Ostsiedlung

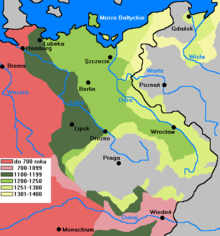

Larger treks of settlers, which included scholars, monks, missionaries, craftsmen and artisans, often invited, in numbers unverifiable, first moved eastwards during the mid-12th century.

The military territorial conquests and punitive expeditions of the Ottonian and Salian emperors during the 11th and 12th centuries do not form part of the Ostsiedlung, as these actions didn't result in any noteworthy settlement establishment east of the Elbe and Saale rivers.

The legal, cultural, linguistic, religious and economic changes caused by the movement had a profound influence on the history of Eastern Central Europe between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathians until the 20th century.

[19] The tribes that populated these marches were generally unreliable allies of the Empire, and successor kings led numerous, yet not always successful, military campaigns to maintain their authority.

In 843, the Carolingian Empire was partitioned into three independent kingdoms as a result of dissent among Charlemagne's three grandsons over the continuation of the custom of partible inheritance or the introduction of primogeniture.

Under the rule of King Louis the German and Arnulf of Carinthia, the first groups of civilian Catholic settlers were led by Franks and Bavarii to the lands of Pannonia (present-day Burgenland, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia).

[23][24] In 983, the Polabian Slavs in the Billung and Northern Marches, stretching from the Elbe river to the Baltic Sea succeeded in a rebellion against the political rule and Christian mission of the recently established Holy Roman Empire.

In spite of their new-won independence, the Obotrites, Rani, Liutizian and Hevelli tribes were soon faced with internal struggles and warfare as well as raids from the newly constituted and expanding Piast dynasty (the early Polish) state from the east, Denmark from the north and the Empire from the west, eager to reestablish her marches.

[30][31] Weakened by ongoing internal conflicts and constant warfare, the independent Wendish territories finally lost the capacity to provide effective military resistance.

According to Kantzow, in 1124 and 1128, Wartislaw I, Duke of Pomerania, at that time a vassal of Poland, invited bishop Otto of Bamberg to Christianize the Pomeranians and Liutizians of his duchy.

With the formation of the Hanseatic League, which allowed further German settlement in coastal towns due to it being the dominant trade republic in the Baltic and North seas.

[35] After the Wendish crusade, Albert the Bear was able to establish and expand the Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1157 on approximately the territory of the former Northern March, which since 983 had been controlled by the Hevelli and Lutici tribes.

After Henry the Lion lost his internal struggle with Emperor Frederick I, Mecklenburg and Pomerania became fiefs of the Holy Roman Empire in 1181,[37] although the latter briefly as it passed under Danish suzerainty in 1185, and then under Imperial again only in the 13th century.

German influence in Bohemia began when Duke Spytihněv I freed himself from Moravian vassalage and instead paid homage to the East Frankish King Arnulf of Carinthia at the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) in Regensburg in 895.

In 1080 Vratislav I, fighting under the banner of the Emperor, captured the golden lance of the papal counter-king, Rudolf of Swabia, at the battle of Flarchheim [citation needed].

The mountainous area settled first was the Eger Valley, partially due to its southern edges coming under the control of Diepold III who was an ally of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa.

Under the reign of Vladislaus II, various military orders, the most prominent of which, the Knights Hospitaller, were even allowed to bring German settlers into Bohemian land and settle them [citation needed].

A combination of the two construction methods was difficult because the horizontally stacked wood of the log room expands differently in height than the vertical posts of the framework.

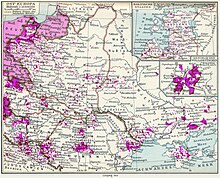

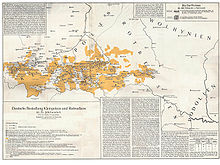

Settlement was the primary reason for the increase e.g. in the areas east of the Oder, the Duchy of Pomerania, western Greater Poland, Silesia, Austria, Moravia, Prussia and Transylvania, while in the larger part of Central and Eastern Europe indigenous populations were responsible for the growth.

Author Piskorski wrote that "insofar as it is possible to draw conclusions from the less than rich medieval source material, it appears that at least in some East Central European territories the population increased significantly.

Regardless of existing suburban settlements, locators were commissioned to establish completely new cities, as the goal was to attract as many people as possible in order to create new, flourishing population centers.

Settlers were invited by local secular rulers, such as dukes, counts, margraves, princes and (only in a few cases due to the weakening central power) the king.

Starting in the border marks, the princes invited people from the Empire by granting them land ownership and improved legal status, binding duties and the inheritance of the farm.

The agricultural, legal, administrative, and technical methods of the immigrants, as well as their successful Christianization of the native inhabitants, led to a gradual transformation of the settlement areas, as Slavic communities adopted German culture.

Wiprecht of Groitzsch, a prominent figure during the early German migration period only acquired local power through the marriage to a Slavic noblewoman and the support of the Bohemian king.

[citation needed] The former ethnic variety of German (Deutsch-) and Slavic (Wendisch-, Böhmisch-, Polnisch-) toponyms was discontinued by the Eastern European republics after World War II.

In Germany and some Slavic countries, most notably Poland, the Ostsiedlung was perceived in nationalist circles as a prelude to contemporary expansionism and Germanization efforts, the slogan used for this perception was Drang nach Osten (Drive or Push to the East).

[11][12][13] While further realization of this mega plan, aiming at a total reconstitution of Central and Eastern Europe as a German colony, was prevented by the war's turn, the beginning of the expulsion of 2 million Poles and settlement of Volksdeutsche in the annexed territories yet was implied by 1944.

[98][clarification needed] The Potsdam Conference – the meeting between the leaders of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union – sanctioned the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary.

The Soviet-established People's Republic of Poland annexed the majority of the lands, while the northern half of East Prussia was taken by the Soviets, becoming the Kaliningrad Oblast, an exclave of the Russian SFSR.