Pali

[7][6]: 1 As such, the name of the language has caused some debate among scholars of all ages; the spelling of the name also varies, being found with both long "ā" [ɑː] and short "a" [a], and also with either a voiced retroflex lateral approximant [ɭ] or non-retroflex [l] "l" sound.

[9] However, modern scholarship has regarded Pali as a mix of several Prakrit languages from around the 3rd century BCE, combined and partially Sanskritized.

[12] Pali has some commonalities with both the western Ashokan Edicts at Girnar in Saurashtra, and the Central-Western Prakrit found in the eastern Hathigumpha inscription.

[6] Scholars consider it likely that he taught in several closely related dialects of Middle Indo-Aryan, which had a high degree of mutual intelligibility.

[6]: 6 In Sri Lanka, Pali is thought to have entered into a period of decline ending around the 4th or 5th century (as Sanskrit rose in prominence, and simultaneously, as Buddhism's adherents became a smaller portion of the subcontinent), but ultimately survived.

[citation needed] With only a few possible exceptions, the entire corpus of Pali texts known today is believed to derive from the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya in Sri Lanka.

[12] While literary evidence exists of Theravadins in mainland India surviving into the 13th century, no Pali texts specifically attributable to this tradition have been recovered.

[12] The earliest inscriptions in Pali found in mainland Southeast Asia are from the first millennium CE, some possibly dating to as early as the 4th century.

[12] By the 11th century, a so-called "Pali renaissance" began in the vicinity of Pagan, gradually spreading to the rest of mainland Southeast Asia as royal dynasties sponsored monastic lineages derived from the Mahavihara of Anuradhapura.

[16] One milestone of this period was the publication of the Subodhalankara during the 14th century, a work attributed to Sangharakkhita Mahāsāmi and modeled on the Sanskrit Kavyadarsa.

[12] During this era, correspondences between royal courts in Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia were conducted in Pali, and grammars aimed at speakers of Sinhala, Burmese, and other languages were produced.

[18][19] The earliest samples of Pali discovered are inscriptions believed to date from 5th to 8th century located in mainland Southeast Asia, specifically central Siam and lower Burma.

[19] These inscriptions typically consist of short excerpts from the Pali Canon and non-canonical texts, and include several examples of the Ye dhamma hetu verse.

[26] R. C. Childers, who held to the theory that Pali was Old Magadhi, wrote: "Had Gautama never preached, it is unlikely that Magadhese would have been distinguished from the many other vernaculars of Hindustan, except perhaps by an inherent grace and strength which make it a sort of Tuscan among the Prakrits.

[6]: 5 Following this period, the language underwent a small degree of Sanskritisation (i.e., MIA bamhana > brahmana, tta > tva in some cases).

He goes on to write: Scholars regard this language as a hybrid showing features of several Prakrit dialects used around the third century BCE, subjected to a partial process of Sanskritization.

[30] This view of language naturally extended to Pali and may have contributed to its usage (as an approximation or standardization of local Middle Indic dialects) in place of Sanskrit.

[31][6]: 2 Comparable to Ancient Egyptian, Latin or Hebrew in the mystic traditions of the West, Pali recitations were often thought to have a supernatural power (which could be attributed to their meaning, the character of the reciter, or the qualities of the language itself), and in the early strata of Buddhist literature we can already see Pali dhāraṇīs used as charms, as, for example, against the bite of snakes.

In Thailand, the chanting of a portion of the Abhidhammapiṭaka is believed to be beneficial to the recently departed, and this ceremony routinely occupies as much as seven working days.

The great centres of Pali learning remain in Sri Lanka and other Theravada nations of Southeast Asia: Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia.

The 13th-century Tibetan historian Buton Rinchen Drub wrote that the early Buddhist schools were separated by choice of sacred language: the Mahāsāṃghikas used Prakrit, the Sarvāstivādins used Sanskrit, the Sthaviravādins used Paiśācī, and the Saṃmitīya used Apabhraṃśa.

Its use later expanded southeast to include some regions of modern-day Bengal, Odisha, and Assam, and it was used in some Prakrit dramas to represent vernacular dialogue.

Preserved examples of Magadhi Prakrit are from several centuries after the theorized lifetime of the Buddha, and include inscriptions attributed to Asoka Maurya.

However, scholarly interest in the language has been focused upon religious and philosophical literature, because of the unique window it opens on one phase in the development of Buddhism.

; Pali: niggahīta), represented by the letter ṁ (ISO 15919) or ṃ (ALA-LC) in romanization, and by a raised dot in most traditional alphabets, originally marked the fact that the preceding vowel was nasalized.

Emperor Ashoka erected a number of pillars with his edicts in at least three regional Prakrit languages in Brahmi script,[45] all of which are quite similar to Pali.

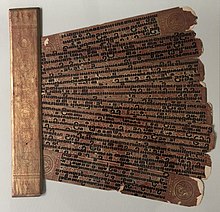

Historically, the first written record of the Pali canon is believed to have been composed in Sri Lanka, based on a prior oral tradition.

According to the Mahavamsa (the chronicle of Sri Lanka), due to a major famine in the country Buddhist monks wrote down the Pali canon during the time of King Vattagamini in 100 BCE.

However, older ASCII fonts such as Leedsbit PaliTranslit, Times_Norman, Times_CSX+, Skt Times, Vri RomanPali CN/CB etc., are not recommendable, they are deprecated, since they are not compatible with one another, and are technically out of date.

'[50] Similarly, in 20th century Thailand and Laos, local scholars, including Jit Bhumisak and Vajiravudh coined new words using Pali roots to describe foreign concepts and technological innovations.