Paris in the 18th century

Paris witnessed the end of the reign of Louis XIV, was the center stage of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, saw the first manned flight, and was the birthplace of high fashion and the modern restaurant and bistro.

The Comédie-Italienne theater company had been banned from Paris in 1697 for presenting a thinly disguised satire about the King's wife, Madame de Maintenon, called La Fausse Prude.

He played on the terrace of the Tuileries Garden, had his own private zoo, and a room filled with scientific instruments telescopes, microscopes, compasses, mirrors, and models of the planets, where he was instructed by members of the Academy of Sciences.

The site selected was the marshy open space between the Seine, the moat and bridge to the Tuileries garden, and the Champs-Élysées, which led to the Étoile, convergence of hunting trails on the western edge of the city (now Place Charles de Gaulle-Étoile).

[28] The indigent, those who were unable to support themselves, were numerous, and largely depended upon religious charity or public assistance to survive such as the philanthropic activities organized by Queen Marie Leczinska (Wife of Louis XV) who from her carriages personally gave money and clothes for the poor on her regular visits to the capital.

wood carvers, and foundries of Paris were kept busy making luxury furnishings, statues, gates, door knobs, ceilings, and architectural ornament for the royal palaces and for the new town houses of the nobility in the Faubourg Saint-Germain.

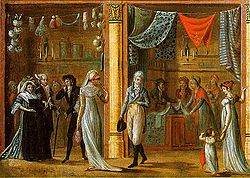

[33] The most prominent name in fashion was Rose Bertin, who made dresses for Marie Antoinette; in 1773 she opened a shop called the Grand Mogol on the Faubourg rue Saint-Honoré that catered to the wealthiest and most fashion-conscious Parisians.

[37] On August 10, 1792, on the same day that the members of the more radical political clubs and the sans-culottes stormed the Tuileries Palace, they also took over the Hotel de Ville, expelling the elected government and an Insurrectionary Commune.

While the University vanished, new military science and engineering teaching schools flourished during the Revolution, as the revolutionary government sought to create a highly centralized and secular education system, centered in Paris.

[64] There was no public transportation in Paris in the 18th century; the only way for ordinary Parisians to move around the city was on foot, a difficult experience in the winding, crowded and narrow streets, especially in the rain or at night.

These were large private gardens where, in summer, Parisians paid an admission charge and found food, music, dancing, and other entertainment, from pantomime to magic lantern shows and fireworks.

It contained a miniature Egyptian pyramid, a Roman colonnade, antique statues, a pond of water lilies, a tatar tent, a farmhouse, a Dutch windmill, a temple of Mars, a minaret, an Italian vineyard, an enchanted grotto, and "a gothic building serving as a chemistry laboratory," as described by Carmontelle.

It was followed by Le Mariage de Figaro, which was accepted for production by the management of the Comédie Française in 1781, but at private reading before the French court the play so shocked King Louis XVI that he forbade its public presentation.

Other notable painters, including Maurice Quentin de la Tour, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Joseph Vernet and Jean-Honoré Fragonard came to Paris from the provinces and achieved success.

The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau described his disappointment when he first arrived in Paris in 1731: I expected a city as beautiful as it was grand, of an imposing appearance, where you saw only superb streets, and palaces of marble and gold.

Instead, when I entered by the Faubourg Saint-Marceau, I saw only narrow, dirty and foul-smelling streets, and villainous black houses, with an air of unhealthiness; beggars, poverty; wagons-drivers, menders of old garments; and vendors of tea and old hats.

"[94] Louis XVI had ascended the throne of France in 1774, and his new government in Versailles desperately needed money; the treasury had been drained by the Seven Years' War (1755–63) and the French intervention in the American Revolution.

A trade agreement with England in 1786 allowed British manufactured goods to enter France with low tariffs; as a result, many Parisian workers, particularly in the new textile industry, lost their jobs.

The radical Jacobins had their headquarters in the former convent of the Dominicans on Rue Saint-Honoré, near the meeting place of the National Assembly in the manege of the Tuileries Palace, and the home of its most famous member, Robespierre.

The guillotine was moved to the edge of the city, at the Barrière du Trône, farther from the public eye, and the pace of executions accelerated to as many as fifty a day; the cadavers were buried in common graves on rue de Picpus.

[119] On June 8, 1794, at the debut of the new wave of terror, Robespierre presided over the Festival of the Supreme Being in the huge amphitheater on the Champs de Mars which had been constructed in 1790 for the first anniversary of the Revolution; the ceremony was designed by the painter David, and featured a ten-hour parade, bonfires a statue of wisdom, and a gigantic mountain with a tree of liberty at the peak.

Early in the morning of 28 July, policemen and members of the National Guard summoned by the Convention invaded the Hôtel de Ville and arrested Robespierre and his twenty-one remaining supporters.

The life of ordinary Parisians was extremely difficult, due to a very cold winter in 1794–95, there were shortages and long lines for bread, firewood, charcoal meat, sugar, coffee, vegetables and wine.

[122] The shortages led to unrest; on 1 April 1795 a crowd of Parisians, including many women and children, invaded the meeting hall of the Convention, demanding bread and the return of the old revolutionary government.

The first column on Quai Voltaire was met by a young general of artillery, Napoleon Bonaparte, who had placed cannon on the opposite side of the river at the gates of the Louvre and the head of the Pont de la Concorde.

A businessman named Liardot rented a large former mansion, brought in selected eligible young women as paying guests, and invited men seeking wives to meet them at balls, concerts and card games each given at the house each evening.

These were largely upper middle class young men, numbering between and two and three thousand, who dressed in an extravagant fashion, spoke with an exaggerated accent, carried canes as weapons, and, particularly in 1794 and 1795, they patrolled the streets in groups and attacked sans culottes and symbols of the revolution.

Some of the former palatial townhouses of the nobility were rented and used for ballrooms; the Hotel Longueville put on enormous spectacles, with three hundred couples dancing, in thirty circles of sixteen dancers each, the women in nearly transparent consumes, styled after Roman togas.

The Pavillon de Hannovre, formerly part of the residential complex of Cardinal Richelieu, featured a terrace for dancing and dining decorated with Turkish tents, Chinese kiosks and lanterns.

Beside Méot and Beauvilliers, the Palais-Royal had the restaurants Naudet, Robert, Very, Foy and Huré, and the Cafés Berceau, Lyrique, Liberté Conquise, de Chartres, and du Sauvage (the last owned by the former coachman of Robespierre).