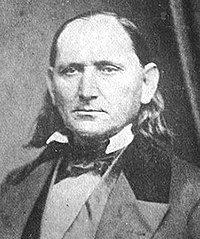

Peter Pitchlynn

A long-time diplomat between his tribe and the federal government, he served as principal chief of the Choctaw Republic from 1864 to 1866 and surrendered to the Union on behalf of the nation at the end of the Civil War.

After joining his people on the forced removal to Indian Territory in the 1830s, he was appointed by the National Council in 1845 as the Choctaw Delegate (akin to an ambassadorship) to Washington.

Peter Perkins Pitchlynn was born on January 30, 1806, in present-day Noxubee County, Mississippi, which at the time, was part of the Old Choctaw Nation.

[4] As the Choctaw had a matrilineal kinship system of property and hereditary leadership, Peter was born into his mother's clan and people; through her family, he gained status in the tribe.

One of ten children born to the Pitchlynns, after several years at home, Peter was sent to a Tennessee boarding school about 200 miles from Mississippi.

[6] In 1824, Pitchlynn was made the head of the Lighthorse, the Choctaw Nation's mounted police, and received the rank of colonel.

[9] The Pitchlynn sons had difficulties as youths and adults: Lycurgus and Leonidas were convicted of assault in 1857 and sentenced to prison.

[9] In 1860, Peter Jr. shot and killed his uncle, Lorenzo Harris, who was married to his father's sister Elizabeth Pitchlynn.

Believing that education was important, he persuaded the National Council to found the Choctaw Academy, located in Blue Springs, Scott County, Kentucky in 1825.

[4] While Pitchlynn originally inherited slaves from his father, unlike other Choctaw slaveholders like Robert M. Jones, he felt an indifference towards the institution.

[12] English author Charles Dickens was touring the United States when he met Pitchlynn on a steamboat on the Ohio River.

He described the Choctaw leader at length: He was a remarkably handsome man; some years past forty, I should judge; with long black hair, an aquiline nose, broad cheek-bones, a sunburnt complexion, and a very bright, keen, dark, and piercing eye.

When we shook hands at parting, I told him he must come to England, as he longed to see the land so much: that I should hope to see him there, one day: and that I could promise him he would be well received and kindly treated.

He was evidently pleased by this assurance, though he rejoined with a good-humoured smile and an arch shake of his head, that the English used to be very fond of the Red Men when they wanted their help, but had not cared much for them, since.

That year both the Choctaw and Cherokee proposed to the US Congress that their respective nations should be recognized as independent United States territories, but this was not supported.

[19] The Choctaws laid down their arms, and the Union took control of the territory until a formal peace treaty was signed the following spring.

He had been collecting information on this issue since the 1850s from officials involved in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek,[9] and later joined the Lutheran Church.

He resisted the incorporation of the freedmen, arguing the Treaty of 1866 made them American citizens after the Choctaw did not adopt them, and thus they were not entitled to rights within the tribe.

Even when they first made their appearance upon the earth they were so numerous as to cover the sloping and sandy shore of the ocean ... in the process of time, however, the multitude was visited by sickness ... their journey lay across streams, over hills and mountains, through tangled forests, and over immense prairies ... so pleased were they with all that they saw that they built mounds in all the more beautiful valleys they passed through, so the Master of Life might know that they were not an ungrateful people.