Oregon Country

Article III of the 1818 treaty gave joint control to both nations for ten years, allowed land to be claimed, and guaranteed free navigation to all mercantile trade.

Its coastal areas north of the Columbia River were frequented by ships from all nations engaged in the maritime fur trade, with many vessels between the 1790s and 1810s coming from Boston.

The Hudson's Bay Company, whose Columbia Department comprised most of the Oregon Country and north into New Caledonia and beyond 54°40′ N, with operations reaching tributaries of the Yukon River, managed and represented British interests in the region.

[4] This was the last period in which the Oregon Country's Indian nations retained a sizeable majority in their land, prior to the rapid and devastating arrival of European diseases in the 1860s, and were able to maintain relative economic independence thanks to the necessity of their hunting skills in the fur trade.

The term orejón comes from the historical chronicle Relación de la Alta y Baja California (1598)[6] which was written by the New Spaniard Rodrigo Motezuma and which made reference to the Columbia River when the Spanish explorers penetrated into the North American territory that became part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

It is most probable that the American territory was named by the Spaniards, as there are some populations in Spain such as Arroyo del Oregón, which is in the province of Ciudad Real, also considering that the individualization in Spanish language el Orejón with the mutation of the letter g instead of j.

He erected a pole and a notice claiming the country for the United Kingdom and stating the intention of the North West Company to build a trading post on the site.

Later in 1811, on the same expedition, he finished his survey of the entire Columbia, arriving at a partially constructed Fort Astoria two months after the departure of John Jacob Astor's ill-fated Tonquin.

The United States based its claim in part on Robert Gray's entry of the Columbia River in 1792 and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

It asserted its ownership of the region north of the 51st parallel by the Ukase of 1821, which was quickly challenged by the other powers and withdrawn to 54°40′N by separate treaties with the U.S. and Britain in 1824 and 1825, respectively.

[17] Meanwhile, the United States and Britain negotiated the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, which extended the boundary between their territories west along the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains.

Along the way, Thompson had set foot on and claimed for the British Crown the lands near the future Fort Nez Percés site at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers.

These were difficult to obtain in the Oregon Country because of the Hudson's Bay Company policy of creating a "fur desert": deliberate over-hunting of the area's frontiers so that American trades would find nothing there.

[23] The mountain men, like the Metis employees of the Canadian fur companies, adopted Indian ways, and many of them married Native American women.

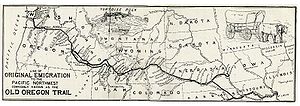

American settlers began to arrive from the east via the Oregon Trail starting in the early 1840s and came in increasing numbers each subsequent year.

The Hudson's Bay Company, which had previously discouraged settlement as it conflicted with the lucrative fur trade, belatedly reversed its position.

In 1841, on orders from Sir George Simpson, James Sinclair guided more than 100 settlers from the Red River Colony to settle on HBC farms near Fort Vancouver.

It was seen as significant that the expansions be parallel, as the relative proximity to other states and territories made it appear likely that Texas would be pro-slavery and Oregon against slavery.

Polk's uncompromising support for expansion into Texas and relative silence on the Oregon boundary dispute led to the phrase "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!"

McLoughlin had devoted his life's work to the Columbia business, and his personal interests were increasingly linked to the growing settlements in the Willamette Valley.

A general HBC shift toward Pacific shipping and away from the interior of the continent made Victoria Harbour much more suitable than Fort Vancouver's location on the Columbia River.

The growing numbers of American settlers along the lower Columbia gave Simpson reason to question the long-term security of Fort Vancouver.

By 1842, he thought it more likely that the United States would at least demand Puget Sound, and the British government would accept a border as far north as the 49th parallel, excluding Vancouver Island.

[30] Alexander Ross, an early Scottish Canadian fur trader, describes the lower reaches of the Willamette River, in the south of the Oregon Country (known to him as the Columbia District): The banks of the river throughout are low and skirted in the distance by a chain of moderately high lands on each side, interspersed here and there with clumps of wide spreading oaks, groves of pine, and a variety of other kinds of woods.

After living in Oregon from 1843 to 1848, Peter H. Burnett wrote: [Oregonians] were all honest, because there was nothing to steal; they were all sober, because there was no liquor to drink; there were no misers, because there was no money to hoard; and they were all industrious, because it was work or starve.