Out-of-body experience

The term out-of-body experience was introduced in 1943 by G. N. M. Tyrrell in his book Apparitions,[1] and was adopted by researchers such as Celia Green,[2] and Robert Monroe,[3] as an alternative to belief-centric labels such as "astral projection" or "spirit walking".

[1] Some of the earliest researchers to write on the subject were Ernesto Bozzano, Hereward Carrington, Sylvan J. Muldoon, Arthur E. Powell and Francis Prevost.

A large percentage of these cases refer to situations where the sleep was not particularly deep (due to illness, noises in other rooms, emotional stress, exhaustion from overworking, frequent re-awakening, etc.).

Near-death experiences may include subjective impressions of being outside the physical body, sometimes visions of deceased relatives and religious figures, and transcendence of ego and spatiotemporal boundaries.

[44][45] James H. Hyslop (1912) wrote that OBEs occur when the activity of the subconscious mind dramatizes certain images to give the impression the subject is in a different physical location.

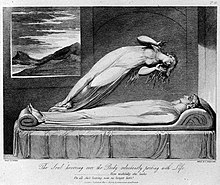

[53][54] According to (Irin and Watt, 2007) Jan Ehrenwald had described the out-of-body experience (OBE) "as an imaginal confirmation of the quest for immortality, a delusory attempt to assure ourselves that we possess a soul that exists independently of the physical body".

[55] The psychologists Donald Hebb (1960) and Cyril Burt (1968) wrote on the psychological interpretation of the OBE involving body image and visual imagery.

His theory involved a cognitive personality construct known as psychological absorption and gave instances of the classification of an OBE as examples of autoscopy, depersonalization and mental dissociation.

[70] In a case study involving 167 participants the findings revealed that those who claimed to have experienced the OBE were "more fantasy prone, higher in their belief in the paranormal and displayed greater somatoform dissociation.

"[73] In a study review of neurological and neurocognitive data (Bünning and Blanke, 2005) wrote that OBEs are due to "functional disintegration of lower-level multisensory processing and abnormal higher-level self-processing at the temporoparietal junction.

[75][76] Richard Wiseman (2011) has noted that OBE research has focused on finding a psychological explanation and "out-of-body experiences are not paranormal and do not provide evidence for the soul.

"[77] A study conducted by Jason Braithwaite and colleagues (2011) linked the OBE to "neural instabilities in the brain's temporal lobes and to errors in the body's sense of itself".

"[80] A study led by Josef Parvizi found that direct electrical stimulation of the anterior portion of the precuneus can induce an out-of-body experience.

[81] An early study that described alleged cases of OBE was the two-volume Phantasms of the Living, published in 1886 by the psychical researchers Edmund Gurney, Myers, and Frank Podmore.

Maria later told her social worker Kimberly Clark that during the OBE she had observed a tennis shoe on the third floor window ledge to the north side of the building.

They also discovered that the tennis shoe was easy to observe from outside the building and suggested that Maria may have overheard a comment about it during her three days in the hospital and then incorporated it into her OBE.

Her purpose was to provide a taxonomy of the different types of OBE, viewed simply as an anomalous perceptual experience or hallucination, while leaving open the question of whether some of the cases might incorporate information derived by extrasensory perception.

In 1999, at the 1st International Forum of Consciousness Research in Barcelona, research-practitioners Wagner Alegretti and Nanci Trivellato presented preliminary findings of an online survey on the out-of-body experience answered by internet users interested in the subject; therefore, not a sample representative of the general population.

The sleep paralysis and OBE correlation was later corroborated by the Out-of-Body Experience and Arousal study published in Neurology by Kevin Nelson and his colleagues from the University of Kentucky in 2007.

[106] Martin Gardner has written the experiment was not evidence for an OBE and suggested that whilst Tart was "snoring behind the window, Miss Z simply stood up in bed, without detaching the electrodes, and peeked.

British psychologist Susan Blackmore and others suggest that an OBE begins when a person loses contact with sensory input from the body while remaining conscious.

For example, Green[2] found that three quarters of a group of 176 subjects reporting a single OBE were lying down at the time of the experience, and of these 12% considered they had been asleep when it started.

[116][117] In neurologically normal subjects, Blanke and colleagues then showed that the conscious experience of the self and body being in the same location depends on multisensory integration in the TPJ.

Using event-related potentials, Blanke and colleagues showed the selective activation of the TPJ 330–400 ms after stimulus onset when healthy volunteers imagined themselves in the position and visual perspective that generally are reported by people experiencing spontaneous OBEs.

No such effects were found with stimulation of another site or for imagined spatial transformations of external objects, suggesting the selective implication of the TPJ in mental imagery of one's own body.

This leads Arzy et al. to argue that "these data show that distributed brain activity at the EBA and TPJ as well as their timing are crucial for the coding of the self as embodied and as spatially situated within the human body.

[120] In August 2007 Blanke's lab published research in Science demonstrating that conflicting visual-somatosensory input in virtual reality could disrupt the spatial unity between the self and the body.

"[124] In 2001, Sam Parnia and colleagues investigated out of body claims by placing figures on suspended boards facing the ceiling, not visible from the floor.

Among those who reported a perception of awareness and completed further interviews, 46% experienced a broad range of mental recollections in relation to death that were not compatible with the commonly used term of NDEs.

As of May 2016, a posting at the UK Clinical Trials Gateway website describes plans for AWARE II, a two-year multicenter observational study of 900–1,500 patients experiencing cardiac arrest, with subjects being recruited starting on 1 August 2014 and that the scheduled end date was 31 May 2017.