Particle physics

They occur after collisions between particles made of quarks, such as fast-moving protons and neutrons in cosmic rays.

The dominant theory explaining these fundamental particles and fields, along with their dynamics, is called the Standard Model.

The two are closely interrelated: the Higgs boson was postulated by theoretical particle physicists and its presence confirmed by practical experiments.

The idea that all matter is fundamentally composed of elementary particles dates from at least the 6th century BC.

[1] In the 19th century, John Dalton, through his work on stoichiometry, concluded that each element of nature was composed of a single, unique type of particle.

Bethe's 1947 calculation of the Lamb shift is credited with having "opened the way to the modern era of particle physics".

Important discoveries such as the CP violation by James Cronin and Val Fitch brought new questions to matter-antimatter imbalance.

[5][6] The current state of the classification of all elementary particles is explained by the Standard Model, which gained widespread acceptance in the mid-1970s after experimental confirmation of the existence of quarks.

On 4 July 2012, physicists with the Large Hadron Collider at CERN announced they had found a new particle that behaves similarly to what is expected from the Higgs boson.

This causes the fermions to obey the Pauli exclusion principle, where no two particles may occupy the same quantum state.

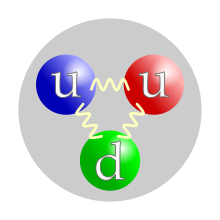

[21] The strong interaction is mediated by the gluon, which can link quarks together to form composite particles.

[citation needed] Quarks and gluons additionally have color charges, which influences the strong interaction.

[17] The gluon can have eight color charges, which are the result of quarks' interactions to form composite particles (gauge symmetry SU(3)).

Quarks inside hadrons are governed by the strong interaction, thus are subjected to quantum chromodynamics (color charges).

[34] The graviton is a hypothetical particle that can mediate the gravitational interaction, but it has not been detected or completely reconciled with current theories.

Theorists make quantitative predictions of observables at collider and astronomical experiments, which along with experimental measurements is used to extract the parameters of the Standard Model with less uncertainty.

This work probes the limits of the Standard Model and therefore expands scientific understanding of nature's building blocks.

Those efforts are made challenging by the difficulty of calculating high precision quantities in quantum chromodynamics.

[48][49] It may involve work on supersymmetry, alternatives to the Higgs mechanism, extra spatial dimensions (such as the Randall–Sundrum models), Preon theory, combinations of these, or other ideas.

[citation needed] In principle, all physics (and practical applications developed therefrom) can be derived from the study of fundamental particles.

In practice, even if "particle physics" is taken to mean only "high-energy atom smashers", many technologies have been developed during these pioneering investigations that later find wide uses in society.

[52] Major efforts to look for physics beyond the Standard Model include the Future Circular Collider proposed for CERN[53] and the Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel (P5) in the US that will update the 2014 P5 study that recommended the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, among other experiments.

β −

decay , showing a neutron (n, udd) converted into a proton (p, udu). "u" and "d" are the up and down quarks , "

e −

" is the electron , and "

ν

e " is the electron antineutrino .