Pequot War

[1] Hundreds of prisoners were sold into slavery to colonists in Bermuda or the West Indies;[2] other survivors were dispersed as captives to the victorious tribes.

The result was the elimination of the Pequot tribe as a viable polity in southern New England, and the colonial authorities classified them as extinct.

A series of epidemics over the course of the previous three decades had severely reduced the Indian populations,[5] and there was a power vacuum in the area as a result.

The Dutch and the English from Western Europe were also striving to extend the reach of their trade into the North American interior to achieve dominance in the lush, fertile region.

English Puritans from the Massachusetts Bay, along with the Pilgrims from Plymouth Colony, settled at the recently established river towns of Windsor (1632), Wethersfield (1633), Hartford (1635), and Springfield (1636).

[6] Beginning in the early 1630s, a series of contributing factors increased the tensions between English colonists and the tribes of southeastern New England.

Efforts to control fur trade access resulted in a series of escalating incidents and attacks that increased tensions on both sides.

[9] The initial reactions in Boston varied from indifference to outright joy at Stone's death,[10] but the colonial officials still felt compelled to protest the killing.

[14] A more proximate cause of the war was the killing of a trader named John Oldham, who was attacked on a voyage to Block Island on July 20, 1636.

Several of his crew and he were killed and his ship was looted by Narragansett-allied Indians, who sought to discourage settlers from trading with their Pequot rivals.

Endecott's party of roughly 90 men sailed to Block Island and attacked two apparently abandoned Niantic villages.

Endecott sailed along the coast to a Pequot village, where he repeated the previous year's demand for those responsible for the death of Stone, and now also for those who murdered Oldham.

In May, leaders of Connecticut River towns met in Hartford, raised a militia, and placed Captain John Mason in command.

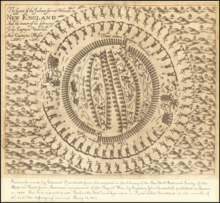

After gaining the support of 200 Narragansetts, Mason and Underhill marched their forces with Uncas and Wequash Cooke about 20 miles towards Mistick Fort (present-day Mystic).

Only 20 soldiers breached the palisade's gate and they were quickly overwhelmed, to the point that they used fire to create chaos and facilitate their escape.

The ensuing conflagration trapped the majority of the Pequots; those who managed to escape the fire were slain by the soldiers and warriors who surrounded the fort.

[23] The Narragansetts and Mohegans with Mason and Underhill's colonial militia were horrified by the actions and "manner of the Englishmen's fight… because it is too furious, and slays too many men.

"[24][25] The Narragansetts attempted to leave and return home, but were cut off by the Pequots from the other village of Weinshauks and had to be rescued by Underhill's men—after which they reluctantly rejoined the colonists for protection and were used to carry the wounded, thereby freeing up more soldiers to fend off the numerous attacks along the withdrawal route.

Sassacus led roughly 400 warriors along the coast; when they crossed the Connecticut River, the Pequots killed three men whom they encountered near Fort Saybrook.

The English surrounded the swamp and allowed several hundred to surrender, mostly women and children, but Sassacus slipped out before dawn with perhaps 80 warriors, and continued west.

According to historian Andrew Lipman, the Pequot War introduced the practice of colonists and Indians taking body parts as trophies of battle.

In 2004, an artist and archaeologist (Jack Dempsey and David R. Wagner) teamed up to evaluate the sequence of events in the Pequot War.

However, Cave contends that Mason and Underhill's eyewitness accounts, as well as the contemporaneous histories of Mather and Hubbard, were more "polemical than substantive.