PLATO (computer system)

By the late 1970s, it supported several thousand graphics terminals distributed worldwide, running on nearly a dozen different networked mainframe computers.

CDC President William Norris planned to make PLATO a force in the computer world, but found that marketing the system was not as easy as hoped.

The USSR's 1957 launching of the Sputnik I artificial satellite energized the United States' government into spending more on science and engineering education.

In 1958, the U.S. Air Force's Office of Scientific Research had a conference about the topic of computer instruction at the University of Pennsylvania; interested parties, notably IBM, presented studies.

Before conceding failure, Alpert mentioned the matter to laboratory assistant Donald Bitzer, who had been thinking about the problem, suggesting he could build a demonstration system.

It included a television set for display and a special keyboard for navigating the system's function menus;[5] PLATO II, in 1961, featured two users at once, one of the first implementations of multi-user time-sharing.

Accordingly, in 1967, the National Science Foundation granted the team steady funding, allowing Alpert to set up the Computer-based Education Research Laboratory (CERL) at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign campus.

From a strict business perspective, he was evolving Control Data into a service-based company instead of a hardware one, and was increasingly convinced that computer-based education would become a major market in the future.

In the early 1980s, CDC started heavily advertising the service, apparently due to increasing internal dissent over the now $600 million project, taking out print and even radio ads promoting it as a general tool.

An official evaluation by an external testing agency ended with roughly the same conclusions, suggesting that everyone enjoyed using it, but it was essentially equal to an average human teacher in terms of student advancement.

However, CDC charged $50 an hour for access to their data center, in order to recoup some of their development costs, making it considerably more expensive than a human on a per-student basis.

This was made possible by PLATO's groundbreaking communication and interface capabilities, features whose significance is only lately being recognized by computer historians.

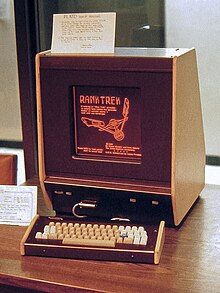

[citation needed] PLATO's plasma panels were well suited to games, although its I/O bandwidth (180 characters per second or 60 graphic lines per second) was relatively slow.

[citation needed] PLATO courseware covers a full range of high-school and college courses, as well as topics such as reading skills, family planning, Lamaze training and home budgeting.

The PLATO hardware and software supported the design and use of one's own 8-by-16 characters, so most languages could be displayed on the graphics screen (including those written right-to-left).

In 1969, G. David Peters began researching the feasibility of using PLATO to teach trumpet students to play with increased pitch and rhythmic precision.

[23] Placek used the random access audio device attached to a PLATO III terminal for which he developed music notation fonts and graphics.

In timed class exercises, trainees briefly viewed slides and recorded their diagnoses on the checklists which were reviewed and evaluated later in the training session.

[26] In 1967, Allvin and Kuhn used a four-channel tape recorder interfaced to a computer to present pre-recorded models to judge sight-singing performances.

[27] In 1969, Ned C. Deihl and Rudolph E. Radocy conducted a computer-assisted instruction study in music that included discriminating aural concepts related to phrasing, articulation, and rhythm on the clarinet.

Many alumni of the University of Illinois School of Music PLATO Project gained early hands-on experience in computing and media technologies and moved into influential positions in both education and the private sector.

During the 1970s Michael Stein, E. Clarke Porter and PLATO veteran Jim Ghesquiere, in cooperation with NASD executive Frank McAuliffe, developed the first "on-demand" proctored commercial testing service.

Applying many of the PLATO concepts used in the late 1970s, E. Clarke Porter led the Drake Training and Technologies testing business (today Thomson Prometric) in partnership with Novell, Inc. away from the mainframe model to a LAN-based client server architecture and changed the business model to deploy proctored testing at thousands of independent training organizations on a global scale.

Pearson VUE was founded by PLATO/Prometric veterans E. Clarke Porter, Steve Nordberg and Kirk Lundeen in 1994 to further expand the global testing infrastructure.

Dr. Stanley Trollip (formerly of the University of Illinois Aviation Research Lab) and Gary Brown (formerly of Control Data) developed the prototype of The Examiner System in 1984.

CDC eventually sold the "PLATO" trademark and some courseware marketing segment rights to the newly formed The Roach Organization (TRO) in 1989.

The Evergreen State College received several grants from CDC to implement computer language interpreters and associated programming instruction.

[36] Royalties received from the PLATO computer-aided instruction materials developed at Evergreen support technology grants and an annual lecture series on computer-related topics.

Eskom, the South African electrical power company, had a large CDC mainframe at Megawatt Park in the northwest suburbs of Johannesburg.

This version of PLATO runs on a free and open-source software emulation of the original CDC hardware called Desktop Cyber.