Partitive

Partitives should not be confused with quantitives (also known as pseudopartitives), which often look similar in form, but behave differently syntactically and have a distinct meaning.

In many Romance and Germanic languages, nominal partitives usually take the form: [DP Det.

+ NP]][1]where the first determiner is a quantifier word, using a prepositional element to link it to the larger set or whole from which that quantity is partitioned.

[4] However, this approach fails to account for phrases such as "half of a cookie," that are partitives and yet lack a definite determiner.

It should also be noted that some linguists consider the partitive constraint to be problematic, since there may be cases where the determiner is not always obligatory.

A true partitive, as shown in 5a), has the interpretation of a quantity being a part or subset of an entity or set.

Quantitives, simply denote either a quantity of something or the number of members in a set, and contain a few important differences in relation to true partitives.

[6] Although the syntactic distribution of partitives and pseudo-partitives seems to be complementary, cross-linguistic data suggests this is not always true.

Non-partitives can display an identical syntactic structure as true partitives and the ultimate difference is a semantic one.

Vos pointed out that Dutch contains nominals fulfilling the syntactic criterion but lacking a partitive interpretation; they are therefore classified as non-partitives.

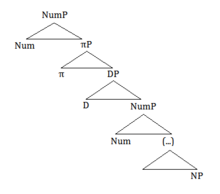

In 1995, Guillermo Lorenzo proposed a partitive (π), which is equivalent to the meaning of "out of" in English, is a functional category by itself and projects to a phrasal level.

The second example has an overt noun inserted between the quantifier and the partitive PP and is still considered grammatical, albeit odd and redundant to a native speaker of Catalan.

Altogether this is taken as strong evidence that an empty noun category should be posited to license a partitive meaning.

The noun following the partitive PP automatically becomes the bigger set and the whole nominal represents a subset-set relation.

Vos claims that it is the relationship between the quantifier and the noun collectively determine the partitive meaning.

[9] Under this view, the preposition belongs to a functional category and its existence is solely for grammatical reasons.

Similarly, de Hoop embraces the idea that only when a quantifier pairs with a desired type of DP, specific kind of partitive relation can then be determined.

The deciding factor to label a partitive construction concerns with the presence of an internal DP, as demonstrated in the English examples below: The nouns in the partitives all refer to a particular bigger set since they are preceded by an internal definite determiner (possessive: my, demonstrative: this and those, and definite article: the).

Intuitively, the last two phrases under the pseudo-partitive column do indicate some kind of partition.

However, when they are broken down into syntactic constituents, noted in true partitives, the noun always projects to a DP.

He proposes that the two constructions have the same logical form, for example 13a), where the word friend has the same referent in both positions.

The NP-related (quantity) condition is if the object is quantitatively indeterminate, which means indefinite bare plurals or mass nouns.

[11] These three conditions are generally considered to be hierarchically ranked according to their strength such that negation > aspect > quantity.

[11] An example of the NP-related condition is shown below, borrowed from Huumo: Löys-i-nfind-PST-1SGvoi-ta.butter-PTVLöys-i-n voi-ta.find-PST-1SG butter-PTV"I found some butter.

The common factor between aspectual and NP-related functions of the partitive case is the process of marking a verb phrase's (VP) unboundness.

Note that when translating Finnish into English, the determiners could surface as "a", "the", "some" or numerals in both unbound and bound events.