Pather Panchali

Song of the Little Road) is a 1955 Indian Bengali-language drama film written and directed by Satyajit Ray in his directoral debut and produced by the Government of West Bengal.

Lack of funds led to frequent interruptions in production, which took nearly three years, but the West Bengal government pulled Ray out of debt by buying the film for the equivalent of $60,000, which it turned into a profit of $700,000 by 1980.

Scholars have commented on the film's lyrical quality and realism (influenced by Italian neorealism), its portrayal of the poverty and small delights of daily life, and the use of what the author Darius Cooper has termed the "epiphany of wonder", among other themes.

Together, they share life's simple joys: sitting quietly under a tree, viewing pictures in a travelling vendor's bioscope, running after the candy man who passes through, and watching a jatra (folk theatre) performed by an acting troupe.

[18] The idea appealed to Ray, and around 1946–47, when he considered making a film,[19] he turned to Pather Panchali because of certain qualities that "made it a great book: its humanism, its lyricism, and its ring of truth".

[29] In Apur Panchali (the Bengali translation of My Years with Apu: A Memoir, 1994), Ray wrote that he had omitted many of the novel's characters and that he had rearranged some of its sequences to make the narrative better as cinema.

[30] Changes include Indir's death, which occurs early in the novel at a village shrine in the presence of adults, while in the film Apu and Durga find her corpse in the open.

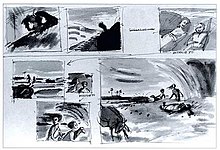

[14] Ray tried to extract a simple theme from the random sequences of significant and trivial episodes of the Pather Panchali novel, while preserving what W. Andrew Robinson describes as the "loitering impression" it creates.

[20] For Robinson, Ray's adaptation focuses mainly on Apu and his family, while Bandopadhyay's original featured greater detail about village life in general.

[43] The Home Publicity Department of the West Bengal government assessed the cost of backing the film and sanctioned a loan, given in instalments, allowing Ray to finish production.

[44] Monroe Wheeler, head of the department of exhibitions and publications at New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA),[45] who was in Calcutta in 1954, heard about the project and met Ray.

Darius Cooper describes the complicated doctrine of rasa as "center[ed] predominantly on feelings experienced not only by the characters but also conveyed in a certain artistic way to the spectator".

[62] He created a piece based on the raga Patdeep, played on the tar shehnai, by Dakshina Mohan Tagore to accompany the scene in which Harihar learns of Durga's death.

It was one of a series of six evening performances at MoMA, including the US debut of sarod player Ali Akbar Khan and the classical dancer Shanta Rao.

Pather Panchali had its domestic premiere at the annual meeting of the Advertising Club of Calcutta; the response there was not positive, and Ray felt "extremely discouraged".

[67] Before its theatrical release in Calcutta, Ray designed large posters, including a neon sign showing Apu and Durga running, which was strategically placed in a busy location in the city.

[74] Despite opposition from some within the governments of West Bengal and India because of its depiction of poverty, Pather Panchali was sent to the 1956 Cannes Film Festival with Nehru's personal approval.

Although some were initially unenthusiastic at the prospect of yet another Indian melodrama, the film critic Arturo Lanocita found "the magic horse of poetry... invading the screen".

[81] Twenty years after the release of Pather Panchali, Akira Kurosawa summarised the effect of the film as overwhelming and lauded its ability "to stir up deep passions".

[44] Bosley Crowther, the most influential critic of The New York Times,[83] wrote in 1958, "any picture as loose in structure or as listless in tempo as this one is would barely pass as a 'rough cut' with the editors in Hollywood", even though he praised its gradually emerging poignancy and poetic quality.

The website's critical consensus reads: "A film that requires and rewards patience in equal measure, Pather Panchali finds director Satyajit Ray delivering a classic with his debut".

[2][a] In 2013, the video distribution company The Criterion Collection, in collaboration with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences' Film Archive, began the restoration of the original negatives of the Apu trilogy, including Pather Panchali.

[97] Author Andrew Robinson, in the book The Apu Trilogy: Satyajit Ray and the Making of an Epic (2010), notes that it is challenging to narrate the plot of Pather Panchali and the "essence of the film lies in the ebb and flow of its human relationships and in its everyday details and cannot be reduced to a tale of events".

[98] In his 1958 New York Times review, Crowther writes that Pather Panchali delicately illustrates how "poverty does not always nullify love" and how even very poor people can enjoy the little pleasures of their world.

[99] Robinson writes about a peculiar quality of "lyrical happiness" in the film, and states that Pather Panchali is "about unsophisticated people shot through with great sophistication, and without a trace of condescension or inflated sentiment".

[100] Darius Cooper discusses the use of different rasa in the film,[101] observing Apu's repeated "epiphany of wonder",[102][g] brought about not only by what the boy sees around him, but also when he uses his imagination to create another world.

Stephen Teo uses the scene in which Apu and Durga discover railway tracks as an example of the gradual build-up of epiphany and the resulting immersive experience.

[106] In contrast to this idealism, Mitali Pati and Suranjan Ganguly point out how Ray used eye-level shots, natural lighting, long takes and other techniques to achieve realism.

[107] Mainak Biswas has written that Pather Panchali comes very close to the concept of Italian neorealism, as it has several passages with no dramatic development, even though the usual realities of life, such as the changing of seasons or the passing of a day, are concretely filmed.

[50] In 1963 Time noted that thanks to Pather Panchali, Satyajit Ray was one of the "hardy little band of inspired pioneers" of a new cinematic movement that was enjoying a good number of imitators worldwide.