Passive cooling

Passive cooling is an important tool for design of buildings for climate change adaptation – reducing dependency on energy-intensive air conditioning in warming environments.

The building structure's thermal mass acts as a sink through the day and absorbs heat gains from occupants, equipment, solar radiation, and conduction through walls, roofs, and ceilings.

[18] For optimal performance, the nighttime outdoor air temperature should fall well below the daytime comfort zone limit of 22 °C (72 °F), and should have low absolute or specific humidity.

[19] For the night flushing strategy to be effective at reducing indoor temperature and energy usage, the thermal mass must be sized sufficiently and distributed over a wide enough surface area to absorb the space's daily heat gains.

There are numerous benefits to using night flushing as a cooling strategy for buildings, including improved comfort and a shift in peak energy load.

By implementing night flushing, the usage of mechanical ventilation is reduced during the day, leading to energy and money savings.

There are also a number of limitations to using night flushing, such as usability, security, reduced indoor air quality, humidity, and poor room acoustics.

For natural night flushing, the process of manually opening and closing windows every day can be tiresome, especially in the presence of insect screens.

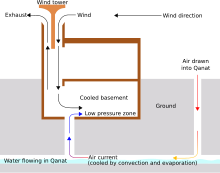

This design relies on the evaporative process of water to cool the incoming air while simultaneously increasing the relative humidity.

[32] An innovative passive system uses evaporating water to cool the roof so that a major portion of solar heat does not come inside.

Earth coupling uses the moderate and consistent temperature of the soil to act as a heat sink to cool a building through conduction.