Medieval hunting

The biography of the Merovingian noble Saint Hubert of Liège (died 727/728) recounts how hunting could become an obsession.

Here the peasantry could not hunt, poaching being subject to severe punishment: the injustice of such "emparked" preserves was a common cause of complaint in populist vernacular literature.

The lower classes mostly had to content themselves with snaring birds and smaller game outside of forest reserves and warrens.

Knowledge and (partly whimsical) extension of this terminology became a courtly fashion in the 14th century in France and England.

Medieval books of hunting laid huge stress on the importance of correct terminology, a tradition which was further extended to great lengths in the Renaissance period.

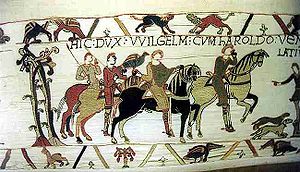

[2][3] The invention of the "fair terms" of hunting was attributed by Malory and others to the Arthurian knight Sir Tristram,[4][page needed] who is seen both as the model of the noble huntsman, and the originator of its ritual: As he [Sir Tristram] grew in power and strength he laboured in hunting and hawking – never a gentleman that we ever heard of did more.

(Modernised) English and French accounts agree on the general makeup of a hunt—they were well-planned so that everyone knew his role before going out.

Gaston, Duke of Orleans, argued against hunters taking game in more efficient ways such as by bow and arrow or by setting traps, saying, "I speak of this against my will, for I should only teach how to take beasts nobly and gently" ("mes de ce parle je mal voulentiers, quar je ne devroye enseigner a prendre les bestes si n'est par noblesce et gentillesce").

Boys at the age of 7 or 8 years began to learn how to handle a horse, travel with a company in forests, and utilize a weapon, practicing these skills in hunting groups.

As a result, young men in the nobility and royalty were able to transfer acquired skills such as horsemanship, weapons management, wood-crafting, terrain assessment, and strategy formation from the hunting grounds to the battlefield in wars.

There were cart- and packhorses employed in the day-to-day work of the household, palfreys used for human transport, and destriers, or warhorses, a powerful and expensive animal that in late medieval England could obtain prices of up to £80.

The courser, though inferior to the destrier and much smaller than today's horses, still had to be powerful enough to carry the rider at high speeds over large distances, agile, so it could maneuver difficult terrain without difficulty, and fearless enough not to be scared when encountering wild beasts.

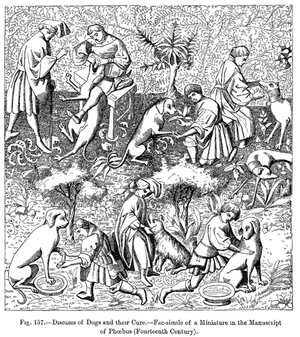

Furthermore, greyhounds, though aggressive hunters, were valued for their docile temper at home, and often allowed inside as pets.

Handled on a long leash, the lymer would be used to find the lay of the game before the hunt even started, and it was therefore important that, in addition to having a good nose, it remained quiet.

Though this might seem harsh by modern standards, the warm dog house could often be much more comfortable than the sleeping quarters of other medieval servants.

Falconry, a common activity in the Middle Ages, was the training of falcons and hawks for personal usage, which included hunting game.

King Frederick II considered them the best "out of respect to their size, strength, audacity, and swiftness".

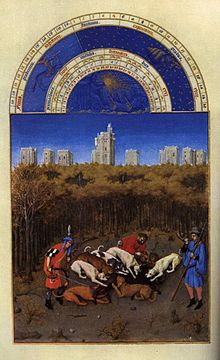

Par force hunting consisted of eight parts: the quest, the assembly, the relays, the moving or un-harboring, the chase, the baying, the unmaking and the curée.

It was often compared to Christ for its suffering; a well-known story tells of how St. Eustace was converted to Christianity by seeing a crucifix between the antlers of a stag while hunting.

Other stories told of how the hart could become several hundred years old, and how a bone in the middle of its heart prevented it from dying of fear.

In 1015 for example, the Doge Ottone Orseolo demanded for himself and his successors the head and feet of every boar killed in his area of influence.

[9] The boar was a highly dangerous animal to hunt; it would fight ferociously when under attack, and could easily kill a dog, a horse, or a man.

It was hunted par force, and when at bay, a hound like a mastiff could perhaps be foolhardy enough to attack it, but ideally it should be killed by a rider with a spear.

Pelts were the only considered practical use for wolves, and were usually made into cloaks or mittens, though not without hesitation, due to the wolf's foul odour.

There were generally no restrictions or penalties in the civilian hunting of wolves, except in royal game reserves, under the reasoning that the temptation for an intruding commoner to shoot a deer there was too great.

[13] Before its extinction in the British Isles, the wolf was considered by the English nobility as one of the five so called "Royal Beasts of the Chase".

[citation needed] Some animals were considered inedible, but still hunted for the sport, such as foxes, otters or badgers.

There is a recorded instance of St Thomas Becket performing a miracle by healing a forester shot in the throat by poachers.

Religious symbolism was common; the hart or the unicorn was often associated with Christ, but the hunt itself could equally be seen as the Christian's quest for truth and salvation.

In the more secular literature, romances for instance, the hunter pursuing his quarry was often used as a symbol of the knight's struggle for his lady's favor.