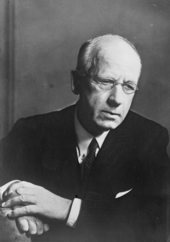

Peter Fraser

Fraser is best known for leading the country during the Second World War when he mobilised New Zealand supplies and volunteers to support Britain while boosting the economy and maintaining home front morale.

A native of Scotland, Peter Fraser was born in Hill of Fearn, a small village near the town of Tain in the Highland area of Easter Ross.

Though apprenticed to a carpenter, he eventually abandoned this trade due to extremely poor eyesight – later in life, faced with difficulty reading official documents, he would insist on spoken reports rather than written ones.

[2] In another two years, at the age of 26, after unsuccessfully seeking employment in London, Fraser decided to move to New Zealand, having apparently chosen the country in the belief that it possessed a strong progressive spirit.

He gained employment as a stevedore (or "wharfie") on arrival in Auckland, and became involved in union politics upon joining the New Zealand Socialist Party.

While the arrest led to no serious repercussions, it did prompt a change of strategy – he moved away from direct action and began to promote a parliamentary route to power.

[5] Fraser polled higher than any Labour mayoral candidate in New Zealand history but lost by only 273 votes to Robert Wright in the closest result Wellington had ever seen.

Although initially enthusiastic about the Russian October Revolution of 1917 and its Bolshevik leaders, he rejected them soon afterwards, and eventually became one of the strongest advocates of excluding communists from the Labour Party.

Fraser's views clashed considerably with those of Harry Holland, still serving as leader, but the party gradually shifted its policies away from the more extreme left of the spectrum.

With Labour now possessing a "softer" image and the existing conservative coalition struggling with the effects of the Great Depression, Savage's party succeeded in winning the 1935 election and forming a government.

[1] Fraser's narrowly elitist and Anglophile cultural perspectives are illustrated by his crucial role in planning New Zealand's 1940 Centennial celebrations.

The Act proposed a comprehensive health care system, free at the point of use; it faced strong opposition, particularly from the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association.

He believed that the more populous countries, particularly Britain, viewed New Zealand's military as a mere extension of their own, rather than as the armed forces of a sovereign nation.

When Japan entered the war in December 1941, Fraser had to choose between recalling New Zealand's forces to the Pacific (as Australia had done) or keeping them in the Middle East (as British prime minister Winston Churchill requested).

Fraser weighed up public opinions against the strategic arguments involved and eventually opted to leave New Zealand's Expeditionary Force where it was.

[1] In a remarkable display of political acumen and skill, he then persuaded a divided government and Parliament to give their full support [to leave the army in Africa].

By early 1943 Fraser faced a major military and strategic problem that also had significant political implications in this New Zealand election year.

Moreover, unions had ensured that bonuses and high pay were awarded to munitions workers, far in excess of the money paid to the men in combat.

Due to censorship, the public heard little of the protests and the affair, known as the "Furlough Mutiny", was omitted from post-war history books for many years.

[1] New Zealand and Australia were both anxious to have their input in the planning of the Pacific War, and later in the decisions of the "Great Powers" in the shaping of the post-war world.

[23] Noteworthy for his strong opposition to vesting powers of veto in permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, he often spoke unofficially for smaller states.

The Maori Social and Economic Advancement Act, which he introduced in 1945, allowed Māori involvement and control over welfare programmes and other assistance.

Ironically, the National opposition prompted the adoption of the Statute in 1947 when its leader and future prime minister Sidney Holland introduced a private members' bill to abolish the Legislative Council, the country's upper house of parliament.

Fraser knew his domestic audience and was tough on republicanism or defence weakness to deflect criticism from the loyalist and imperialist-minded opposition National Party.

Labour had been in office for fourteen years and faced an uphill battle to retain power against National at the general election, which would come just months after the high-profile April 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference.

In March 1949 Fraser wrote to the Canadian prime minister, Louis St Laurent, stating his frustration and unease over India's position.

From 1940 to 1949 Fraser lived in a house "Hill Haven" at 64–66 Harbour View Road, Northland, Wellington, which had been purchased for the use of the then-ill Savage in 1939.

As a result, the gap between the party leadership and rank and file members widened to the point where Labour's political enthusiasm dwindled.

[32] On 1 November 1919, a year after his election to parliament, Fraser married Janet Kemp née Munro, from Glasgow and also a political activist.

[33] During Fraser's time as prime minister, Janet traveled with him and acted as a "political adviser, researcher, gatekeeper and personal support system".