Peacock Throne

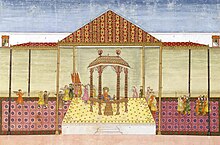

It was commissioned in the early 17th century by Emperor Shah Jahan and was located in the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audiences, or Ministers' Room) in the Red Fort of Delhi.

Shah Jahan ruled in what is now considered the Golden Age of the vast Mughal Empire, which covered almost all of the Indian subcontinent.

Large amounts of solid gold, precious stones, and pearls were used, creating a masterful piece of Mughal artistry that was unsurpassed before or after its creation.

[2] The Peacock Throne was inaugurated in a triumphant ceremony on 22 March 1635, the formal seventh anniversary of Shah Jahan's accession.

[5] The date was chosen by astrologers and was doubly auspicious, since it coincided exactly with Eid al-Fitr, the end of Ramadan, and Nowruz, the Persian New Year.

[6][7] Muhammad Qudsi, the emperor's favourite poet, was chosen to compose twenty verses inscribed in emerald and green enamel on the throne.

He praised the matchless skill of the artisans, the "heaven-depleting grandeur" of its gold and jewels, and included the date in the letters of the phrase "the throne of the just king".

[9] Towards India he turned his reins quickly and went in all glory, Driving like the blowing wind, dapple-grey steed swift as lightning.

[citation needed] When Nadir Shah was assassinated by his officers on 19 June 1747, the throne disappeared, most probably being dismantled or destroyed for its valuables, in the ensuing chaos.

This throne, however, was also lost, possibly during or after the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the subsequent looting and partial destruction of the Red Fort by the British.

[20][21] In 1908, the New York Times reported that Caspar Purdon Clarke, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, obtained what was purported to be a marble leg from the pedestal of the throne.

Inspired by the legend of the throne, King Ludwig II of Bavaria installed a romanticised version of it in his Moorish Kiosk in Linderhof Palace, constructed in the 1860s.

[citation needed] The contemporary descriptions that are known today of Shah Jahan's throne are from the Mughal historians Abdul Hamid Lahori and Inayat Khan, and the French travellers François Bernier and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier.

Abdul Hamid Lahori (d. 1654) describes, in his Padshahnama, the construction of the throne:[25] In the course of years many valuable gems had come into the Imperial jewel-house, each one of which might serve as an ear-drop for Venus, or would adorn the girdle of the Sun.

Upon the accession of the Emperor, it occurred to his mind that, in the opinion of far-seeing men, the acquisition of such rare jewels and the keeping of such wonderful brilliants can only render one service, that of adorning the throne of empire.

It was accordingly ordered that, in addition to the jewels in the Imperial jewel-house, rubies, garnets, diamonds, rich pearls and emeralds, to the value of 200 lacs of rupees, should be brought for the inspection of the Emperor, and that they, with some exquisite jewels of great weight, exceeding 50,000 miskals, and worth eighty-six lacs of rupees, having been carefully selected, should be handed over to Bebadal Khan, the superintendent of the goldsmith's department.

The outside of the canopy was to be of enamel work with occasional gems, the inside was to be thickly set with rubies, garnets, and other jewels, and it was to be supported by twelve emerald columns.

Of the eleven jeweled recesses (takhta) formed around it for cushions, the middle one, intended for the seat of the Emperor, cost ten lakhs of rupees.

By command of the Emperor, the following masnawi, by Haji Muhammad Jan, the final verse of which contains the date, was placed upon the inside of the canopy in letters of green enamel.

It was completed in seven years, and among the precious stones was a ruby worth a lakh of rupees that Shah 'Abbas Safavi had sent to the late Emperor, on which were inscribed the names of the great Timur Sahih-Kiran, etc.

The turban, of gold cloth, had an aigrette whose base was composed of diamonds of an extraordinary size and value, besides an Oriental topaz, which may be pronounced unparalleled, exhibiting a lustre like the sun.

A necklace of immense pearls, suspended from his neck, reached to the stomach, in the same manner as many of the Gentiles wear their strings of beads.

It was constructed by Shah Jahan, the father of Aurangzeb, for the purpose of displaying the immense quantity of precious stones accumulated successively in the treasury from the spoils of ancient Rajas and Patans, and the annual presents to the Monarch, which every Omrah is bound to make on certain festivals.

At the foot of the throne were assembled all the Omralis, in splendid apparel, upon a platform surrounded by a silver railing, and covered by a spacious canopy of brocade with deep fringes of gold.

He was also allowed to inspect the valuable jewels and stones belonging to the emperor but could not see those still kept by Aurangzeb's father, Shah Jahan, who was imprisoned at Agra Fort.

The account of the throne appears in Chapter VIII of Volume II, in which he describes the preparations for the emperor's annual birthday festival and the court's magnificence.

The descriptions of Lahori, from before 1648, and Tavernier's, published in 1676, are generally in broad agreement on the essential features of the thrones, such as its rectangular shape, standing on four legs at its corners, the 12 columns on which the canopy rests, and the type of gemstones embedded on the throne, such as balas rubies, emeralds, pearls, diamonds, and other coloured stones.