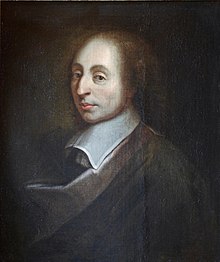

Pascal's wager

[2] The original articulation of this wager can be found in Pascal's posthumously published work titled Pensées ("Thoughts"), which comprises a compilation of previously unpublished notes.

[3] Notably, Pascal's wager is significant as it marks the initial formal application of decision theory, existentialism, pragmatism, and voluntarism.

The argument from inconsistent revelations highlights the presence of various belief systems, each claiming exclusive access to divine truths.

Additionally, the argument from inauthentic belief raises concerns about the genuineness of faith in God if solely motivated by potential benefits and losses.

The wager uses the following logic (excerpts from Pensées, part III, §233): Pascal asks the reader to analyze humankind's position, where our actions can be enormously consequential, but our understanding of those consequences is flawed.

Pascal cites a number of distinct areas of uncertainty in human life: We understand nothing of the works of God unless we take it as a principle that He wishes to blind some and to enlighten others.

The Pensées passage on Pascal's wager is as follows: If there is a God, He is infinitely incomprehensible, since, having neither parts nor limits, He has no affinity to us.

[11]Pascal begins by painting a situation where both the existence and non-existence of God are impossible to prove by human reason.

Pascal's assumption is that, when it comes to making the decision, no one can refuse to participate; withholding assent is impossible because we are already "embarked", effectively living out the choice.

Pascal considers that if there is "equal risk of loss and gain" (i.e. a coin toss), then human reason is powerless to address the question of whether God exists.

The unbeliever who had provoked this long analysis to counter his previous objection ("Maybe I bet too much") is still not ready to join the apologist on the side of faith.

Non-believers questioned the "benefits" of a deity whose "realm" is beyond reason and the religiously orthodox, who primarily took issue with the wager's deistic and agnostic language.

[16][17] The probabilist mathematician Pierre Simon de Laplace ridiculed the use of probability in theology, believing that even following Pascal's reasoning, it is not worth making a bet, for the hope of profit – equal to the product of the value of the testimonies (infinitely small) and the value of the happiness they promise (which is significant but finite) – must necessarily be infinitely small.

[19] Pascal, however, did not advance the wager as a proof of God's existence but rather as a necessary pragmatic decision which is "impossible to avoid" for any living person.

[20] He argued that abstaining from making a wager is not an option and that "reason is incapable of divining the truth"; thus, a decision of whether to believe in the existence of God must be made by "considering the consequences of each possibility".

Voltaire's critique concerns not the nature of the Pascalian wager as proof of God's existence, but the contention that the very belief Pascal tried to promote is not convincing.

Voltaire hints at the fact that Pascal, as a Jansenist, believed that only a small, and already predestined, portion of humanity would eventually be saved by God.

This, its proponents argue, would lead to a high probability of believing in "the wrong god" and would eliminate the mathematical advantage Pascal claimed with his wager.

In "a matter where they themselves, their eternity, their all are concerned",[27] they can manage no better than "a superficial reflection" ("une reflexion légère") and, thinking they have scored a point by asking a leading question, they go off to amuse themselves.

Nevertheless, Pascal concludes that the religion founded by Mohammed can on several counts be shown to be devoid of divine authority, and that therefore, as a path to the knowledge of God, it is as much a dead end as paganism.

"[36] Some critics argue that Pascal's wager, for those who cannot believe, suggests feigning belief to gain eternal reward.

Richard Dawkins argues that this would be dishonest and immoral and that, in addition to this, it is absurd to think that God, being just and omniscient, would not see through this deceptive strategy on the part of the "believer", thus nullifying the benefits of the wager.

[17] William James in his 'Will to Believe' states that "We feel that a faith in masses and holy water adopted wilfully after such a mechanical calculation would lack the inner soul of faith's reality; and if we were ourselves in the place of the Deity, we should probably take particular pleasure in cutting off believers of this pattern from their infinite reward.

What such critics are objecting to is Pascal's subsequent advice to an unbeliever who, having concluded that the only rational way to wager is in favor of God's existence, points out, reasonably enough, that this by no means makes them a believer.

Pascal and his sister, a nun, were among the leaders of Roman Catholicism's Jansenist school of thought whose doctrine of salvation was close to Protestantism in emphasizing faith over works.

[41]Since Pascal's position was that "saving" belief in God required more than logical assent, accepting the wager could only be a first step.

have objected to Pascal's wager on the grounds that he wrongly assumes what type of epistemic character God would likely value in his rational creatures if he existed.

[59] Magnate Warren Buffett has written that climate change "bears a similarity to Pascal's Wager on the Existence of God.

Pascal, it may be recalled, argued that if there were only a tiny probability that God truly existed, it made sense to behave as if He did because the rewards could be infinite whereas the lack of belief risked eternal misery.

Likewise, if there is only a 1% chance the planet is heading toward a truly major disaster and delay means passing a point of no return, inaction now is foolhardy.