Paleontology in Wyoming

"[2] Murray has also written that nearly every major vertebrate paleontologist in United States history has collected fossils in Wyoming.

This sea remained in place during the early Paleozoic era and would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, ostracoderms, and trilobites.

During the early part of the Cenozoic, Wyoming was home to massive lakes inhabited by Knightia fish and dense forests.

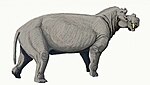

On land the state would come to be inhabited by camelids, carnivorans, creodonts, the seven foot tall flightless bird Gastornis, proboscideans, equids, primates, rodents, and Uintatherium.

Local Native Americans have known about fossils for thousands of years and have both applied them to practical purposes and devised myths to explain them.

[6] Some Triassic red beds in Wyoming preserve unusual "scrape mark" trace fossils that were likely left by a swimming animal.

[3] During the Jurassic, the area of Wyoming now called Dinosaur Canyon was home to primitive relatives of modern crocodilians and mammals.

Enchodus was a relative of modern salmon and its long fangs earned it the misleading nickname "the sabre-toothed herring".

Enchodus was so abundant that roughly one quarter of the fossils left in the state's Pierre Shale deposits are attributable to the genus.

One Cimolichthys suffocated when its would-be prey, a sizable squid called Tusoteuthis longa, was too large to swallow completely and blocked the fish's gills.

Western Interior Seaway researcher Michael J. Everhart has called the specimen "[o]ne of the strangest 'death by gluttony' occurrences in the fossil record".

[4]Late Cretaceous fossil dinosaur footprints are surprisingly rare in Wyoming compared to other western states with contemporary deposits.

Other land life of Eocene Wyoming include creodonts and a wide variety of insects that left their remains near Henry's Fork, not far from the boundary with neighboring Utah.

The Bridger Basin was home to creatures like relatives of camels, carnivorans, elephants, horses, primates, rodents, Uintatherium, and whales.

[3] Evidence for knowledge about fossils among the indigenous peoples of Wyoming stretches at least 11,000 years into the past, as a mammoth kill site of that age located in the Big Horn Basin that contains dinosaur stomach stones.

The Clovis people who collected the gastroliths from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation probably intended to use them as hammer stones.

[19] Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus fossils in the Late Cretaceous Lance Creek Formation of Wyoming may have shared responsibility for inspiring Cheyenne myths about a kind of monster called an ahke.

[21] The Hi stowunini hotua, or double-toothed bull is another creature from local Cheyenne mythology that may have been inspired by fossils remains or cultural memories of actual ancient life.

Remains of this interval from the eastern part of the state as well as western Nebraska and South Dakota would have been familiar to the Cheyenne.

Relevant fossil wildlife that may have contributed to the double-toothed bull myth include animals large canids, saber-toothed cats, creodonts, oreodonts, or rhinoceroses.

[22] One of the earliest fossil hunting excursions into Wyoming happened in 1870, when O. C. Marsh led an expedition into the state on behalf of Yale.

These were Colorado School of Mines professor Arthur Lakes, teacher O. Lucas, and Union Pacific Railroad foreman William H. Reed.

[2] In March 1877, Reed noticed fossil limbs and vertebrae at Como Bluff while returning to the railroad station after hunting.

There they found the first Jurassic pterosaur known from North America, and a new genus and species of herbivorous dinosaur; Dryosaurus altus.

[2] Late in 1877, Marsh's scientific rival Edward Drinker Cope heard that fossils had been discovered at Como Bluff.

Reed was essentially on his own by the spring of 1879, working hectically at excavating several quarries at once to recover the fossils before Cope's men.

[26] In the middle of May that same year Marsh directed Arthur Lakes to leave the Morrison, Colorado area and assist Reed at Como Bluff.

Fossils of Unitatherium are relatively common, but the specimen uncovered by Gazin's expedition was exceptionally complete and in high quality preservation.

The crew's excavations in the Bison Basin uncovered the jaws and teeth of at least four species in two genera of plesiadapids, primitive primates related to modern lemurs.

They also found herbivorous condylarth fossils one of these, Phenacodus, was more than four feet long, which makes it unusually large for the group.