

Forced to ditch in a lake, the crew were strafed in the water and the ventral gunner, Sgt Walter Tabor (RCAF) died, either from bullet wounds or drowning when the aircraft sank.

[46] Soon after midnight on 10/11 September, the Admiralty supplied Enigma messages to the British escort commander that Admiral Hipper was due at Altafjord at 3:00 a.m. and in the afternoon reported that Tirpitz was still at Narvik.

Detailed information on German intentions was provided by Allied code breakers, through Ultra signals decrypts and eavesdropping on Luftwaffe wireless communications.

The escort ships and the aircraft of Avenger were able to use signals intelligence from the Admiralty to provide early warning of some air attacks and to attempt evasive routeing of the convoy around concentrations of U-boats.

The Catalina detachment based in Russia carried overload tanks instead of depth charges and could only menace the U-boats and report their positions to Allied naval ships.

The main task of the Catalinas was to maintain ten crossover patrols, AA to KK, 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) from the Norwegian coast, from west of Narvik to east of the North Cape.

As PQ 18 sailed around Norway, the patrol areas moved north-eastwards; AA to CC were flown by the Catalinas from Shetland, as were DD to EE but the aircraft flew on to Russia.

From above, the Arctic tundra looked uninviting but having landed, the crews found the Soviet Naval Aviation (Morskaya Aviatsiya) base at Lake Lakhta an idyllic setting, lying amidst woods and cliffs.

The flight from Lake Lakhta to Grasnaya took about five hours and once over PQ 18, the Catalina would circle it, keeping a careful watch on aircraft nearby in case of mistaken identity.

[52] The PR Spitfires at Vayenga had their RAF roundels painted out and replaced by red stars: oblique F 24 cameras were used on twelve sorties to Narvik and Altafjord, flying through foul weather to keep watch over the German ships.

[51] On the night of 13/14 September, communications between PQ 18 and Lake Lakhta failed, a Catalina at Grasnaya was unable to take off until dawn and the PR sortie found Altafjord covered by cloud.

[53] Each aircraft carried an 18 inch Mark XII torpedo and the force flew to the maximum distance that Tirpitz could have reached then turned to follow the track back to Altafjord, as far as the Catalina patrol zone.

The pilot of a VVS Yak fighter, who had dived on the Ju 88s from approximately 9,000 ft (2,700 m), was forced to bail out when the tail of his aircraft was shot off by Soviet anti-aircraft fire.

[59][60][17] In the 2005 edition of Arctic Airmen... Ernest Schofield and Roy Nesbit wrote that "it is reasonable to assume that the aircraft based in north Russia had worried the German commander".

[51] The RAF agreed to donate the Hampdens and PR Spitfires to the VVS; S&SF personnel were to return to Britain by sea after helping to convert the Soviet air- and ground-crews to both types.