Hypothetical partition of Belgium

The crisis over the formation of a coalition government in the aftermath of the 2007 elections, coupled with the unsolved problem of the Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde electoral district and the rise of extremist political parties, has given a fresh impetus to the issue, with recent opinion polls showing sizable support for a partition.

The Low Countries emerged at the end of the Middle Ages as a very loose political confederation of fiefdoms ruled in personal union by the House of Habsburg: the Seventeen Provinces.

In 1815, the territory now constituting Belgium was incorporated into the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, which had been created to rehabilitate and consolidate the former Seventeen Provinces and serve as a buffer against any expansionist ambitions of France.

[16] Major European powers (which included France, Prussia and the United Kingdom) were divided over their response to the revolution of the Belgian people against the Dutch royal authorities.

However, this plan was rejected as absurd by the French ambassador to the United Kingdom, Talleyrand, who cited the danger posed by a British base on the European mainland.

The Voeren have a long Flemish tradition and, in the Land of Herve, several communes which used to use Germanic dialects switched to French during the 18th century, as for example, Berneau and Warsage, both now part of Dalhem and Saint-Jean-Sart, a hamlet of Aubel.

[24] Several sovereigns of the region, notably including Maria Theresa of Austria, succeeded in making French not only the language of the court but also of their administrations.

The government's long refusal to acknowledge Dutch as an official language led to hostilities between Flanders and the French-speaking bourgeoisie who held both political and economic power.

While the N-VA seeks greater autonomy and favours the independence of Flanders, possibly in a confederate state,[33] the Vlaams Belang is more clearly separatist.

French-speaking politicians (who were sometimes elected in Flanders) and other influential citizens opposed the Flemish demands for the recognition of Dutch and wished to maintain a centralized government to prevent regionalization.

On the other hand, the Walloon politician Jules Destrée reacted in 1912 to the process of minorisation of Wallonia and asked explicitly for a splitting of Belgium along linguistic lines.

One is a more regional Walloon movement, demanding to maintain the solidarity between the richer north and the poorer south, but also increasingly stressing the separate cultural identity of Wallonia.

Flemish nationalists have claimed that the French-speaking "Belgicists" of Brussels and its suburbs do not have common interests with the Walloons, but that these two parties have formed a quid-pro-quo alliance to oppose the Dutch-speaking majority.

Ethnic tensions affect the working of local governments, which often pass laws prohibiting the use of the language of the respective minority populations in official functions.

On the other hand, Dutch-speaking citizens of the Flemish municipalities close to Brussels claim their position is being undermined by the minority rights of French-speaking settlers.

Significant pressures in living conditions have kept the two main communities separate and confined to their majority regions; stark ethnic and linguistic segregation has emerged in Brussels, the capital and largest city of the country.

[41] The possible status of Brussels as a "city-state" has been suggested by Charles Picqué, Minister-President of the Brussels-Capital Region, who sees a tax on the EU institutions as a way of enriching the city.

Prior to its dissolution, this district was the last remaining entity in Belgium that did not coincide with provincial borders, and as such had been deemed unconstitutional by the Belgian Constitutional Court.

[43] Four theoretical scenarios are usually considered in the event that a partition of Belgium would occur: remaining with Wallonia, sovereign statehood, reattachment to Germany, or attachment to Luxembourg.

This status quo solution is the most probable, although it is uncertain whether or not the German-speakers could maintain their cultural and political rights in the long term in an otherwise monolingual francophone country.

[45] In particular, on September 6, 2010, after long lasting negotiation for the formation of the federal government, most leaders of the French-speaking Socialist Party simultaneously declared that they now consider the partition of Belgium as a realistic alternative solution to the Belgian problems.

In particular the N-VA and a part of the Flemish movement want to apply the so-called Maddens Doctrine in order to enforce the Francophones to require such a state reform.

The Francophone Socialist Party (PS) and Christian democrats (cdH) promote the conservation of the current Belgian welfare state, and therefore oppose any further regionalisation of the federal social policies.

N-VA does not openly advocate the partition of Belgium, instead proposing a confederalist solution, where the center of power would shift to the regional governments, while certain tasks such as e.g. the army, diplomacy or the national football competition would remain on the Belgian level.

While prime minister Guy Verhofstadt's lame duck ministry remained in power as caretaker, several leading politicians were nominated without success by the King[64] to build a stable governmental coalition.

In December 2008, another crisis related to the Fortis case, erupted, again destabilising the country and resulting in the resignation of Belgian Prime Minister Yves Leterme.

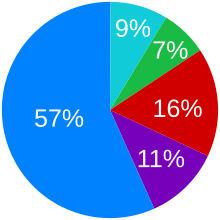

Although most Flemish political parties describe their demands as limited to seeking greater regional autonomy and decentralization of government (save for members of the Vlaams Belang party,[18] who called for a splitting of the country and claim of a national identity, culture and institutions, as well as claim Belgium is an "unnatural" and "artificial" state,[66] formed simply as a buffer between France and other European powers during 19th century conflicts), some public opinion polls performed during the communautary crisis showed that approximately 46% of Flemish people support secession from Belgium.

[70] The resolution had been introduced on October 29 by Bart Laeremans, Gerolf Annemans, Filip De Man and Linda Vissers (Vlaams Belang) and called upon the federal government to "take without delay the measures necessary for the purpose of preparing the break-up of the Belgian State, so the three communities—Flemings, Walloons and Germans—can go their own separate ways.

However La Dernière Heure, L'Avenir and Flemish columnists in De Morgen, Het Laatste Nieuws, and De Standaard condensed Di Rupo's Plan B down to a tactical move in order to put the pressure on the negotiations and redefine the relations between PS and MR.[88] The Plan B proposed by Di Rupo was developed by Christian Berhendt, a specialist of constitutional law at the University of Liège.

According to Berhendt several scenarios are therefore impossible: a unilateral secession of Flanders would be rejected by countries fearing secession of their own minorities, such as China, Russia or Spain, because this would create a precedent they cannot allow; the creation of an autonomous European district in Brussels is not a realistic perspective because the European Union, as it is now, is not able to administer such a large city; a scenario where Flanders and Brussels would form a union is unlikely either because, according to Berhendt, the French-speakers will never agree on such a treaty.