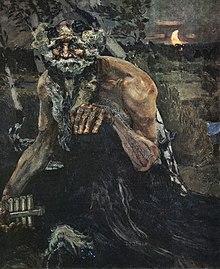

Pan (god)

With his homeland in rustic Arcadia, he is also recognized as the god of fields, groves, wooded glens, and often affiliated with sex; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the season of spring.

[10][11] The familiar form of the name Pan is contracted from earlier Πάων, derived from the root *peh₂- (guard, watch over).

[15] Being a rustic god, Pan was not worshipped in temples or other built edifices, but in natural settings, usually caves or grottoes such as the one on the north slope of the Acropolis of Athens.

[32] Other sources (Duris of Samos; the Vergilian commentator Servius) report that Penelope slept with all 108 suitors in Odysseus' absence, and gave birth to Pan as a result.

[35] Like other nature spirits, Pan appears to be older than the Olympians, if it is true that he gave Artemis her hunting dogs and taught the secret of prophecy to Apollo.

The constellation Capricornus is traditionally depicted as a sea-goat, a goat with a fish's tail (see "Goatlike" Aigaion called Briareos, one of the Hecatonchires).

Diogenes of Sinope, speaking in jest, related a myth of Pan learning masturbation from his father, Hermes, and teaching the habit to shepherds.

"[47] Disturbed in his secluded afternoon naps, Pan's angry shout inspired panic (panikon deima) in lonely places.

[50] In two late Roman sources, Hyginus[51] and Ovid,[52] Pan is substituted for the satyr Marsyas in the theme of a musical competition (agon), and the punishment by flaying is omitted.

Pan blew on his pipes and gave great satisfaction with his rustic melody to himself and to his faithful follower, Midas, who happened to be present.

Their names were Kelaineus, Argennon, Aigikoros, Eugeneios, Omester, Daphoenus, Phobos, Philamnos, Xanthos, Glaukos, Argos, and Phorbas.

[56] In Rabelais' Fourth Book of Pantagruel (sixteenth century), the Giant Pantagruel, after recollecting the tale as told by Plutarch, opines that the announcement was actually about the death of Jesus Christ, which did take place at about the same time (towards the end of Tiberius' reign), noting the aptness of the name: "for he may lawfully be said in the Greek tongue to be Pan, since he is our all.

[58] The nineteenth-century visionary Anne Catherine Emmerich, in a twist echoed nowhere else, claims that the phrase "the Great Pan" was actually a demonic epithet for Jesus Christ, and that "Thamus, or Tramus" was a watchman in the port of Nicaea, who, at the time of the other spectacular events surrounding Christ's death, was then commissioned to spread this message, which was later garbled "in repetition.

"[60][61][62] It was interpreted with concurrent meanings in all four modes of medieval exegesis: literally as historical fact, and allegorically as the death of the ancient order at the coming of the new.

Van Teslaar explains, "[i]n its true form the phrase would have probably carried no meaning to those on board who must have been unfamiliar with the worship of Tammuz which was a transplanted, and for those parts, therefore, an exotic custom.

The cry "The Great Pan is dead" has appealed to poets, such as John Milton, in his ecstatic celebration of Christian peace, On the Morning of Christ's Nativity line 89,[67] Elizabeth Barrett Browning,[68] and Louisa May Alcott.

Douglas Bush notes, "The goat-god, the tutelary divinity of shepherds, had long been allegorized on various levels, from Christ to 'Universall Nature' (Sandys); here he becomes the symbol of the romantic imagination, of supra-mortal knowledge.

Peter Pan's character is both charming and selfish - emphasizing our cultural confusion about whether human instincts are natural and good, or uncivilised and bad.

[76] In an article in Hellebore magazine, Melissa Edmundson argues that women writers from the nineteenth century used the figure of Pan "to reclaim agency in texts that explored female empowerment and sexual liberation".

In Eleanor Farjeon's poem "Pan-Worship", the speaker tries to summon Pan to life after feeling "a craving in me", wishing for a "spring-tide" that will replace the stagnant "autumn" of the soul.

A dark version of Pan's seductiveness appears in Margery Lawrence's Robin's Rath, both giving and taking life and vitality.

Grahame's Pan, unnamed but clearly recognisable, is a powerful but secretive nature-god, protector of animals, who casts a spell of forgetfulness on all those he helps.

The goat-footed god entices villagers to listen to his pipes as if in a trance in Lord Dunsany's novel The Blessing of Pan (1927).

Some of the detailed illustrated depictions of Pan included in the volume are by the artists Giorgio Ghisi, Sir James Thornhill, Bernard Picart, Agostino Veneziano, Vincenzo Cartari, and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

Syrinx, written as part of incidental music to the play Psyché by Gabriel Mourey, was originally called "Flûte de Pan".

Inspired by characters from Ovid's fifteen-volume work Metamorphoses, Britten titled the movement, "Pan: who played upon the reed pipe which was Syrinx, his beloved."

The British rock band Pink Floyd named its first album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn in reference to Pan as he appears in The Wind in the Willows.

[79] In the English town of Painswick in Gloucestershire, a group of eighteenth-century gentry, led by Benjamin Hyett, organised an annual procession dedicated to Pan, during which a statue of the deity was held aloft, and people shouted "Highgates!

[80] Occultists Aleister Crowley and Victor Neuburg built an altar to Pan on Da'leh Addin, a mountain in Algeria, where they performed a magic ceremony to summon the god.

In Wicca, the archetype of the Horned God is highly important, as represented by such deities as the Celtic Cernunnos, the Hindu Pashupati, and the Greek Pan.