Orchestration

In jazz big bands, the composer or songwriter may write a lead sheet, which contains the melody and the chords, and then one or more orchestrators or arrangers may "flesh out" these basic musical ideas by creating parts for the saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and the rhythm section (bass, piano/jazz guitar/Hammond organ, drums).

Sometimes, for a forceful effect, a composer will indicate in the score that all of the strings (violins, violas, cellos, and double basses) will play the melody in unison, at the same time.

For example, in the late 20th century and onwards, an orchestrator could have a melody played by the first violins doubled by a futuristic-sounding synthesizer or a theremin to create an unusual effect.

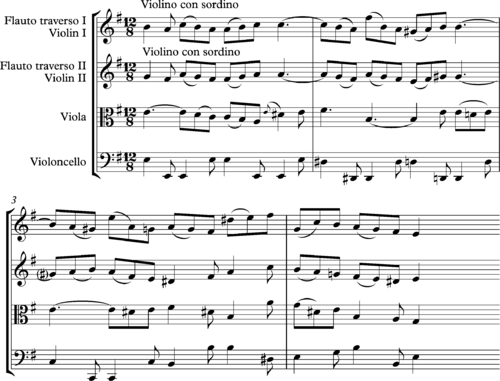

The orchestral accompaniment to the aria 'et misericordia' from J. S. Bach's Magnificat, BWV 243 (1723) features muted strings doubled by flutes, a subtle combination of mellow instrumental timbres.

A particularly imaginative example of Bach's use of changing instrumental colour between orchestral groups can be found in his Cantata BWV 67, Halt im Gedächtnis Jesum Christ.

In the dramatic fourth movement, Jesus is depicted as quelling his disciples' anxiety (illustrated by agitated strings) by uttering Friede sei mit euch ("Peace be unto you").

The strings dovetail with sustained chords on woodwind to accompany the solo singer, an effect John Eliot Gardiner likens to "a cinematic dissolve.

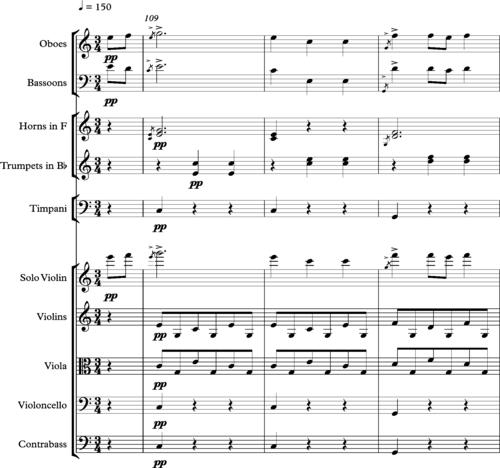

Within a space of eight bars, we hear recorders, oboes da caccia, horns and strings creating a "glittery sheen" of contrasted timbres, sonorities and textures ranging from just two horns against a string pedal point in the first bar to a "restatement of the octave unison theme, this time by all the voices and instruments spread over five octaves" in bars 7-8:[6]In contrast, Bach's deployment of his instrumental forces in the opening movement of his St John Passion evokes a much darker drama: “The relentless tremulant pulsation generated by the reiterated bass line, the persistent sighing figure in the violas and the violins the swirling motion in the violins so suggestive of turmoil… all contribute to its unique pathos.

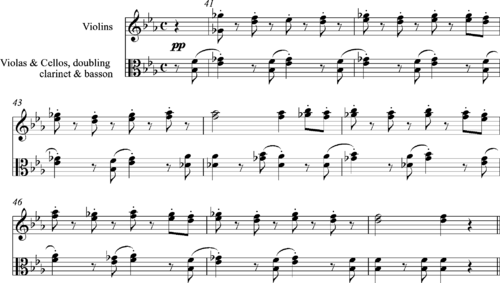

"[9] In 'The Entrance of Polymnie' from his opera Les Boréades (1763), the predominant string texture is shot through with descending scale figures on the bassoon, creating an exquisite blend of timbres:In the aria 'Rossignols amoureux' from his opera Hippolyte et Aricie, Rameau evokes the sound of lovelorn nightingales by means of two flutes blending with a solo violin, while the rest of the violins play sustained notes in the background.

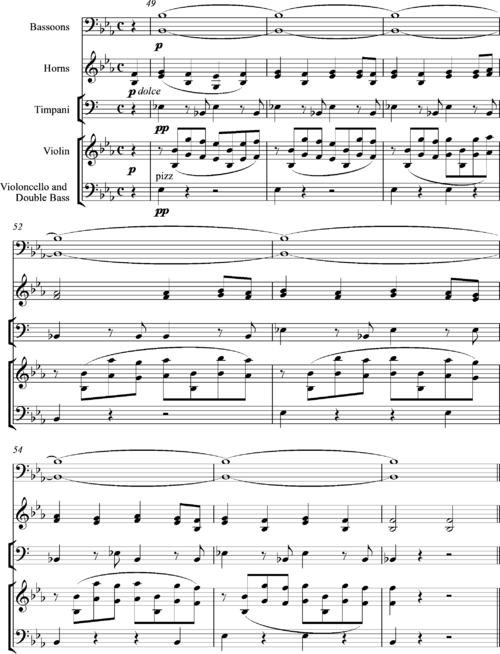

The oom-pah-pah of a German dance band is rendered with the utmost refinement, amazingly by kettledrums and trumpets pianissimo, and the rustic glissando… is given a finicky elegance by the grace notes in the horns as well as by the doubling of the melody an octave higher with the solo violin.

"[10] Another example of Haydn's imagination and ingenuity that shows how well he understood how orchestration can support harmony may be found in the concluding bars of the second movement of his Symphony No.

The first and second violins weave curly parallel melodic lines, a tenth apart, underpinned by a pedal point in the double basses and a sustained octave in the horns.

In 1792, an early listener marvelled at the dazzling orchestration of this movement "ineffably grand and rich in ideas, with striking variety in almost all obbligato parts.

Beethoven's innovative mastery of orchestration and his awareness of the effect of highlighting, contrasting and blending distinct instrumental colours are well exemplified in the Scherzo of his Symphony No.

"[21] Another demonstration of Beethoven's consummate skill at obtaining the maximum variety out of seemingly unprepossessing and fairly simple material can be found in the first movement of the Piano Concerto No.

[24] : The minor version of the theme also appears in the cadenza, played staccato by the solo piano: This is followed, finally, by a restatement of the major key version, featuring horns playing legato, accompanied by pizzicato strings and filigree arpeggio figuration in the solo piano: Fiske (1970) says that Beethoven shows "a superb flood of invention" through these varied treatments.

A particularly spectacular instance is the "Queen Mab" scherzo from the Romeo et Juliette symphony, which Hugh Macdonald (1969, p51) describes as "Berlioz's supreme exercise in light orchestral texture, a brilliant, gossamer fabric, prestissimo and pianissimo almost without pause: Boulez points out that the very fast tempo must have made unprecedented demands on conductors and orchestras of the time (1830), "Because of the rapid and precise rhythms, the staccatos which must be even and regular in all registers, because of the isolated notes that occur right at the end of the bar on the third quaver…all of which must fall into place with absolutely perfect precision.

"[31] Peter Latham says that Wagner had a "unique appreciation of the possibilities for colour inherent in the instruments at his disposal, and it was this that guided him both in his selection of new recruits for the orchestral family and in his treatment of its established members.

The well-known division of that family into strings, woodwind, and brass, with percussion as required, he inherited from the great classical symphonists such changes as he made were in the direction of splitting up these groups still further."

Latham gives as an example, the sonority of the opening of the opera Lohengrin, where "the ethereal quality of the music" is due to the violins being "divided up into four, five, or even eight parts instead of the customary two.

"[35] For example, in the evocative "Fire Music" that concludes Die Walküre, "the multiple arpeggiations of the wind chords and the contrary motion in the strings create an oscillation of tone-colours almost literally matching the visual flickering of the flames.

The full novelty of this colour change with the oboe, both as intensity and as timbre, can be appreciated only after the theme is repeated in harmony and in one of the most gorgeous orchestrations of even Wagner's Technicolor imagination.

Later, during the opening scene of the first act of Parsifal, Wagner offsets the bold brass with gentler strings, showing that the same musical material feels very different when passed between contrasting families of instruments: On the other hand, the prelude to the opera Tristan and Isolde exemplifies the variety that Wagner could extract through combining instruments from different orchestral families with his precise markings of dynamics and articulation.

"[40] According to Roger Scruton, "Seldom since Bach's inspired use of obbligato parts in his cantatas have the instruments of the orchestra been so meticulously and lovingly adapted to their expressive role by Wagner in his later operas.

Apart from the early impact of Wagner, Debussy was also fascinated by music from Asia that according to Austin "he heard repeatedly and admired intensely at the Paris World exhibition of 1889".

Wagner's influence can be heard in the strategic use of silence, the sensitively differentiated orchestration and, above all in the striking half-diminished seventh chord spread between oboes and clarinets, reinforced by a glissando on the harp.

"[48][49] Later in the Faune, Debussy builds a complex texture, where, as Austin says, "Polyphony and orchestration overlap...He adds to all the devices of Mozart, Weber, Berlioz and Wagner the possibilities that he learned from the heterophonic music of the Far East....

While working on the piano score, Debussy wrote: 'I am thinking of that orchestral colour which seems to be illuminated from behind, and for which there are such marvellous displays in Parsifal' The idea, then, was to produce timbre without glare, subdued... but to do so with clarity and precision.

Some staff composers at the Walt Disney studios during the 1930s and 1940s (except for Frank Churchill) had orchestrated their own music, such as Paul J. Smith (on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, The Three Caballeros, and Fun and Fancy Free.

Robert Russell Bennett (George Gershwin, Rodgers and Hammerstein) was one of America's most prolific orchestrators (particularly of Broadway shows) of the 20th century, sometimes scoring over 80 pages a day.