Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship

[8][9] Scholarly literary specialists consider the Oxfordian method of interpreting the plays and poems as grounded in an autobiographical fallacy, and argue that using his works to infer and construct a hypothetical author's biography is both unreliable and logically unsound.

[10][11][12][13][14] Oxfordian arguments rely heavily on biographical allusions; adherents find correspondences between incidents and circumstances in Oxford's life and events in Shakespeare's plays, sonnets, and longer poems.

Like other anti-Stratfordians before him, Looney referred to the absence of records concerning Shakespeare's education, his limited experience of the world, his allegedly poor handwriting skills (evidenced in his signatures), and the "dirt and ignorance" of Stratford at the time.

Looney referred to scholars who found in the plays evidence that their author was an expert in law, widely read in ancient Latin literature, and could speak French and Italian.

[24] Sigmund Freud, the novelist Marjorie Bowen, and several 20th-century celebrities found the thesis persuasive,[25][better source needed] and Oxford soon overtook Bacon as the favoured alternative candidate to Shakespeare, though academic Shakespearians mostly ignored the subject.

Looney's theory attracted a number of activist followers who published books supplementing his own and added new arguments, most notably Percy Allen, Bernard M. Ward, Louis P. Bénézet and Charles Wisner Barrell.

Mainstream scholar Steven W. May has noted that Oxfordians of this period made genuine contributions to knowledge of Elizabethan history, citing "Ward's quite competent biography of the Earl" and "Charles Wisner Barrell's identification of Edward Vere, Oxford's illegitimate son by Anne Vavasour" as examples.

After a period of decline of the Oxfordian theory beginning with World War II, in 1952 Dorothy and Charlton Greenwood Ogburn published the 1,300-page This Star of England, which briefly revived Oxfordism.

Though Crinkley rejected Ogburn's thesis, calling it "less satisfactory than the unsatisfactory orthodoxy it challenges", he believed that one merit of the book lay in how it forces orthodox scholars to reexamine their concept of Shakespeare as author.

[34] Spurred by Ogburn's book, "[i]n the last decade of the twentieth century members of the Oxfordian camp gathered strength and made a fresh assault on the Shakespearean citadel, hoping finally to unseat the man from Stratford and install de Vere in his place.

Its distributor, Sony Pictures, advertised that the film "presents a compelling portrait of Edward de Vere as the true author of Shakespeare's plays", and commissioned high school and college-level lesson plans to promote the authorship question to history and literature teachers across the United States.

[36] According to Sony Pictures, "the objective for our Anonymous program, as stated in the classroom literature, is 'to encourage critical thinking by challenging students to examine the theories about the authorship of Shakespeare's works and to formulate their own opinions.'

[49] Mainstream academics have often argued that the Oxford theory is based on snobbery: that anti-Stratfordians reject the idea that the son of a mere tradesman could write the plays and poems of Shakespeare.

[50][page needed] The Shakespeare Oxford Society has responded that this claim is "a substitute for reasoned responses to Oxfordian evidence and logic" and is merely an ad hominem attack.

[67][68] This view was first expressed by Charles Wisner Barrell, who argued that De Vere "kept the place as a literary hideaway where he could carry on his creative work without the interference of his father-in-law, Burghley, and other distractions of Court and city life.

Oxfordian William Farina refers to Shakespeare's apparent knowledge of the Jewish ghetto, Venetian architecture and laws in The Merchant of Venice, especially the city's "notorious Alien Statute".

According to Anderson, Oxford definitely visited Venice, Padua, Milan, Genoa, Palermo, Florence, Siena and Naples, and probably passed through Messina, Mantua and Verona, all cities used as settings by Shakespeare.

[95] In 2004, May wrote that Oxford's poetry was "one man's contribution to the rhetorical mainstream of an evolving Elizabethan poetic" and challenged readers to distinguish any of it from "the output of his mediocre mid-century contemporaries".

[108] Alan Nelson, de Vere's documentary biographer, writes that "[c]ontemporary observers such as Harvey, Webbe, Puttenham and Meres clearly exaggerated Oxford's talent in deference to his rank.

[18] Professor Jonathan Bate writes that Oxfordians cannot "provide any explanation for ... technical changes attendant on the King's Men's move to the Blackfriars theatre four years after their candidate's death ....

[139] Tom Veal has noted that the early play The Two Gentlemen of Verona reveals no familiarity on the playwright's part with Italy other than "a few place names and the scarcely recondite fact that the inhabitants were Roman Catholics.

[citation needed] Scholars contend that the composition date of Macbeth is one of the most overwhelming pieces of evidence against the Oxfordian position; the vast majority of critics believe the play was written in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot.

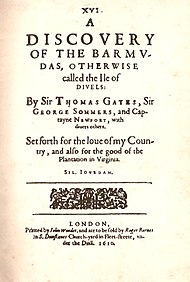

Jamestown, then little more than a rudimentary fort, was found in such a poor condition, with the majority of the previous settlers dead or dying, that Gates and Somers decided to abandon the settlement and the continent, returning everyone to England.

However, with the company believing all aboard the Sea Venture dead, a new governor, Baron De La Warr, had been sent with the Fourth Supply fleet, which arrived on 10 June 1610 as Jamestown was being abandoned.

Oxfordians have even claimed that the writers of the first-hand accounts of the real wreck based them on The Tempest, or, at least, the same antiquated sources that Shakespeare, or rather Oxford, is imagined to have used exclusively,[156] including Richard Eden's The Decades of the New Worlde Or West India (1555) and Desiderius Erasmus's Naufragium/The Shipwreck (1523).

He also writes that the alleged encryptions settle the question of the identity of "the Fair Youth" as Henry Wriothesley and contain striking references to the sonnets themselves and de Vere's relationship to Sir Philip Sidney and Ben Jonson.

[162] Literary scholars say that the idea that an author's work must reflect his or her life is a Modernist assumption not held by Elizabethan writers,[163] and that biographical interpretations of literature are unreliable in attributing authorship.

On Oxford's return from Europe in 1576, he encountered a cavalry division outside of Paris that was being led by a German duke,[citation needed] and his ship was hijacked by pirates who robbed him and left him stripped to his shirt, and who might have murdered him had not one of them recognised him.

In Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1, Falstaff and three roguish friends of Prince Hal also waylay unwary travellers at Gad's Hill, which is on the highway from Gravesend to Rochester.

As early as 1576, Edward de Vere was writing about this subject in his poem Loss of Good Name, which Steven W. May described as "a defiant lyric without precedent in English Renaissance verse.