Orpheus

He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece,[6] and even descended into the underworld of Hades, to recover his lost wife Eurydice.

[17] The earliest literary reference to Orpheus is a two-word fragment of the 6th century BC lyric poet Ibycus: onomaklyton Orphēn ('Orpheus famous-of-name').

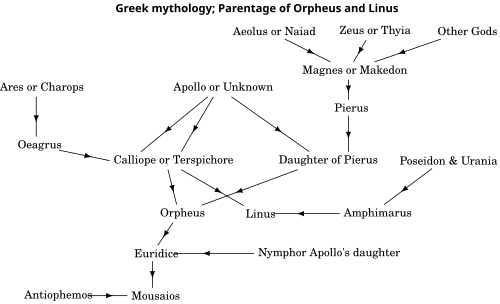

[19][20] Pindar calls Orpheus 'the father of songs'[21] and identifies him as a son of the Thracian mythological king Oeagrus[22] and the Muse Calliope.

Poets such as Simonides of Ceos said that Orpheus's music and singing could charm the birds, fish and wild beasts, coax the trees and rocks into dance,[24] and divert the course of rivers.

Orpheus was an augur and seer; he practiced magical arts and astrology, founded cults to Apollo and Dionysus,[27] and prescribed the mystery rites preserved in Orphic texts.

He made money as a musician and "wizard" – Strabo uses αγυρτεύοντα (agurteúonta),[32] also used by Sophocles in Oedipus Tyrannus to characterize Tiresias as a trickster with an excessive desire for possessions.

[34][non-primary source needed] "Orpheus ... is repeatedly referred to by Euripides, in whom we find the first allusion to the connection of Orpheus with Dionysus and the infernal regions: he speaks of him as related to the Muses (Rhesus 944, 946); mentions the power of his song over rocks, trees, and wild beasts (Medea 543, Iphigenia in Aulis 1211, Bacchae 561, and a jocular allusion in Cyclops 646); refers to his charming the infernal powers (Alcestis 357); connects him with Bacchanalian orgies (Hippolytus 953); ascribes to him the origin of sacred mysteries (Rhesus 943), and places the scene of his activity among the forests of Olympus (Bacchae 561.

He wrote Decennalia, and in the opinion of Gyraldlus the Argonautics, which are now extant under the name of Orpheus, with other writings called Orphical, but which according to Cicero some ascribe to Cecrops the Pythagorean.

[39][40] The testimonies referring to his death, grave and heroic worship, for example early attestations to the existence of a real, or fictitious, gravestone epigram of Orpheus, point most strongly to his Macedonian links.

Chiron told Jason that without the aid of Orpheus, the Argonauts would never be able to pass the Sirens—the same Sirens encountered by Odysseus in Homer's epic poem the Odyssey.

His music softened the hearts of Hades and Persephone, who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to earth on one condition: he should walk in front of her and not look back until they both had reached the upper world.

[62] Other ancient writers, however, speak of Orpheus's visit to the underworld in a more negative light; according to Phaedrus in Plato's Symposium,[63] the infernal gods only "presented an apparition" of Eurydice to him.

In fact, Plato's representation of Orpheus is that of a coward, as instead of choosing to die in order to be with the one he loved, he instead mocked the gods by trying to go to Hades to bring her back alive.

Virgil wrote in his poem that Dryads wept from Epirus and Hebrus up to the land of the Getae (north east Danube valley) and even describes him wandering into Hyperborea and Tanais (ancient Greek city in the Don river delta)[65] due to his grief.

[66] The myth theme of not looking back, an essential precaution in Jason's raising of chthonic Brimo Hekate under Medea's guidance,[67] is reflected in the Biblical story of Lot's wife when escaping from Sodom.

According to a Late Antique summary of Aeschylus's lost play Bassarids, Orpheus, towards the end of his life, disdained the worship of all gods except Apollo.

[70]Here his death is analogous with that of Pentheus, who was also torn to pieces by Maenads; and it has been speculated that the Orphic mystery cult regarded Orpheus as a parallel figure to or even an incarnation of Dionysus.

Indeed, he was the first of the Thracian people to transfer his affection to young boys and enjoy their brief springtime, and early flowering this side of manhood.Feeling spurned by Orpheus for taking only male lovers (eromenoi), the Ciconian women, followers of Dionysus,[76] first threw sticks and stones at him as he played, but his music was so beautiful even the rocks and branches refused to hit him.

Euripides in the Hippolytus makes Theseus speak of the "turgid outpourings of many treatises", which have led his son to follow Orpheus and adopt the Bacchic religion.

Alexis, the fourth century comic poet, depicting Linus offering a choice of books to Heracles, mentions "Orpheus, Hesiod, tragedies, Choerilus, Homer, Epicharmus".

In addition to serving as a storehouse of mythological data along the lines of Hesiod's Theogony, Orphic poetry was recited in mystery-rites and purification rituals.

[88] Those who were especially devoted to these rituals and poems often practiced vegetarianism and abstention from sex, and refrained from eating eggs and beans—which came to be known as the Orphikos bios, or "Orphic way of life".

[90] There is also a reference, not mentioning Orpheus by name, in the pseudo-Platonic Axiochus, where it is said that the fate of the soul in Hades is described on certain bronze tablets which two seers had brought to Delos from the land of the Hyperboreans.

A number of Greek religious poems in hexameters were also attributed to Orpheus, as they were to similar miracle-working figures, like Bakis, Musaeus, Abaris, Aristeas, Epimenides, and the Sibyl.

It came therefore to be believed that Orpheus taught, but left no writings, and that the epic poetry attributed to him was written in the sixth century BC by Onomacritus.

By the time when the Orphic writings began to be freely quoted by Christian and Neo-Platonist writers, the theory of the authorship of Onomacritus was accepted by many.

It is believed that in the collection of writings which they used there were several versions, each of which gave a slightly different account of the origin of the universe, of gods and men, and perhaps of the correct way of life, with the rewards and punishments attached thereto.

Poul Anderson's Hugo Award-winning novelette "Goat Song", published in 1972, is a retelling of the story of Orpheus in a science fiction setting.

[93] David Almond's 2014 novel A Song for Ella Grey was inspired by the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, and won the Guardian Children's Fiction Prize in 2015.

Anaïs Mitchell's 2010 folk opera musical Hadestown retells the tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice with a score inspired by American blues and jazz, portraying Hades as the brutal work-boss of an underground mining city.