Oromo language

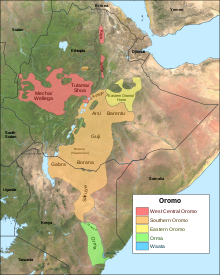

It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa.

[15] Forms of Oromo are spoken as a first language by an additional half-million people in parts of northern and eastern Kenya.

[16] It is also spoken by smaller numbers of emigrants in other African countries such as South Africa, Libya, Egypt and Sudan.

[17] Oromo serves as one of the official working languages of Ethiopia[4] and is also the working language of several of the states within the Ethiopian federal system including Oromia,[14] Harari and Dire Dawa regional states and of the Oromia Zone in the Amhara Region.

[25] In Kenya, the Ethnologue also lists 627,000 speakers of Borana and Orma, two languages closely related to Ethiopian Oromo.

In 1842, Johann Ludwig Krapf began translations of the Gospels of John and Matthew into Oromo, as well as a first grammar and vocabulary.

[29] After Abyssinia annexed Oromo's territory, the language's development into a full-fledged writing instrument was interrupted.

The few works that had been published, most notably Onesimos Nesib's and Aster Ganno's translations of the Bible from the late 19th century, were written in the Ge'ez alphabet.

All Oromo materials printed in Ethiopia at that time, such as the newspaper Bariisaa, Urjii and many others, were written in the traditional Ethiopic script.

To combat Somali wide-reaching influence, the Ethiopian Government initiated an Oromo language program radio of their own.

[32] The Borana Bible in Kenya was printed in 1995 using the Latin alphabet, but not using the same spelling rules as in Ethiopian Qubee.

The first comprehensive online Oromo dictionary was developed by the Jimma Times Oromiffa Group (JTOG) in cooperation with SelamSoft.

[35] With the adoption of Qubee, it is believed more texts were written in the Oromo language between 1991 and 1997 than in the previous 100 years.

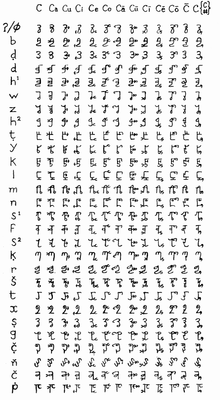

Despite structural and organizational influences from Ge'ez and the Arabic script, it is a graphically independent creation designed specifically for Oromo phonology.

Like most other Ethiopian languages, whether Semitic, Cushitic, or Omotic, Oromo has a set of ejective consonants, that is, voiceless stops or affricates that are accompanied by glottalization and an explosive burst of air.

Oromo has another glottalized phone that is more unusual, an implosive retroflex stop, "dh" in Oromo orthography, a sound that is like an English "d" produced with the tongue curled back slightly and with the air drawn in so that a glottal stop is heard before the following vowel begins.

In the Qubee alphabet, letters include the digraphs[40] ch, dh, ny, ph, sh.

In the charts below, the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol for a phoneme is shown in brackets where it differs from the Oromo letter.

[44] Similar to most other Afroasiatic languages, Oromo has two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine, and all nouns belong to either one or the other.

Among the other common plural suffixes are -(w)wan, -een, and -(a)an; the latter two may cause a preceding consonant to be doubled: waggaa 'year', waggaawwan 'years', laga 'river', laggeen 'rivers', ilma 'son', ilmaan 'sons'.

Vowel endings of nouns are dropped before these suffixes: karaa 'road', karicha 'the road', nama 'man', namicha/namticha 'the man', haroo 'lake', harittii 'the lake'.

The Oromo word that translates 'we' does not appear in this sentence, though the person and number are marked on the verb dhufne ('we came') by the suffix -ne.

When the subject in such sentences needs to be given prominence for some reason, an independent pronoun can be used: 'nuti kaleessa dhufne' 'we came yesterday'.

In most dialects there is a distinction between masculine and feminine possessive adjectives for first and second person (the form agreeing with the gender of the modified noun).

As in languages such as French, Russian, and Turkish, the Oromo second person plural is also used as a polite singular form, for reference to people that the speaker wishes to show respect towards.

Like English, Oromo makes a two-way distinction between proximal ('this, these') and distal ('that, those') demonstrative pronouns and adjectives.

For example, in dhufne 'we came', dhuf- is the stem ('come') and -ne indicates that the tense is past and that the subject of the verb is first person plural.

As in many other Afroasiatic languages, Oromo makes a basic two-way distinction in its verb system between the two tensed forms, past (or "perfect") and present (or "imperfect" or "non-past").

The negative particle hin, shown as a separate word in the table, is sometimes written as a prefix on the verb.

The common verbs fedh- 'want' and godh- 'do' deviate from the basic conjugation pattern in that long vowels replace the geminated consonants that would result when suffixes beginning with t or n are added: fedha 'he wants', feeta 'you (sg.)