Paracelsus

[17] Paracelsus was born in Egg an der Sihl [de],[18] a village close to the Etzel Pass in Einsiedeln, Schwyz.

His father Wilhelm (d. 1534) was a chemist and physician, an illegitimate descendant of the Swabian noble Georg [de] Bombast von Hohenheim (1453–1499), commander of the Order of Saint John in Rohrdorf.

His wanderings led him from Italy to France, Spain, Portugal, England, Germany, Scandinavia, Poland, Russia, Hungary, Croatia, Rhodes, Constantinople, and possibly even Egypt.

[27][28][29] During this period of travel, Paracelsus enlisted as an army surgeon and was involved in the wars waged by Venice, Holland, Denmark, and the Tatars.

At that time, Basel was a centre of Renaissance humanism, and Paracelsus here came into contact with Erasmus of Rotterdam, Wolfgang Lachner, and Johannes Oekolampad.

He published harsh criticism of the Basel physicians and apothecaries, creating political turmoil to the point of his life being threatened.

On 23 June 1527, he burnt a copy of Avicenna's Canon of Medicine, an enormous tome that was a pillar of academic study, in market square.

[31] During his time as a professor at the University of Basel, he invited barber-surgeons, alchemists, apothecaries, and others lacking academic background to serve as examples of his belief that only those who practised an art knew it: "The patients are your textbook, the sickbed is your study.

[41] The great medical problem of this period was syphilis, possibly recently imported from the West Indies and running rampant as a pandemic completely untreated.

He finally managed to publish his Die grosse Wundartznei ("The Great Surgery Book"), printed in Ulm, Augsburg, and Frankfurt in this year.

His works were frequently reprinted and widely read during the late 16th to early 17th centuries, and although his "occult" reputation remained controversial, his medical contributions were universally recognized: a 1618 pharmacopeia by the Royal College of Physicians in London included "Paracelsian" remedies.

[44] The late 16th century saw substantial production of Pseudo-Paracelsian writing, especially letters attributed to Paracelsus, to the point where biographers find it impossible to draw a clear line between genuine tradition and legend.

[45] As a physician of the early 16th century, Paracelsus held a natural affinity with the Hermetic, Neoplatonic, and Pythagorean philosophies central to the Renaissance, a world-view exemplified by Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola.

Because of this, when the Earth and the Heavens eventually dissipate, the virtues of all natural objects will continue to exist and simply return to God.

[48] Paracelsus was one of the first medical professors to recognize that physicians required a solid academic knowledge in the natural sciences, especially chemistry.

[51] Paracelsus in the beginning of the sixteenth century had unknowingly observed hydrogen as he noted that in reaction when acids attack metals, gas was a by-product.

[58] Paracelsus also believed that mercury, sulphur, and salt provided a good explanation for the nature of medicine because each of these properties existed in many physical forms.

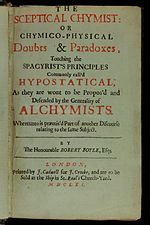

Nor has an Hypothesis so ... maturely established been called in Question till in the last Century Paracelsus and some ... Empiricks, rather then ... Philosophers ... began to rail at the Peripatetick Doctrine ... and to tell the credulous World, that they could see but three Ingredients in mixt Bodies ... instead of Earth, and Fire, and Vapour, Salt, Sulphur, and Mercury; to which they gave the canting title of Hypostatical Principles: but when they came to describe them ...’tis almost ... impossible for any sober Man to find their meaning.

[69] Paracelsus invented, or at least named a sort of liniment, opodeldoc, a mixture of soap in alcohol, to which camphor and sometimes a number of herbal essences, most notably wormwood, were added.

[51] The dominant medical treatments in Paracelsus's time were specific diets to help in the "cleansing of the putrefied juices" combined with purging and bloodletting to restore the balance of the four humours.

The following prescription by Paracelsus was dedicated to the village of Sterzing: Also sol das trank gemacht werden, dadurch die pestilenz im schweiss ausgetrieben wird: (So the potion should be made, whereby the pestilence is expelled in sweat:) eines guten gebranten weins...ein moß, (Medicinal brandy) eines guten tiriaks zwölf lot, (Theriac) myrrhen vier lot, (Myrrh) wurzen von roßhuf sechs lot, (Tussilago sp.)

(Camphor) Dise ding alle durch einander gemischet, in eine sauberes glas wol gemacht, auf acht tag in der sonne stehen lassen, nachfolgents dem kranken ein halben löffel eingeben... (Mix all these things together, put them into a clean glass, let them stand in the sun for eight days, then give the sick person half a spoonful...) One of his most overlooked achievements was the systematic study of minerals and the curative powers of alpine mineral springs.

"[77] Paracelsus called for the humane treatment of the mentally ill as he saw them not to be possessed by evil spirits, but merely 'brothers' ensnared in a treatable malady.

Above and below the image are the mottos Alterius non sit qui suus esse potest ("Let no man belong to another who can belong to himself") and Omne donum perfectum a Deo, inperfectum a Diabolo ("All perfect gifts are from God, [all] imperfect [ones] from the Devil"); later portraits give a German rendition in two rhyming couplets (Eines andern Knecht soll Niemand sein / der für sich bleiben kann allein /all gute Gaben sint von Got / des Teufels aber sein Spot).

[78] Posthumous portraits of Paracelsus, made for publications of his books during the second half of the 16th century, often show him in the same pose, holding his sword by its pommel.

The so-called "Rosicrucian portrait", published with Philosophiae magnae Paracelsi (Heirs of Arnold Birckmann, Cologne, 1567), is closely based on the 1540 portrait by Hirschvogel (but mirrored, so that now Paracelsus's left hand rests on the sword pommel), adding a variety of additional elements: the pommel of the sword is inscribed by Azoth, and next to the figure of Paracelsus, the Bombast von Hohenheim arms are shown (with an additional border of eight crosses patty).

Paracelsus was especially venerated by German Rosicrucians, who regarded him as a prophet, and developed a field of systematic study of his writings, which is sometimes called "Paracelsianism", or more rarely "Paracelsism".

[81] The prophecies contained in Paracelsus's works on astrology and divination began to be separately edited as Prognosticon Theophrasti Paracelsi in the early 17th century.

His prediction of a "great calamity just beginning" indicating the End Times was later associated with the Thirty Years' War, and the identification of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden as the "Lion from the North" is based in one of Paracelsus's "prognostications" referencing Jeremiah 5:6.

Paracelsus is the main character of Jorge Luis Borges's short story "La rosa de Paracelso" (anthologized in Shakespeare's Memory, 1983).