Ottoman music

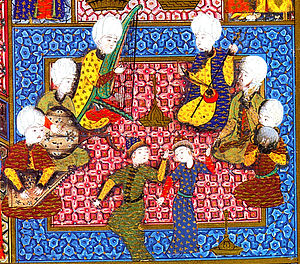

Developed in the palace, major Ottoman cities, and Sufi lodges, it traditionally features a solo singer with a small to medium-sized instrumental ensemble.

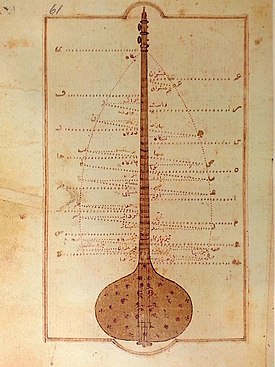

A wide variety of instruments has been used in Ottoman music, which include the turkish tanbur (lute), ney (end-blown reed flute), klasik kemençe (lyra), keman (violin), kanun (zither), and others.

This resulted in many classical musicians being forced to work in entertainment-related contexts, and gave rise to a much simpler style, named gazino.

"[6][7] Walter Zev Feldman, another researcher on Middle Eastern music, has therefore claimed that a uniquely Ottoman style emerged no earlier than the 1600s.

[6][10] While many peşrevs and semais, which were tightly integrated into Ottoman society, were widely enjoyed by the upper classes, these were often simplified, with a notable absence of long and complex rhythmic cycles.

"[6] Feldman further argues that this may have had two reasons: that the complicated forms of early Ottoman music made the older repertoire harder to consistently play without patronage of the court; or that the breakdown of transmission made it considerably more difficult for new performers to gain access to old works, creating a need for an older, more prestigious "great tradition" from which 17th century Ottoman music would emerge.

Cristaldi emphasizes that this era marked the beginning of contacts between Persian and Byzantine traditions, which would later fuse to form a recognizably Ottoman style.

[6][10] One of the most notable composers of "new synthesis" Ottoman classical music is Kasımpaşalı Osman Effendi, whose focus, along with his students, was on reviving the tradition of complex rhythmic cycles.

[10] Meanwhile, other students of Osman Effendi, such as Mustafa Itri, sought out the conventions of Byzantine music, incorporating the concepts of the Orthodox tradition into his works as well as his treatises.

This significantly bolstered the exchange between Byzantine and Ottoman music, and the resulting era featured a number of Greek composers, most notably Peter Peloponnesios, Hanende Zacharia and Tanburi Angeli.

A piece during this time might have been recorded as "Segâh makam, usûl muhammes, echos IV legetos", noting similarities and equivalences between the two systems.

The lack of a poetic style, as well as an empirical and practical focus, is said to set Cantemir's Edvar apart from earlier works, and would influence the treatises of later theorists.

"[5] While many in Sufi Muslim, Orthodox Christian and Jewish Maftirim traditions opposed this, and continued transferring the old style in their respective communities, official neglect made it very difficult for the system to function.

[21] The reforms on Turkish music strengthened from 1926 onward, when tekkes (Sufi lodges) were closed down, as a response to the ostensibly anti-Western, and thereby counter-revolutionary aspects of Sufism.

Further action was also taken to prevent Ottoman musicians from transmitting their knowledge to newer generations, as a "complete ban" was placed on Ottoman-style music education in 1927.

This was defended by poet and cultural figure Ercüment Behzat Lav, who argued that:[3] "What our millions require is neither mystical tekke music, nor wine, (...) nor wine-glass, nor beloved.

Tekelioğlu has argued that a major reason of this censorship is the republican elites' unwavering belief in absolute truths and a unified notion of "civilization", in which the technologically advanced West were superior in all of their traditions, including that of music, which in turn justified the policy "for the people's sake".

[12] Many Ottoman composers' names were Turkified to give the impression that they had converted and assimilated into Turko-Islamic culture, or otherwise demoted to a position of an outside influence helping the development of a Turkish music.

[2][22] While many were supportive of this new style, as it achieved widespread popularity, some musicians, including Erguner, have criticized it, arguing that the songs' lyrics lacked their traditional meaning and that its melodies were 'insipid'.

O'Connell argues that the name arabesk was a reiteration of an older orientalist dualism "to envisage a Turkish-Arab polarity", instead of an east–west one, and to define "aberrant [musical and cultural] practices with taxonomic efficiency".

[5] While older Ottoman-style musicians, such as Zeki Müren and Bülent Ersoy did deviate from republican gender norms, the ones exclusively associated with the more rural strand of arabesk, such as Kurdish vocalist İbrahim Tatlıses, presented a masculinity that, according to O'Connell, stressed both "swarthy machismo" and "profligate mannerisms", adopting the melismatic melodic contours of Ottoman singers, judged as effeminate and uncivilized by the earlier republican elite.

[24] Seyir is the concept of melodic progression in Ottoman music, disputed among theorists on its characteristics and classifications, and is still an often-researched topic.

[28] While there is a popular classification of seyirs, made by the Arel-Ezgi-Üzdilek system, which claims that makams can develop and resolve in ascending and descending fashions, this designation has faced criticism from Yöre among others, who has proposed a definition related to melodic contour.

Short usûls, generally dance oriented rhythmic cycles including sofyan and semaî, feature heavy correspondence with melodic lines and aruz meters.

He is rather a person experienced in the musical tradition, who – within certain rules – through the combination of basic elements of form, rhythm and melodic models, creates a new derivation.

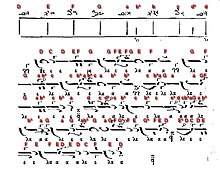

During the 17th century, Dimitrie Cantemir modified an old Islamic method called abjad serialization, where every pitch and note length were assigned Arabic letters and numerals respectively, to create his own influential system.

[34] A fasıl is led by a serhânende, who is responsible for indicating usûls, and the remaining musicians are called sazende (instrumentalist) or hânende (vocalist).

This tradition began with Dimitrie Cantemir, his Nağme-i Külliyat-ı Makamat (Ottoman Turkish for 'The song of the collection of makams'), features 36 modal modulations in total.

[11] Peşrevs, in addition to serving as preludes for long-form performances, also have a very comprehensive history in their usage as military marches, and therefore, has had a considerable influence on Western classical music.

Şarkı is a general name for urban songs which have been included in classical repertoire, principally after the 19th century, when the gazino style was created to counter the decline of Ottoman music.