Optical coating

The simplest optical coatings are thin layers of metals, such as aluminium, which are deposited on glass substrates to make mirror surfaces, a process known as silvering.

By controlling the thickness and density of metal coatings, it is possible to decrease the reflectivity and increase the transmission of the surface, resulting in a half-silvered mirror.

By careful choice of the exact composition, thickness, and number of these layers, it is possible to tailor the reflectivity and transmitivity of the coating to produce almost any desired characteristic.

Alternatively, the coating can be designed such that the mirror reflects light only in a narrow band of wavelengths, producing an optical filter.

The optimum refractive indices for multiple coating layers at angles of incidence other than 0° is given by Moreno et al.

In practice, the performance of a simple one-layer interference coating is limited by the fact that the reflections only exactly cancel for one wavelength of light at one angle, and by difficulties finding suitable materials.

Magnesium fluoride (MgF2) is often used, since it is hard-wearing and can be easily applied to substrates using physical vapour deposition, even though its index is higher than desirable (n=1.38).

With such coatings, reflection as low as 1% can be achieved on common glass, and better results can be obtained on higher index media.

Further reduction is possible by using multiple coating layers, designed such that reflections from the surfaces undergo maximum destructive interference.

By using two or more layers, broadband antireflection coatings which cover the visible range (400-700 nm) with maximum reflectivities of less than 0.5% are commonly achievable.

This periodic system significantly enhances the reflectivity of the surface in the certain wavelength range called band-stop, whose width is determined by the ratio of the two used indices only (for quarter-wave systems), while the maximum reflectivity increases up to almost 100% with a number of layers in the stack.

The best of these coatings built-up from deposited dielectric lossless materials on perfectly smooth surfaces can reach reflectivities greater than 99.999% (over a fairly narrow range of wavelengths).

Telescopes such as TRACE or EIT that form images with EUV light use multilayer mirrors that are constructed of hundreds of alternating layers of a high-mass metal such as molybdenum or tungsten, and a low-mass spacer such as silicon, vacuum deposited onto a substrate such as glass.

Using multilayer optics it is possible to reflect up to 70% of incident EUV light (at a particular wavelength chosen when the mirror is constructed).

Transparent conductive coatings are also used extensively to provide electrodes in situations where light is required to pass, for example in flat panel display technologies and in many photoelectrochemical experiments.

These are known as RAITs (Radar Attenuating / Infrared Transmitting) and include materials such as boron doped DLC (Diamond-like carbon)[citation needed].

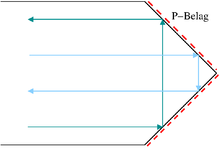

The multiple internal reflections in roof prisms cause a polarization-dependent phase-lag of the transmitted light, in a manner similar to a Fresnel rhomb.

This must be suppressed by multilayer phase-correction coatings applied to one of the roof surfaces to avoid unwanted interference effects and a loss of contrast in the image.

[7] From a technical point of view, the phase-correction coating layer does not correct the actual phase shift, but rather the partial polarization of the light that results from total reflection.

FROCs were used as both monolithic spectrum splitters and selective solar absorbers, which makes them suitable for hybrid solar-thermal energy generation.

[10] They can be designed to reflect specific wavelength ranges, aligning with the energy band gap of photovoltaic cells, while absorbing the remaining solar spectrum.

Additionally, their low infrared emissivity minimizes thermal losses, increasing the system's overall optothermal efficiency.