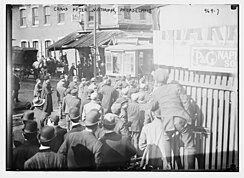

Philadelphia general strike (1910)

[2][3][1] On May 29, 1909, a committee of the local AFL affiliate Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America approached officials of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT) with demands for an hourly wage of 25 cents for motormen and conductors, the right to buy their uniforms on the open market, limits of workdays to 9 or 10 hours and recognition of the Association.

Given the population's general dislike of the company for poor service, mismanagement and backroom political dealings, the union felt safe issuing an ultimatum.

The workers received a wage increase from 21 to 22 cents per hour, a ten-hour work day, the right to buy uniforms from five clothiers and recognition of the union.

PRT flatly refused and on January 1, 1910, without union discussion, announced a complicated "welfare plan" for the workers; keeping the 22 cents an hour pay rate and adding insurance and pension provisions.

Local newspapers, citing the near unanimity of the vote and the union's obvious strength, urged PRT to give the situation urgent attention.

Mayor Reyburn endorsed the company's position, calling the union members "semi-public functionaries" who owe their service to the city.

[2] At Smith's Hall, police commandeered heavy equipment to force their way in while the mob showered them with rocks, bricks and tools from a second-story window.

[2] In stark contrast to the chaos throughout the city, the union leaders enjoyed a sort of victory parade, taxied through cheering crowds to a series of speeches at several locations.

[7] The final straw for calling a general strike was the National Guard and the Pennsylvania Constabulary entering the city to provide protection for PRT's few remaining workers.

[4][7] When the well-trained, heavily armed Constabulary failed to immediately restore order, there was talk of bringing in the United States Army or Navy.

[9] The union's "scorched earth, take no prisoners" approach eventually brought PRT to the negotiating table, ending the general strike while the trolley walk-out continued.

She stated that there would be men in the parade, but only to hold babies and push strollers so that the women marchers would have their hands free to collect donations.

[4] The women's auxiliary went on to raise funds through a variety of sales, entertainment events and door-to-door solicitions, allowing the strikers to continue far longer than they could have afforded to otherwise.

Eventually, the disgruntled riders managed to freeze trolley fares at 5 cents well beyond the fiscal pressures of most traction companies, ironically leading to severely under-funded transit systems and bankrupt rail lines.