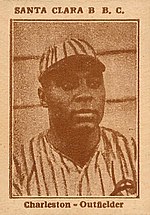

Oscar Charleston

One of the Negro leagues' early stars,[10] Charleston was by 1920 generally considered "the greatest center fielder and one of the most reliable sluggers in black baseball.

He was the second player to win consecutive Triple Crowns in either batting or pitching (after Grover Cleveland Alexander), a feat matched just one time by a batter.

His most productive season was with the St. Louis Giants in 1921, when he hit 15 home runs, 12 triples, and 17 doubles, stole 31 bases, and had a .437 batting average.

In 1945, Charleston became manager of the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers and helped recruit black ballplayers such as Roy Campanella to join the first integrated Major League Baseball teams.

The Hall of Fame website also noted that Charleston had a .326 lifetime batting average in exhibition play against white major leaguers.

[22] After his honorable discharge from the U.S. Army in 1915, Charleston returned to the United States and immediately began his baseball career with the Indianapolis ABCs.

Charleston, called "Charlie" by his teammates, soon moved to the center field position, where he became known for playing shallow (close behind second base) and his one-handed catches.

[27][28] James "Cool Papa" Bell related a story to baseball historian John Holway of another confrontation involving Charleston.

Bell told Holway that around 1935 Charleston tore off the hood of a white-robed Ku Klux Klansman during a trip to Florida.

In 1916 he was a member of the team when it beat the Chicago American Giants to claim what the game's promoters called "The Championship of Colored Baseball."

[31] Charleston remained with the ABCs until 1921, then signed with the Saint Louis Giants, who paid him $400 per month, the league's highest salary.

[32] Charleston's most productive season was with the Saint Louis Giants in 1921, when he hit fifteen home runs, twelve triples, seventeen doubles, and stole thirty-one bases over sixty games.

[35] In 1932 Charleston became player-manager of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, whose roster included future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and Judy Johnson, in addition to teammates Ted Page, Jud Wilson, Jimmie Crutchfield, and Double Duty Radcliffe.

The two teams competed for more than a dozen Negro League championships and had several future Hall of Famers on their rosters, including Charleston.

[41] In 1945 at the age of 49, Charleston briefly came out of retirement and made appearances in both games of a doubleheader while managing the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers as a pinch hitter and defensive replacement at first base.

In 1945 Branch Rickey hired Charleston as manager of the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers in the United States League, but the team was short-lived.

Its main purpose was to scout talented black players for the first integrated Major League Baseball teams.

The Clowns captured the Negro American League pennant in 1954 before Charleston returned to Philadelphia, shortly before his death that fall.

[48] A renowned player of his era, Charleston was recognized for his athletic skills as a powerful, hard-hitting slugger, his speed and aggressiveness as a base runner, and as a top outfielder.

[49][50] Charleston ranks among Negro league baseball's top five players in home runs and batting average, and its leader in stolen bases.

[51] While The Sporting News list of the 100 greatest baseball players, published in 1998, ranked Charleston only sixty-seventh, only four other black ballplayers who played all or most of their careers in pre-1947 Negro leagues placed higher on the list: Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard, and Cool Papa Bell.

[55][56] In addition, Charleston's teammates and competitors such as Juanelo Mirabal, Buck O'Neil, and Turkey Stearnes, extol his greatness.

[50][19][57] “Oscar Charleston was Willie Mays before there was a Willie Mays,” said “Double Duty” Radcliffe shortly before his death in 2005, “except that he was a better base runner, a better center fielder and a better hitter.”[56] Hall of Fame manager John McGraw, whose career spanned forty years, once said, “If Oscar Charleston isn’t the greatest baseball player in the world, then I’m no judge of baseball talent.”[56] Renowned sportswriter Grantland Rice wrote a column on Charleston titled “No Greater Ball Player” in which he proclaimed: “It’s impossible for anybody to be a better ballplayer than Oscar Charleston.”[56]