Pavel Milyukov

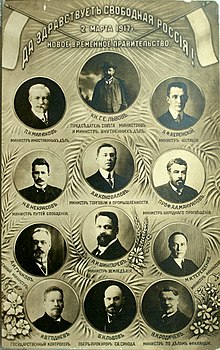

[3] In the Russian Provisional Government, he served as Foreign Minister, working to prevent Russia's exit from the First World War.

Milyukov studied history and philology at the Moscow University, where he was influenced by Herbert Spencer, Auguste Comte, and Karl Marx.

He specialized in the study of Russian history and in 1885 received the degree for work on the State Economics of Russia in the First Quarter of the 18th Century and the reforms of Peter the Great.

[4] When released from jail, Milyukov went to Bulgaria, and was appointed professor in the University of Sofia, where he lectured in Bulgarian [citation needed] in the philosophy of history, etc.

The following by-law, published in 1902 by the governor of Bessarabia, is typical: Forbidden are all gatherings, meetings, and assemblies on streets, market-places, and other public places, whatever aim they may have.

Milyukov drafted the Vyborg Manifesto, calling for political freedom, reforms, and passive resistance to the governmental policy.

Dmitri Trepov suggested Ivan Goremykin ought to step down and promote a cabinet with only Kadets, which in his opinion would soon enter into a violent conflict with the Tsar and fail.

[17] With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Milyukov swung to the right, but a coup to remove the Tsar belonged to the possibilities.

In Summer 1916, at the request of Rodzianko, Protopopov led a delegation of Duma members (with Milyukov) to strengthen the ties with Russia's western allies in World War I: the Entente powers.

He met professor Tomáš Masaryk in London, and consulted with him about the present state of the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia at that time.

Miliukov argued for and secured a tenuous adherence to a middle-ground tactic, attacking Boris Stürmer and forcing his replacement.

According to Stockdale, he had trouble gaining the support of his own party; at the 22–24 October Kadet fall conference provincial delegates "lashed out at Miliukov with unaccustomed ferocity.

He responded with a plea to keep their ultimate goal in mind:[22] It will be our task not to destroy the government, which would only aid anarchy, but to instill in it a completely different content, that is, to build a genuine constitutional order.

The day before the opening of the Duma, the Progressist party pulled out of the bloc because they believed the situation called for more than a mere denunciation of Stürmer.

[23] Alexander Kerensky spoke first, called the ministers "hired assassins" and "cowards" and said they were "guided by the contemptible Grishka [or Grigori] Rasputin!

[26] He highlighted numerous governmental failures, including the case Sukhomlinov, concluding that Stürmer's policies placed in jeopardy the Triple Entente.

Milyukov was taken immediately by Sir George Buchanan to the British Embassy and lived there till the February Revolution;[28] (according to Stockdale he went to the Crimea).

[29] Tsarina Alexandra suggested to her husband to expel Alexander Guchkov, Prince Lvov, Milyukov and Alexei Polivanov to Siberia.

[30] According to Melissa Kirschke Stockdale, it was a "volatile combination of revolutionary passions, escalating apprehension, and the near breakdown of unity in the moderate camp that provided the impetus for the most notorious address in the history of the Duma ...".

Stockdale also points out that Miliukov admitted to some reservations about his evidence in his memoirs, where he observed that his listeners resolutely answered treason "even in those aspects where I myself was not entirely sure.

"[31] Richard Abraham, in his biography of Kerensky, argues that the withdrawal of the Progressists was essentially a vote of no confidence in Miliukov and that he grasped at the idea of accusing Stürmer in an effort to preserve his own influence.

Milyukov wanted the monarchy retained, albeit with Alexei as Tsar and the Grand Duke Michael acting as Regent.

[33] The meeting with Duma President Rodzianko, Prince Lvov, and other ministers, including Milyukov and Kerensky, lasted all morning.

Upon receiving Milykov's request the British freed Trotsky, who then continued his journey to Russia and became a key planner and leader of the Bolshevik Revolution that overthrew the provisional government.

Many of them carried banners with slogans calling for the removal of the "ten bourgeois ministers', for an end to the war and for the appointment of a new revolutionary government.

Milyukov was offered a post as Secretary of Education, but refused; he stayed on as the Kadet leader and began to flirt with counter-revolutionary ideas.

[41]In the mass discontent following the July Days, mainly about Ukrainian autonomy, the Russian populace grew highly skeptical of the Provisional Government's abilities to alleviate the economic distress and social resentment among the lower classes; the word 'provisional' did not command respect.

[43] Because the Petrograd Soviet was able to quickly gather a powerful army of workers and soldiers in defense of the Revolution, Kornilov's coup was an abysmal failure and he was placed under arrest.

Milyukov went to Turkey and from there to Western Europe, to get support from the allies of the White movement, involved in the Russian Civil War.

In April 1921 he immigrated to France, where he remained active in politics and edited the Russian-language newspaper Poslednie novosti (Latest News) (1920–1940).