Parthenon

Based on literary and historical research, he proposes that "the treasury called the Parthenon should be recognized as the west part of the building now conventionally known as the Erechtheion".

[citation needed] Some scholars, therefore, argue that the Parthenon should be viewed as a grand setting for a monumental votive statue rather than as a cult site.

[40][41] She argues a pedagogical function for the Parthenon's sculptured decoration, one that establishes and perpetuates Athenian foundation myth, memory, values and identity.

[42][43] While some classicists, including Mary Beard, Peter Green, and Garry Wills[44][45] have doubted or rejected Connelly's thesis, an increasing number of historians, archaeologists, and classical scholars support her work.

[50] The first endeavour to build a sanctuary for Athena Parthenos on the site of the present Parthenon was begun shortly after the Battle of Marathon (c. 490–488 BC) upon a solid limestone foundation that extended and levelled the southern part of the Acropolis summit.

This picture was somewhat complicated by the publication of the final report on the 1885–1890 excavations, indicating that the substructure was contemporary with the Kimonian walls, and implying a later date for the first temple.

One difficulty in dating the proto-Parthenon is that at the time of the 1885 excavation, the archaeological method of seriation was not fully developed; the careless digging and refilling of the site led to a loss of much valuable information.

[59] This inspired American archaeologist William Bell Dinsmoor to give limiting dates for the temple platform and the five walls hidden under the re-terracing of the Acropolis.

The most important buildings visible on the Acropolis today – the Parthenon, the Propylaia, the Erechtheion and the temple of Athena Nike – were erected during this period.

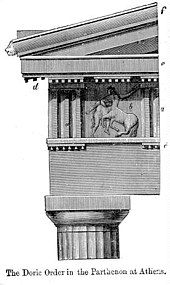

Above the architrave of the entablature is a frieze of carved pictorial panels (metopes), separated by formal architectural triglyphs, also typical of the Doric order.

John Julius Cooper wrote that "even in antiquity, its architectural refinements were legendary, especially the subtle correspondence between the curvature of the stylobate, the taper of the naos walls, and the entasis of the columns".

The metopes of the east side of the Parthenon, above the main entrance, depict the Gigantomachy (the mythical battle between the Olympian gods and the Giants).

[9] The mythological figures of the metopes of the East, North, and West sides of the Parthenon had been deliberately mutilated by Christian iconoclasts in late antiquity.

The experts discovered the metopes while processing 2,250 photos with modern photographic methods, as the white Pentelic marble they are made of differed from the other stone of the wall.

[86] Joan Breton Connelly offers a mythological interpretation for the frieze, one that is in harmony with the rest of the temple's sculptural programme which shows Athenian genealogy through a series of succession myths set in the remote past.

The great procession marching toward the east end of the Parthenon shows the post-battle thanksgiving sacrifice of cattle and sheep, honey and water, followed by the triumphant army of Erechtheus returning from their victory.

This belief emerges from the fluid character of the sculptures' body position which represents the effort of the artist to give the impression of a flowing river.

[96] Every statue on the west pediment has a fully completed back, which would have been impossible to see when the sculpture was on the temple; this indicates that the sculptors put great effort into accurately portraying the human body.

Thanks to him, Western Europe was able to have the first design of the monument, which Ciriaco called "temple of the goddess Athena", unlike previous travellers, who had called it "church of Virgin Mary":[115] ...mirabile Palladis Divae marmoreum templum, divum quippe opus Phidiae ("...the wonderful temple of the goddess Athena, a divine work of Phidias").

In 1456, Ottoman Turkish forces invaded Athens and laid siege to a Florentine army defending the Acropolis until June 1458, when it surrendered to the Turks.

[118][119] The precise circumstances under which the Turks appropriated it for use as a mosque are unclear; one account states that Mehmed II ordered its conversion as punishment for an Athenian plot against Ottoman rule.

[124] In 1667, the Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi expressed marvel at the Parthenon's sculptures and figuratively described the building as "like some impregnable fortress not made by human agency".

[101] These depictions, particularly Carrey's, provide important, and sometimes the only, evidence of the condition of the Parthenon and its various sculptures prior to the devastation it suffered in late 1687 and the subsequent looting of its art objects.

The Ottomans fortified the Acropolis and used the Parthenon as a gunpowder magazine – despite having been forewarned of the dangers of this use by the 1656 explosion that severely damaged the Propylaea – and as a shelter for members of the local Turkish community.

[132] The 18th century was a period of Ottoman stagnation—so that many more Europeans found access to Athens, and the picturesque ruins of the Parthenon were much drawn and painted, spurring a rise in philhellenism and helping to arouse sympathy in Britain and France for Greek independence.

Amongst those early travellers and archaeologists were James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, who were commissioned by the Society of Dilettanti to survey the ruins of classical Athens.

From 1801 to 1812, agents of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, removed about half the surviving Parthenon sculptures, sending them to Britain in efforts to establish a private museum.

[135][136] When independent Greece gained control of Athens in 1832, the visible section of the minaret was demolished; only its base and spiral staircase up to the level of the architrave remain intact.

In the later 19th century, the Parthenon was widely considered by Americans and Europeans to be the pinnacle of human architectural achievement, and became a popular destination and subject of artists, including Frederic Edwin Church and Sanford Robinson Gifford.

[139][140] Today it attracts millions of tourists every year, who travel up the path at the western end of the Acropolis, through the restored Propylaea, and up the Panathenaic Way to the Parthenon, which is surrounded by a low fence to prevent damage.