Palaeolama

[2] Analyses of their limb elements reveal that they had shorter, stockier metapodials, and longer epipodials, giving them a short, stocky appearance.

[8][4] Various dietary analyses have concluded that Palaeolama was a specialized forest browser that relied almost exclusively on plants high in C3 for subsistence.

[9][4][11] Additionally, its shallow jaw and brachydont "cheek teeth" are highly suggestive of a mixed or intermediate seasonal diet consisting of primarily leaves and fruits, with some grass.

[4] Analysis of δ13C values from P. major remains in northeastern Brazil confirm it was primarily a consumer of C3 plant matter.

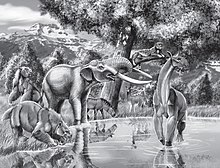

[4] Fossil evidence suggests Palaeolama was primarily adapted to low-temperate, arid climates and preferred open, forested, and high-altitude mountainous regions.

[8][10][4] The distribution of fossil evidence suggests that they had an altitudinal range limited exclusively by their dietary (vegetation) requirements.

[7][8][10] Palaeolama mirifica, the "stout-legged llama", is known from southern California and the Southeastern U.S., with the highest concentration of fossil specimens found in Florida (specifically the counties of Alachua, Citrus, Hillsborough, Manatee, Polk, Brevard, Orange, Sumter, and Levy).

[8] Palaeolama wedelli, identified by Gervais in 1855, lived during the Mid- to Late Pleistocene, with fossil specimens found in southern Bolivia and the Andean region of Ecuador.

[4][2] Evidence from both the paleoecological and fossil records suggest that Palaeolama, among other extinct camelids, weathered a number of glacial and interglacial episodes throughout their existence in North and South America.

Their disappearance in some regions has been shown to coincide with a change in climate (to warmer, humid conditions) occurring at the end of the Pleistocene (also known as the Late Quaternary warming) suggesting an inability to persevere.