Parallel (geometry)

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, a line and a plane that do not share a point are also said to be parallel.

[7] Alternative definitions were discussed by other Greeks, often as part of an attempt to prove the parallel postulate.

Simplicius also mentions Posidonius' definition as well as its modification by the philosopher Aganis.

[7] At the end of the nineteenth century, in England, Euclid's Elements was still the standard textbook in secondary schools.

A major difference between these reform texts, both between themselves and between them and Euclid, is the treatment of parallel lines.

Lewis Carroll), wrote a play, Euclid and His Modern Rivals, in which these texts are lambasted.

[9] One of the early reform textbooks was James Maurice Wilson's Elementary Geometry of 1868.

[10] Wilson based his definition of parallel lines on the primitive notion of direction.

Dodgson also devotes a large section of his play (Act II, Scene VI § 1) to denouncing Wilson's treatment of parallels.

[13] Other properties, proposed by other reformers, used as replacements for the definition of parallel lines, did not fare much better.

The main difficulty, as pointed out by Dodgson, was that to use them in this way required additional axioms to be added to the system.

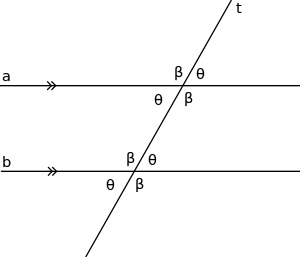

The three properties above lead to three different methods of construction[15] of parallel lines.

Equivalently, they are parallel if and only if the distance from a point P on line m to the nearest point in plane q is independent of the location of P on line m. Similar to the fact that parallel lines must be located in the same plane, parallel planes must be situated in the same three-dimensional space and contain no point in common.

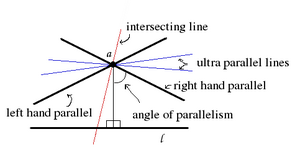

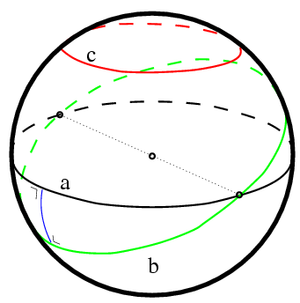

In non-Euclidean geometry, the concept of a straight line is replaced by the more general concept of a geodesic, a curve which is locally straight with respect to the metric (definition of distance) on a Riemannian manifold, a surface (or higher-dimensional space) which may itself be curved.

In general geometry the three properties above give three different types of curves, equidistant curves, parallel geodesics and geodesics sharing a common perpendicular, respectively.

However, in case l = n, the superimposed lines are not considered parallel in Euclidean geometry.

In the study of incidence geometry, this variant of parallelism is used in the affine plane.