Mandate for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was passed on 29 November 1947; this envisaged the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states operating under economic union, and with Jerusalem transferred to UN trusteeship.

The release of the Balfour Declaration was authorised by 31 October; the preceding Cabinet discussion had mentioned perceived propaganda benefits amongst the worldwide Jewish community for the Allied war effort.

[10][11][12] The second half of the declaration was added to satisfy opponents of the policy, who said that it would otherwise prejudice the position of the local population of Palestine and encourage antisemitism worldwide by (according to the presidents of the Conjoint Committee, David L. Alexander and Claude Montefiore in a letter to the Times) "stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands".

[15] Between July 1915 and March 1916, a series of ten letters were exchanged between Sharif Hussein bin Ali, the head of the Hashemite family that had ruled the Hejaz as vassals for almost a millennium, and Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner to Egypt.

[25] The mandate system was created in the wake of World War I as a compromise between Woodrow Wilson's ideal of self-determination, set out in his Fourteen Points speech of January 1918, and the European powers' desire for gains for their empires.

The 29 January memorandum[36] stipulated that "from the line Alexandretta – Diarbekr southward to the Indian Ocean" (with the boundaries of any new states) were "matters for arrangement between us, after the wishes of their respective inhabitants have been ascertained", in a reference to Woodrow Wilson's policy of self-determination.

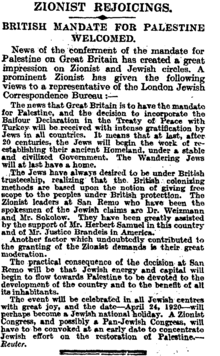

"[39][40] The World Zionist Organization delegation to the Peace Conference – led by Chaim Weizmann, who had been the driving force behind the Balfour Declaration – also asked for a British mandate, asserting the "historic title of the Jewish people to Palestine".

British forces retreated in spring 1918 from Transjordan after their first and second attacks on the territory,[50] indicating their political ideas about its future; they had intended the area to become part of an Arab Syrian state.

The French formed a new Damascus state after the battle, and refrained from extending their rule into the southern part of Faisal's domain; Transjordan became for a time a no-man's land[d] or, as Samuel put it, "politically derelict".

"[67][68] Samuel replied to Curzon, "After the fall of Damascus a fortnight ago ... Sheiks and tribes east of Jordan utterly dissatisfied with Shareefian Government most unlikely would accept revival",[69][70] and asked to put parts of Transjordan directly under his administrative control.

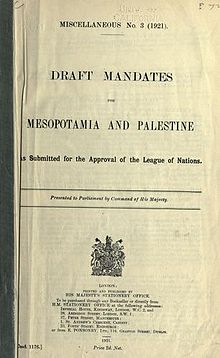

[h] The intended mandatory powers were required to submit written statements to the League of Nations during the Paris Peace Conference proposing the rules of administration in the mandated areas.

[xviii][90] In the spring of 1919 the experts of the British Delegation of the Peace Conference in Paris opened informal discussions with representatives of the Zionist Organisation on the draft of a Mandate for Palestine.

Towards the end of 1919 the British Delegation returned to London and as during the protracted negotiations Dr. Weizmann was often unavoidably absent in Palestine, and Mr. Sokolow in Paris, the work was carried on for some time by a temporary political committee, of which the Right Hon.

When Curzon received the draft of 15 March 1920, he was "far more critical"[98] and objected to "... formulations that would imply recognition of any legal rights ..." (for example, that the British government would be "responsible for placing Palestine under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of a Jewish national home and the development of a self-governing Commonwealth ...").

[103]The new article was intended to enable Britain "to set up an Arab administration and to withhold indefinitely the application of those clauses of the mandate which relate to the establishment of the National Home for the Jews", as explained in a Colonial Office letter three days later.

[106] Churchill said that Transjordan would not form part of the Jewish national home to be established west of the River Jordan:[107][108][xxi][xxii] Trans-Jordania would not be included in the present administrative system of Palestine, and therefore the Zionist clauses of the mandate would not apply.

[118][119][120] Musa al-Husayni led a 1922 delegation to Ankara and then to the Lausanne Conference, where (after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's victories against the Greek army in Turkey) the Treaty of Sèvres was about to be re-negotiated.

[121] Each of the principal Allied powers had a hand in drafting the proposed mandate, although some (including the United States) had not declared war on the Ottoman Empire and did not become members of the League of Nations.

[xxv] I do not attach undue importance to this movement, but it is increasingly difficult to meet the argument that it is unfair to ask the British taxpayer, already overwhelmed with taxation, to bear the cost of imposing on Palestine an unpopular policy.

[xxxi] On 16 September 1922, the League of Nations approved a British memorandum detailing its intended implementation of the clause excluding Transjordan from the articles related to Jewish settlement.

Lord Balfour suggested an alternative which was accepted and included in the preamble immediately after the paragraph quoted above: Whereas recognition has thereby [i.e. by the Treaty of Sèvres] been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine, and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country;[179]In the body of the document, the Zionist Organization was mentioned in Article 4; in the September 1920 draft, a qualification was added which required that "its organisation and constitution" must be "in the opinion of the Mandatory appropriate".

[i] This would, according to professor of modern Jewish history Bernard Wasserstein, result in "the myth of Palestine's 'first partition' [which became] part of the concept of 'Greater Israel' and of the ideology of Jabotinsky's Revisionist movement".

[ii][iii] Palestinian-American academic Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, then chair of the Northwestern University political science department, suggested that the "Jordan as a Palestinian State" references made by Israeli spokespeople may reflect "the same [mis]understanding".

On 25 April 1923, five months before the mandate came into force, the independent administration was recognised in a statement made in Amman: Subject to the approval of the League of Nations, His Britannic Majesty will recognise the existence of an independent Government in Trans-jordan under the rule of His Highness the Amir Abdullah, provided that such Government is constitutional and places His Britannic Majesty in a position to fulfil his international obligations in respect of the territory by means of an Agreement to be concluded with His Highness.

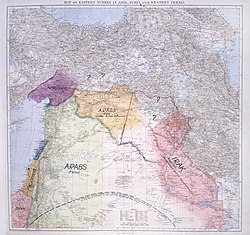

[206][better source needed] These borders included present day Israel and the Israeli-occupied territories, western Jordan, southwestern Syria and southern Lebanon "in the vicinity south of Sidon".

The commission submitted its final report on 3 February 1922; it was approved with some caveats by the British and French governments on 7 March 1923, several months before Britain and France assumed their mandatory responsibilities on 29 September 1923.

[225] After the settlement of the northern-border issue, the British and French governments signed an agreement of good neighbourly relations between the mandated territories of Palestine, Syria and Lebanon on 2 February 1926.

[xxxvi] No agreement was reached in Paris; the topic was not discussed at the April 1920 San Remo conference, at which the boundaries of the "Palestine" and "Syria" mandates were left unspecified to "be determined by the Principal Allied Powers" at a later stage.

[240] This followed a proposal from T.E.Lawrence in January 1922 that Transjordan be extended to include Wadi Sirhan as far south as al-Jauf, in order to protect Britain's route to India and contain Ibn Saud.

[242] The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was passed on 29 November 1947; this envisaged the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states operating under economic union, and with Jerusalem transferred to UN trusteeship.