Optogenetics

[1] In systems neuroscience, the ability to control the activity of a genetically defined set of neurons has been used to understand their contribution to decision making,[2] learning,[3] fear memory,[4] mating,[5] addiction,[6] feeding,[7] and locomotion.

[27] Peter Hegemann, studying the light response of green algae at the University of Regensburg, had discovered photocurrents that were too fast to be explained by the classic g-protein-coupled animal rhodopsins.

[28] Teaming up with the electrophysiologist Georg Nagel at the Max Planck Institute in Frankfurt, they could demonstrate that a single gene from the alga Chlamydomonas produced large photocurrents when expressed in the oocyte of a frog.

Karl Deisseroth in the Bioengineering Department at Stanford published the notebook pages from early July 2004 of his initial experiment showing light activation of neurons expressing a channelrhodopsin.

[27] Zhuo-Hua Pan of Wayne State University, researching on restore sight to blindness, tried channelrhodopsin out in ganglion cells—the neurons in human eyes that connect directly to the brain.

[36] The groups of Alexander Gottschalk and Georg Nagel made the first ChR2 mutant (H134R) and were first to use channelrhodopsin-2 for controlling neuronal activity in an intact animal, showing that motor patterns in the roundworm C. elegans could be evoked by light stimulation of genetically selected neural circuits (published in December 2005).

[37] In mice, controlled expression of optogenetic tools is often achieved with cell-type-specific Cre/loxP methods developed for neuroscience by Joe Z. Tsien back in the 1990s[38] to activate or inhibit specific brain regions and cell-types in vivo.

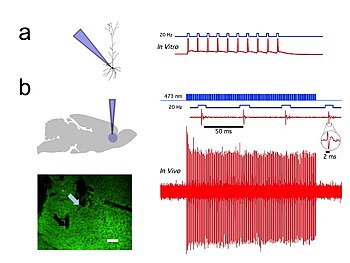

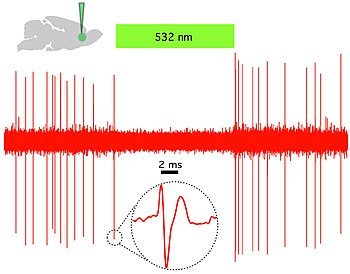

[43] Optogenetics provides millisecond-scale temporal precision which allows the experimenter to keep pace with fast biological information processing (for example, in probing the causal role of specific action potential patterns in defined neurons).

Indeed, to probe the neural code, optogenetics by definition must operate on the millisecond timescale to allow addition or deletion of precise activity patterns within specific cells in the brains of intact animals, including mammals (see Figure 1).

Additionally, beyond its scientific impact optogenetics represents an important case study in the value of both ecological conservation (as many of the key tools of optogenetics arise from microbial organisms occupying specialized environmental niches), and in the importance of pure basic science as these opsins were studied over decades for their own sake by biophysicists and microbiologists, without involving consideration of their potential value in delivering insights into neuroscience and neuropsychiatric disease.

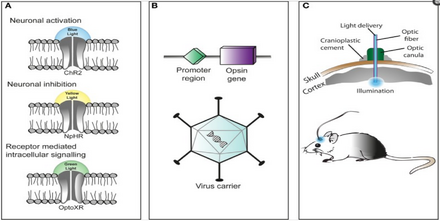

Building on prior work fusing vertebrate opsins to specific G-protein coupled receptors[53] a family of chimeric single-component optogenetic tools was created that allowed researchers to manipulate within behaving mammals the concentration of defined intracellular messengers such as cAMP and IP3 in targeted cells.

[54] Other biochemical approaches to optogenetics (crucially, with tools that displayed low activity in the dark) followed soon thereafter, when optical control over small GTPases and adenylyl cyclase was achieved in cultured cells using novel strategies from several different laboratories.

A popular approach is to introduce an engineered viral vector that contains the optogenetic actuator gene attached to a specific promoter such as CAMKIIα, which is active in excitatory neurons.

By introducing an engineered viral vector containing the optogenetic actuator gene in between two lox-P sites, only the cells producing Cre recombinase will express the microbial opsin.

Recent advances include the advent of wireless head-mounted devices that apply LEDs to the targeted areas and as a result, give the animals more freedom to move.

[51][76] Restricting the opsin to specific regions of the plasma membrane such as dendrites, somata or axon terminals provides a more robust understanding of neuronal circuitry.

[76] This spectral overlap makes it very difficult to combine opsin activation with genetically encoded indicators (GEVIs, GECIs, GluSnFR, synapto-pHluorin), most of which need blue light excitation.

The field of optogenetics has furthered the fundamental scientific understanding of how specific cell types contribute to the function of biological tissues such as neural circuits in vivo.

On the clinical side, optogenetics-driven research has led to insights into restoring with light[1],[83] Parkinson's disease[84][85] and other neurological and psychiatric disorders such as autism, Schizophrenia, drug abuse, anxiety, and depression.

[90][91][92][93] One such example of a neural circuit is the connection made from the basolateral amygdala to the dorsal-medial prefrontal cortex where neuronal oscillations of 4 Hz have been observed in correlation to fear induced freezing behaviors in mice.

Transgenic mice were introduced with channelrhodoposin-2 attached with a parvalbumin-Cre promoter that selectively infected interneurons located both in the basolateral amygdala and the dorsal-medial prefrontal cortex responsible for the 4 Hz oscillations.

[97] Optogenetics, freely moving mammalian behavior, in vivo electrophysiology, and slice physiology have been integrated to probe the cholinergic interneurons of the nucleus accumbens by direct excitation or inhibition.

The few cholinergic neurons present in the nucleus accumbens may prove viable targets for pharmacotherapy in the treatment of cocaine dependence[52] In vivo and in vitro recordings from the University of Colorado, Boulder Optophysiology Laboratory of Donald C. Cooper Ph.D. showing individual CAMKII AAV-ChR2 expressing pyramidal neurons within the prefrontal cortex that demonstrated high fidelity action potential output with short pulses of blue light at 20 Hz (Figure 1).

Additionally, using engineered red-shifted channels as f-Chrimson allow for stimulation using longer wavelengths, which decreases the potential risks of phototoxicity in the long term without compromising gating speed.

[110] Optogenetic stimulation of a modified red-light excitable channelrhodopsin (ReaChR) expressed in the facial motor nucleus enabled minimally invasive activation of motoneurons effective in driving whisker movements in mice.

The currently available optogenetic actuators allow for the accurate temporal control of the required intervention (i.e. inhibition or excitation of the target neurons) with precision routinely going down to the millisecond level.

[124][125] This kind of approach has already been used in several brain regions: Sharp waves and ripple complexes (SWRs) are distinct high frequency oscillatory events in the hippocampus thought to play a role in memory formation and consolidation.

[1] This study anticipated aspects of the later development of optogenetics in the brain, for example, by suggesting that "Directed light delivery by fiber optics has the potential to target selected cells or tissues, even within larger, more-opaque organisms.

[150] In addition, a rapid negative feedback loop in the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway was discovered using pulsatile activation of a photoswitchable RAF engineered with photodissociable Dronpa domains.

"[163] In 2019, Bamberg, Boyden, Deisseroth, Hegemann, Miesenböck and Georg Nagel were awarded the Rumford Prize by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in recognition of "their extraordinary contributions related to the invention and refinement of optogenetics.