Percy Glading

On his release from prison near the end of World War II, he is reported to have found work in a factory and maintained close links with Pollitt and the CPGB.

[10] When it was founded, there had been a proposal that a triumvirate composed of Willie Gallacher, David Proudfoot, and Percy Glading act as CPGB leadership; in the event, a single general secretary was appointed.

Robinson says Glading saw their trial as violating the men's "fundamental civil liberties"[40]—particularly as the group had to wait over two years to even be brought to trial—and that this made them "the final justification for the eventual overthrow of the ruling class" in India.

[40] Glading had been arrested along with M. N. Roy (who has been described by William E. Duff as a "paid Comintern agitator") and fifty-six other men, but, there being insufficient evidence to hold him, was released.

[41] Glading's original purpose in India, on behalf of the CPGB, was seeking to forge links with Roy as well as to study Indian working conditions specifically and more generally to promote the Communist Party.

[42] Indian Political Intelligence noted that Glading had particularly focussed his attention on "shipyards, munitions works, dockyards and arsenals where strike committees or 'Red Cells' existed".

Efforts included discussions with Labour MPs in parliament and barraging Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin with demands that he personally overturn the sacking.

[34][note 13] Glading's obituary, written later by Rajani Dutt, made no mention of the Lenin School, reporting that he spent "a year in the Soviet Union where he witnessed the great agrarian changeover from individual petty-bourgeoise holdings to collective farming".

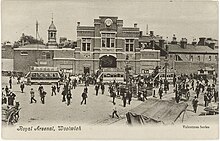

[71] In the post-World War One period, an upsurge in communist activity in British industry, particularly in armaments and munitions factories led to employers in these sectors beginning to lay off workers suspected of left-wing sympathies.

[81] Historian David Burke says it seems likely that the Woolwich spy ring was created by the NKVD to gain possession of a top-secret large naval gun that the Arsenal was believed to be researching.

[note 19] Much of Glading's operation at this time would have been concerned with the on-going deadlock at the Montreux Convention, at which Britain, France, Italy and the Soviet Union disputed their proposed access to the Black Sea with Turkey.

[92] Maly and Deutsch requested the assistance of James Klugmann[note 20]—then living in Paris—later an important asset for Soviet Intelligence within the Special Operations Executive (SOE)[88] who was acquainted with Cairncross.

This was Mikhail Borovoy, a member of the OGPU's Technical Section, who was travelling with his wife under false Canadian passports (as Willy and Mary Brandes) and had arrived in London in October 1936.

[102] It was immediately after Glading met the Brandes that he instructed Olga Gray to find a suitable flat or apartment (for example, he specified that there should be no porter to espy their comrades' comings and goings).

[97][note 23] Glading's operation at Woolwich consisted of George Whomack smuggling out blueprints at the end of a late shift—past military police guards—on the day the document had been released to the arsenal.

[104] Should MI5 have discovered the name of a person described by Olga Gray...as 'another man short and rather bumptious in manner' who was working with Glading, they would have had no problem in finding out everything else about Dr Deutsch.

The team focussed on photography[110]—which Glading told her was of "a very secret nature"[109]—and began extensive testing (on local bus maps) with home-made cameras to make the end product as clear to their Russian recipients as possible.

[112] Deutsch had run the Soviet spy network in England since February 1934, and Glading began introducing other people to him for recruitment (in one case, a father, swiftly followed by his son).

MI5 knew of his interest in the fourteen-inch heavy naval gun that was now in production at the Royal Arsenal, and that Whomack was removing the blueprints for it and bringing them to Holland Road for copying.

Although the men could be searched by the Arsenal's security on entry, even the simple expedient of folding the plans between a folded-up newspaper was sufficient to avoid detection on at least one occasion.

[126] Imprisoned before trial, it is possible that he confessed his leading role in the organisation to a fellow inmate, although doubt has been cast on whether the Woolwich spy ring was ever big enough to warrant a strict hierarchy of its own.

Hennessey and Thomas have argued that, at this point, "the reality of her role struck home: that she had effectively destroyed a man who had trusted her implicitly and of whom she had become extremely fond".

[131] Ironically, in case anyone was in any doubt as to the importance placed upon the naval gun, the Attorney General, questioned by the Judge, emphasised its significance in open court.

Duff argues it is possible that this was the result of his making a deal with MI5 to turn king's evidence and reveal the tradecraft of Glading's operation at the Royal Arsenal.

[136] It had the negative consequence (for the service), however, of reinforcing the erroneous notion that the CPGB was the most dangerous security threat of the period,[149] and that members of the party were all willing tools of the NKVD.

[158] Lord Robert Cecil compared it to "an imaginary soccer match between Manchester United and Corinthian Casuals",[159] such was the disparity between the Soviet and British security services in resources, professionalism and influence.

Guy Liddell, a colleague of Sissimore's in the secret service, later wrote in his diary entry for 13 October 1939: When interviewed Glading was rather stuffy at first but gradually, under a great deal of flattery, his own conceit got the better of him.

[137] By the time Glading was released, Pollitt had lost his post as General Secretary to the CPGB in a split within the Central Committee, in 1939, over Stalin's rapprochement with Hitler.

P. E. Glading", he was presented with a ceremonial copy of James George Frazer's seminal work, The Golden Bough, by the North London District Committee of the Amalgamated Engineering Union.

The official White Paper containing the documents found in the raid was thin evidence indeed, and led to no arrests or charges for illegal or subversive activities by Russian or British subjects.