Operation Varsity

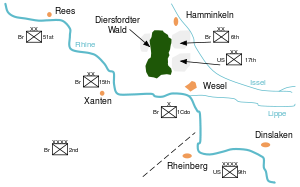

Varsity was meant to help the surface river assault troops secure a foothold across the Rhine in Western Germany by landing two airborne divisions on its eastern bank near the village of Hamminkeln and the town of Wesel.

Still, the operation was a success: both divisions captured Rhine bridges and secured towns that could have been used by Germany to delay the advance of the British ground forces.

However, the U.S. 17th Airborne Division, under Major General William Miley, had been activated only in April 1943 and had arrived in Britain in August 1944, too late to participate in Operation Overlord.

[16] Operation Varsity was planned with these three airborne divisions in mind, with all three to be dropped behind German lines in support of the 21st Army Group as it conducted its amphibious assaults to breach the Rhine.

[18] "To disrupt the hostile defence of the RHINE in the WESEL sector by the seizure of key terrain by airborne attack, in order [...] to facilitate the further offensive operations of the SECOND ARMY."

[20] Unlike Market Garden, the airborne forces would be dropped only a relatively short distance behind German lines, thereby ensuring that reinforcements in the form of Allied ground forces would be able to link up with them within a short period: this avoided risking the same type of disaster that had befallen the British 1st Airborne Division when it had been isolated and practically annihilated by German infantry and armour at Arnhem.

[3] The seven divisions that formed the 1st Parachute Army were short of manpower and munitions, and although farms and villages were well prepared for defensive purposes, there were few mobile reserves, ensuring that the defenders had little way to concentrate their forces against the Allied bridgehead when the assault began.

[28] The mobile reserves that the Germans did possess consisted of some 150 armoured fighting vehicles under the command of 1st Parachute Army, the majority of which belonged to XLVII Panzer Corps.

[29] The situation of the German defenders, and their ability to counter any assault effectively, was worsened when the Allies launched a large-scale air attack one week prior to Operation Varsity.

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion lost its Commanding Officer (CO), Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Nicklin, to German small-arms fire only moments after he landed.

[32] Canadian medical orderly Corporal Frederick George Topham was awarded the Victoria Cross for his efforts to recover casualties and take them for treatment, despite his own wounds and great personal danger.

The drop zone came under heavy fire from German troops stationed nearby, and was subjected to shellfire and mortaring which inflicted casualties in the battalion rendezvous areas.

[38] The brigade was then ordered to move due east and clear an area near Schermbeck, as well as to engage German forces gathered to the west of the farmhouse where the 6th Airborne Division Headquarters was established.

[38] However, the majority of the gliders survived, allowing the battalions of the brigade to secure intact the three bridges over the River Issel that they had been tasked with capturing, as well as the village of Hamminkeln with the aid of American paratroopers of the 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which had been dropped by mistake nearby.

[42] The actions of the 507th Parachute Infantry during the initial landing also gained the division its second Medal of Honor, when Private George Peters posthumously received the award after charging a German machine gun nest and eliminating it with rifle fire and grenades, allowing his fellow paratroopers to gather their equipment and capture the regiment's first objective.

[45] Despite this inaccuracy the paratroopers swiftly rallied and aided the British glider-borne troops who were landing simultaneously, eliminating several German artillery batteries that were covering the area.

[46] By 2 pm, Colonel Coutts reported to Divisional Headquarters that the 513th Parachute Infantry had secured all of its objectives, having knocked out two tanks and two complete regiments of artillery during their assault.

[46] During its attempts to secure its objectives, the regiment also gained a third Medal of Honor for the 17th Airborne Division when Private First Class Stuart Stryker posthumously received the award after leading a charge against a German machine-gun nest, creating a distraction to allow the rest of his platoon to capture the fortified position in which the machine-gun was situated.

[43] The third component of the 17th Airborne Division to take part in the operation was the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR), under the command of Colonel James Pierce.

By 27 March, twelve bridges suitable for heavy armour had been installed over the Rhine and the Allies had 14 divisions on the east bank of the river, penetrating up to 10 miles (16 km).

[50] The U.S. 17th Airborne Division gained its fourth Medal of Honor in the days following the operation, when Technical Sergeant Clinton M. Hedrick of the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment received the award posthumously after aiding in the capture of Lembeck Castle, which had been turned into a fortified position by the Germans.

[59] Historian Peter Allen states that while the airborne forces took heavy casualties, Varsity diverted German attention from the Rhine crossing onto themselves.

[55] In The Last Offensive the US Army official history by Charles B. MacDonald (1990) he asked whether under the prevailing circumstances an airborne attack (was) necessary or .. even justified.

[16] Thus, the unsolved problem of a shortage of transport aircraft meant that a third of the planned troops to be used were discarded, weakening the fighting power of the airborne formation.

[59] There was also a shortage of gliders, although Brereton eventually got the 906 CG-4As he needed for Varsity and 926 for Operation Choker II, an American crossing of the Rhine at Worms planned for March.

[64] Some historians have commented on this failure; Gerard Devlin argues that because of this lack of aircraft the remaining two divisions were forced to shoulder the operation by themselves.

The airborne landings were conducted during the day primarily because the planners believed that a daytime operation had a better chance of success than at night, the troops being less scattered.

Finally, while many if not all of the C-47s used in Operation Varsity had been retrofitted with self-sealing fuel tanks,[67] the much larger C-46 Commando aircraft employed in the drop received no such modification.

[70] Lieutenant-Colonel Otway, who wrote an official history of the British airborne forces during World War II, stated that Operation Varsity highlighted the vulnerability of glider-borne units.

While they arrived in complete sub-units and were able to move off more quickly than airborne troops dropped by parachute, the gliders were easy targets for anti-aircraft fire and short-range small-arms fire once landed; Otway concluded that in any future operations, troops dropped by parachute should secure landing zones prior to the arrival of glider-borne units.