Paris under Napoleon

The Louvre became the Napoleon Museum, in a wing of the former palace, displaying many works of art he brought back from his military campaigns in Italy, Austria, Holland and Spain; and he militarized and re-organized the Grandes écoles, to train engineers and administrators.

They were joined by a new aristocracy created by Napoleon, consisting of his generals, ministers and courtiers, as well as bankers, industrialists, and those who furnished military supplies; about three thousand persons altogether.

[10] According to one account from 1814, they had their own social hierarchy; the courtesans at the top, whose clients were exclusively the noble or wealthy; then a class composed of actresses, dancers, and those from the theater world; then semi-respectable prostitutes from the middle class who sometimes received clients at home, often with the husband's consent; then unemployed or working-women who needed money, down to the lowest level, who were found in the city's worst neighborhoods, the Port du Blé, the rue Purgée, and rue Planche Mibray.

Claude Lachaise, in his Topographie médicale de Paris (1822), described a "bizarre assembly of buildings badly constructed, collapsing, damp and dark, each one occupied by twenty-nine or thirty persons, the largest number of whom are masons, iron workers, water-carriers, and street merchants ...the problems are increased by the small size of the rooms, the narrowness of the doors and windows, the multiplicity of families or households, which can reach ten in a single house, and by the influx of poor who are attracted by the low prices of the housing."

This system never really functioned and was suppressed by the French Directory, which eliminated the position of Mayor and divided Paris into twelve separate municipalities, whose leaders were selected by the national government.

A new law on 17 February 1800 modified the system; Paris became a single commune, divided into twelve arrondissements, each with its own mayor, once again chosen by Napoleon and the national government.

Napoleon and Marie-Louise escaped unharmed, but the wife of the Austrian Ambassador and the Princess de la Leyen were killed, and a dozen other guests died later from their burns.

Napoleon issued a decree on September 18, 1811 which militarized the firemen into a battalion of sapeur-pompiers, with four companies of one hundred forty-two men each, under the Prefect of Police and the Ministry of the Interior.

Napoleon created a Health Council under the Prefect of Police to monitor the safety of the water supply, food products, and the environmental effects of new factories and workshops.

Napoleon also made efforts to improve the health of the city, by building a canal to provide fresh water and by constructing sewers under the streets that he built, but their effects were limited.

[28] Napoleon made an effort to improve the traffic circulation in the heart of the city by creating new streets; in 1802, on the land of the former convents of the Assumption and the Capucins, he built rue du Mont-Thabor.

To the west he constructed the Pont d'Iéna, (1808–1814) which linked the large parade ground of the École Militaire on the left bank with the hill of Chaillot, where he intended to build a palace for his son, the King of Rome.

[33] On July 15, 1801, Napoleon signed a Concordat with the Pope, which allowed the thirty-five surviving parish churches and two hundred chapels and other religious institutions of Paris to reopen.

[39] The 14th of July 1800. the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, a solemn holiday after the Revolution, was transformed into the Festival of Concord and Reconciliation, and into a celebration of the Emperor's victory at the Battle of Marengo one month earlier.

It marked the birthday of the Emperor, the Catholic festival of the Assumption, and the anniversary of the Concordat, signed by Napoleon and the Pope on that day in 1801, which allowed the churches of France to reopen.

[39] It was almost impossible to walk in the narrow streets of Paris, due to the mud and traffic, and the Champs-Élysées did not yet exist, so upper and middle class Parisians took their promenades on the grand boulevards, in the public and private parks and gardens, and above all in the Palais-Royal.

The arcades of the Palais-Royal, as described by the German traveler Berkheim in 1807, contained boutiques with glass show windows displaying jewelry, fabrics, hats, perfumes, boots, dresses, paintings, porcelain, watches, toys, lingerie, and every type of luxury goods.

[42] The most best-known landmarks on the boulevards were the Café Hardi, at rue Cerutti, where businessmen gathered, the Café Chinois and Pavillon d'Hannover, a restaurant and bath house in the form of a Chinese temple; and Frascati's at the corner of rue Richelieu and boulevard Montmartre, famous for its ice creams, elegant furnishings and its garden, where in summer, according to Berkheim, gathered "the most elegant and beautiful women of Paris."

[42] Pleasure gardens were a popular form of entertainment for the middle and upper classes, where, for an admission charge of twenty sous, visitors could sample ice creams, see pantomimes, acrobatics and jugglers, listen to music, dance, or watch fireworks.

[48] Women's fashion during the Empire was set to a large degree by the Empress Joséphine de Beauharnais and her favorite designer, Hippolyte Leroy, who was inspired by the Roman statues of the Louvre and the frescoes of Pompeii.

The antique Roman style, introduced during the Revolution, continued to be popular but was modified because Napoleon disliked immodesty in women's clothing; low necklines and bare arms were banned.

For students in the Left Bank, there were restaurants like Flicoteau, on rue de la Parcheminerie, which had no tablecloths or napkins, where diners ate at long tables with benches, and the menu consisted of bowls of bouillon with pieces of meat.

Eighteen months later, with the signing of the Concordat between Napoleon and the Pope, churches were allowed to hold mass, ring their bells, and priests could appear in their religious attire on the streets.

About eighteen hundred students, mostly from the most wealthy and influential families, attended the four most famous lycées in Paris in 1809; the Imperial (now Louis le Grand); Charlemagne; Bonaparte (now Condorcet); and Napoléon (now Henry IV).

The stars of the salon were the history painters, Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, Antoine-Jean Gros, Jacques-Louis David, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson and Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, who painted large canvases of the events of the Empire and the heroes and heroines of ancient Rome.

David removed her from his work The Distribution of the Eagles, leaving an empty space; the painter Jean-Baptiste Regnault, however, refused to take her out of his painting of the wedding of Jérôme Bonaparte.

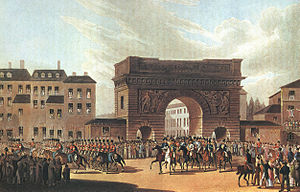

[63] In January 1814, after Napoleon's decisive defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, the Allied armies of Austria, Prussia and Russia, with over five hundred thousand men, invaded France and headed for Paris.

[68] Paris was occupied by Prussian, Russian, Austrian and British soldiers, who camped in the Bois de Boulogne and the open land along the Champs Élysées, and remained for several months, while the King restored the royal government and replaced Bonapartists with his own ministers, many of whom returned from exile with him.

The discontent of the Parisians grew as the new government, following the guidance of the new religious authorities named by the King, required all shops and markets to close and banned any sort of entertainment or leisure activities on Sundays.

He resumed work on several of his unfinished projects, including the Elephant fountain at the Bastille, a new market at Saint-Germain, the foreign ministry building at the Quai d'Orsay and a new wing of the Louvre.