Peterloo Massacre

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, there was an acute economic slump, accompanied by chronic unemployment and harvest failure due to the Year Without a Summer, and worsened by the Corn Laws, which kept the price of bread high.

Radicals identified parliamentary reform as the solution, and a mass campaign to petition parliament for manhood suffrage gained three-quarters of a million signatures in 1817 but was flatly rejected by the House of Commons.

The event was first labelled the "Peterloo massacre" by the radical Manchester Observer newspaper in a bitterly ironic reference to the bloody Battle of Waterloo which had taken place four years earlier.

[2] The London and national papers shared the horror felt in the Manchester region, but Peterloo's immediate effect was to cause the Tory government under Lord Liverpool to pass the Six Acts, which were aimed at suppressing any meetings for the purpose of radical reform.

In 2019, on the 200th anniversary of the massacre, Manchester City Council inaugurated a new Peterloo Memorial by the artist Jeremy Deller, featuring eleven concentric circles of local stone engraved with the names of the dead and the places from which the victims came.

[4] Nationally, the so-called rotten boroughs had a hugely disproportionate influence on the membership of the Parliament of the United Kingdom compared to the size of their populations: Old Sarum in Wiltshire, with one voter, elected two MPs,[5] as did Dunwich in Suffolk, which by the early 19th century had almost completely disappeared into the sea.

The cost of food rose as people were forced to buy the more expensive and lower quality British grain, and periods of famine and chronic unemployment ensued, increasing the desire for political reform both in Lancashire and in the country at large.

In September 1818 three former leading Blanketeers were again arrested for allegedly urging striking weavers in Stockport to demand their political rights, 'sword in hand', and were convicted of sedition and conspiracy at Chester Assizes in April 1819.

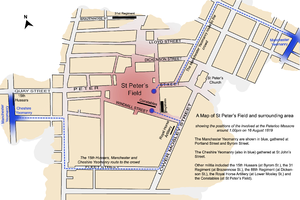

[9] In January 1819, a crowd of about 10,000 gathered at St Peter's Fields to hear the radical orator Henry Hunt and called on the Prince Regent to choose ministers who would repeal the Corn Laws.

In July 1819, the magistrates wrote to Lord Sidmouth warning they thought a "general rising" was imminent, the "deep distress of the manufacturing classes" was being worked on by the "unbounded liberty of the press" and "the harangues of a few desperate demagogues" at weekly meetings.

Johnson wrote: Nothing but ruin and starvation stare one in the face [in the streets of Manchester and the surrounding towns], the state of this district is truly dreadful, and I believe nothing but the greatest exertions can prevent an insurrection.

The magistrates were convinced that the situation was indeed an emergency which would justify pre-emptive action, as the Home Office had previously explained, and set about lining up dozens of local loyalist gentlemen to swear the necessary oaths that they believed the town to be in danger.

[36] Recently mocked by the Manchester Observer as "generally speaking, the fawning dependents of the great, with a few fools and a greater proportion of coxcombs, who imagine they acquire considerable importance by wearing regimentals,"[37] they were subsequently variously described as "younger members of the Tory party in arms",[8] and as "hot-headed young men, who had volunteered into that service from their intense hatred of Radicalism.

[32] Samuel Bamford recounts the following incident, which occurred as the Middleton contingent reached the outskirts of Manchester: On the bank of an open field on our left I perceived a gentleman observing us attentively.

[49]Although William Robert Hay, chairman of the Salford Hundred Quarter Sessions, claimed that "The active part of the meeting may be said to have come in wholly from the country",[50] others such as John Shuttleworth, a local cotton dealer, estimated that most were from Manchester, a view that would subsequently be supported by the casualty lists.

Believing that this might be intended as the route by which the magistrates would later send their representatives to arrest the speakers, some members of the crowd pushed the wagons away from the constables, and pressed around the hustings to form a human barrier.

[57] William Hulton, the chairman of the magistrates watching from the house on the edge of St Peter's Field, saw the enthusiastic reception that Hunt received on his arrival at the assembly, and it encouraged him to action.

[60] Sixty cavalrymen of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, led by Captain Hugh Hornby Birley, a local factory owner, arrived at the house from where the magistrates were watching; some reports allege that they were drunk.

"[69] On the other hand, Lieutenant Jolliffe of the 15th Hussars said "It was then for the first time that I saw the Manchester troop of Yeomanry; they were scattered singly or in small groups over the greater part of the Field, literally hemmed up and powerless either to make an impression or to escape; in fact, they were in the power of those whom they were designed to overawe and it required only a glance to discover their helpless position, and the necessity of our being brought to their rescue" [70] Further Jolliffe asserted that "... nine out of ten of the sabre wounds were caused by the Hussars ... however, the far greater amount of injuries were from the pressure of the routed multitude."

[45] A recently unearthed set of 70 victims' petitions in the parliamentary archives reveals some shocking tales of ferocity, including the accounts of the female reformers Mary Fildes, who carried the flag on the platform, and Elizabeth Gaunt, who suffered a miscarriage following ill-treatment during eleven days' detention without trial.

James Wroe, editor of the Manchester Observer, was the first to describe the incident as the "Peterloo Massacre", coining his headline by creating the ironic portmanteau from St Peter's Field and the Battle of Waterloo that had taken place four years earlier.

Cotton merchants Archibald Prentice (later editor of The Manchester Times) and Absalom Watkin (a later corn-law reformer), both members of the Little Circle, organised a petition of protest against the violence at St Peter's Field and the validity of the magistrates' meeting.

"[93] In an open letter, Richard Carlile said: Unless the Prince calls his ministers to account and relieved his people, he would surely be deposed and make them all REPUBLICANS, despite all adherence to ancient and established institutions.

Encouraging them in that belief were two abortive uprisings, in Huddersfield and Burnley, the Yorkshire West Riding Revolt, during the autumn of 1820, and the discovery and foiling of the Cato Street conspiracy to blow up the cabinet that winter.

"[100] Events such as the Pentrich rising, the March of the Blanketeers and the Spa Fields meeting, all serve to indicate the breadth, diversity and widespread geographical scale of the demand for economic and political reform at the time.

[110] At the centenary in 1919, just two years after the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik coup, trade unionists and communists alike saw Peterloo as a lesson that workers needed to fight back against capitalist violence.

The Conservative majority on Manchester City Council in 1968–1969 declined to mark the 150th anniversary of Peterloo, but their Labour successors in 1972 placed a blue plaque high up on the wall of the Free Trade Hall, now the Radisson Hotel.

[116] Under the heading "St. Peter's Fields: The Peterloo Massacre", the present plaque reads, "On 16th August 1819 a peaceful rally of 60,000 pro-democracy reformers, men, women and children, was attacked by armed cavalry resulting in 15 deaths and over 600 injuries.

[117] It was inaugurated at a large public gathering on 16 August 2019, widely reported in the press, covered extensively on regional TV and radio, and marked by a special edition of the Manchester Evening News.

Sean Cooney, songwriter, folk singer and member of The Young'uns, wrote a work consisting of 15 original songs and a spoken narrative commemorating the Peterloo Massacre.