Papadic Octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed "Octoechos"; Greek: ὁ Ὀκτώηχος, pronounced in Constantinopolitan: Ancient Greek pronunciation: [oxˈtóixos];[1] from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, Osmoglasie from о́смь "eight" and гласъ "voice, sound") is the name of the eight mode system used for the composition of religious chant in Byzantine, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, Latin and Slavic churches since the Middle Ages.

Until 1204 neither the Hagia Sophia nor any other cathedral of the Byzantine Empire did abandon its habits, and the Hagiopolitan eight mode system came into use not earlier than in the mixed rite of Constantinople, after the patriarchate and the court had returned from their exile in Nikaia in 1261.

Because the repertoire of signs was expanded under the influence of John Glykys' school, there was a scholarly discussion to make a distinction between Middle and Late Byzantine notation.

These models followed the octoechos and showed close resemblance to the melismatic compositions of the cathedral rite, at least in the transmission of psaltikon in Middle Byzantine notation, from which the expression of psaltic art had been taken.

Traditional (palaia) forms of elaboration were often named after their local secular tradition as Constantinopolitan (agiosophitikon, politikon), Thessalonican (thessalonikaion), or a monastic one like those from Athos (hagioreitikon), the more elaborated, kalophonic compositions were collected in separate parts of the akolouthiai, especially the poetic and musical compositions over the Polyeleos-Psalm developed as a new genre of psaltic art and the names of the protopsaltes or maistoroi were mentioned in these collections.

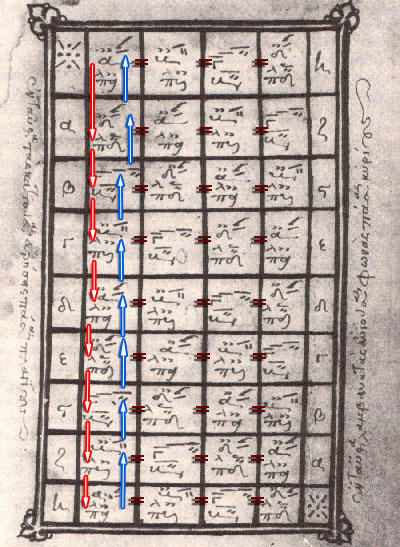

According to the Papadic "method of parallage (solfeggio)", the logic of one column did not to represent the pentachord between kyrios and plagios of the same octave species, but the connection between a change of direction as α'↔πλδ', β'↔πλα', γ'↔πλβ', and δ'↔υαρ.

on a:) α' πλδ' υαρ πλβ' πλα' β' γ' δ' α'But there is no demonstration of the descending parallage, neither within the tree nor by any additional example.

The simplest and presumably earliest form which is also the closest to Ancient Greek science treatises, is the representation of the different metabolai kata tonon (μεταβολαὶ κατὰ τόνον) by the kanōnion (also used in the translation by Boethius).

As example the Doxastarion oktaechon Θεαρχίῳ νεύματι, one of the stichera which passes through all the echoi of the octoechos, in the short realization of Petros Peleponnesios finds the echos tritos "on the wrong pitch".

The τροχὸς in the version of a late 18th-century manuscript of Papadike adds the aspect of the heptaphonic tone system to the peripheral wheels, dedicated to the diatonic kyrios and plagios of the four octaves.

This method follows exactly the Latin description of alia musica, whose author probably referred to the opinion of an experienced psaltes: For the full octave another tone might be added, which is called ἐμμελῆς: "according to the melos".

Instead the Papadike just contained systematic lists of signs and parallage diagrams, but it also offered useful exercises which aimed to teach different methods of how to create a melos during performance.

In the later treatises about psaltic art (15th century), which offer further explanations to the Papadike like those by Gabriel Hieromonachos, Manuel Chrysaphes, and by Ioannis Plousiadinos, there was obviously only a problem of ignorance, but not the Western one that the tetraphonic system excluded the heptaphonic and vice versa.

τοίνυν ψαλτικὴ ἐπιστήμη οὐ συνίσταται μόνον ἀπὸ παραλλαγῶν, ὡς τῶν νῦν τινες οἴονται, ἀλλὰ καὶ δι’ ἄλλων πολλῶν πρότων, οὕς αὐτίκα λέξω διὰ βραχέων.

[36] The "Occidental school" as Maria Alexandru liked to call it, went into the footsteps of Chrysanthos with their assumption that the systema teleion or heptaphonia was the only explanation and was adapted according to the Western perception of the modes as octave species.

The great wheel in the center rather represented all phthongoi as an element of a tone system, but by the solfeggio of parallage each phthongos was defined on the level of dynamis (δύναμις) as an own echos according to a certain enechema.

The four inner rings of the central wheel re-defined the dynamis of each phthongos constantly by the enechema of another echos, so each parallage defined the disposition of the intervals in another way, thus represented all possible transpositions as part of the outer nature.

[39] The psaltes skilled in the psaltic art usually opened his performance by an extended enechema which recapitulated the disposition of all the echoi which the kalophonic melos had to pass through.

[40] There is an alternative form of solfeggio which was called "the wisest or rather sophisticated parallage of Mr Ioannis Iereos Plousiadinos" (ἡ σοφωτάτη παραλλαγὴ κυρίου Ἰωάννου Ἰερέως τοῦ Πλουσιαδηνοῦ).

πλὴν ἡ κατάληξις ταύτης γίνεται πάντοτε εἰς τὸν πλάγιον δευτέρου, κἂν εἰς ὁποῖον ἦχον καὶ τεθῇ, καθὼς διδάσκει καὶ ποιεῖ τοῦτο ὁ ἀληθὴς εὐμουσώτατος διδάσκαλος μαΐστωρ Ἰωάννης εἰς τὸ "Μήποτε ὀργισθῆ κύριος" ἐν τῷ "Δουλεύσατε"· τετάρτου γὰρ ἤχου ὄντος ἐκεῖ ἀπὸ παραλλαγῶν, δεσμεῖ τοῦτον ἡ φθορὰ αὕτη καὶ ἀντὶ τοῦ κατελθεῖν πλάγιον πρώτου, κατέρχεταιεἰς τὸν πλάγιον δευτέρου.And this is the situation, but its melody [μέλος] does not always belong to the first mode for frequently, by binding the third mode also, it makes it nenano, likewise the fourth plagal mode.

In this respect Maria Alexandru's "approaches towards a critical edition" are quite helpful, because a comparison assumes that the didactic chant Mega Ison had been originally untransposed, while there are enough later versions which need several transpositions (μεταβολαὶ κατὰ τόνον).

The section of echos plagios tou devterou (ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ δευτέρου) is the longest and most complex one and it has some medial signatures for the phthora nenano which is resolved frequently, especially when it is used before the great sign chorevma (χόρευμα, Νο.

Manuel Chrysaphes wrote about this resolution of phthora nenano: Εἰ δὲ διὰ δεσμὸν τέθειται ἡ φθορὰ αὕτη, γίνεται οὕτως.

[45] The beginning of this section emphasizes the tetraphonic melos of the diatonic echos varys, its characteristic is the tritone above the finalis within the tritos pentachord F, and the word "τετράφωνος" has the cadence formula of ἦχος βαρύς.

In a second step the lower octave on the phthongos G changes from the heptaphonic tone system of tetartos to the triphonic one of phthora nana, which places the finalis G as the connection between two tetrachords (D—E—F#—G—a—b natural—c) as it was taught by the "parallage of Ioannes Plousiadinos".

60) was integrated by Petros Peloponnesios, but as mesos devteros in the soft chromatic genos which corrects the change to the triphonia of the great sign phthora ("φθορά", No.

Some of his heirmologic compositions like Πασᾶν τὴν ἐλπίδα μοῦ use several makam models for extravagant changes between different echoi, at least in the later transcriptions according to the New Method and its "exoteric phthorai".

During the 18th century, models dedicated to a certain makam (seyirler) were already collected in the manuscript by Kyrillos Marmarinos and were later organized according to the Octoechos order like the great signs in the mathema "Mega Ison".

An example is the edition of Panagiotes Keltzanides' "Methodical teaching of the theory and practice for the instruction and the dissemination of the genuine external music" which was published in 1881.

[52] The seventh chapter of Keltzanides' book contains an introduction into all the "exoteric phthorai" of the New Method used for more than 40 makamlar ordered according to the Octoechos and the Turkish fret name of the basis tone.