Philadelphia transit strike of 1944

[1][3] The strike paralyzed the public transport system in Philadelphia for several days, bringing the city to a standstill and crippling its war production.

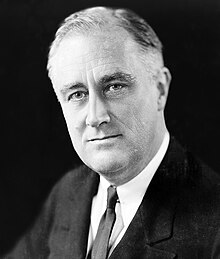

On August 3, 1944, under the provisions of the Smith–Connally Act, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to take control of the Philadelphia Transportation Company, and Major-General Philip Hayes was put in charge of its operations.

[7] However, the PTC's black workers had been restricted to holding menial jobs; none were allowed to serve as conductors or motormen – positions that were reserved for white employees.

[7] The black PTC employees enlisted the help of the NAACP and started lobbying the federal authorities, particularly the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC), to intervene.

In January 1943 the PTC requested 100 white motormen from the United States Employment Service (USES),[8] which was a part of the War Manpower Commission (WMC).

The FEPC made a series of unsuccessful attempts to convince the PTC management and the union leadership to change their stance and to allow promotions of black employees to non-menial jobs.

The PTC eventually conceded that it would be willing to go along with the government's request and "employ Negroes, provided they are acceptable to fellow-workers",[9] but the PRTEU leadership, particularly Frank Carney, staunchly resisted.

On November 17, 1943, the FEPC issued a directive requiring that PTC end its discriminatory employment practices and allow blacks to hold non-menial jobs.

[10] At the hearing the union tried to make the argument that hiring blacks who had applied for the non-menial positions since June 1941 but were denied would adversely affect the seniority rights of the presently employed white workers.

[10] In an attempt to deflect the pressure, Carney and PRTEU contacted Virginia congressman Howard W. Smith, who at the time was the Chair of the House Committee to Investigate Executive Agencies.

[12] The hearing was inconclusive, with Ross reiterating the FEPC position, and the union representatives falling back on the "customs clause" and their claims about seniority issues.

[13] A petition, signed by 1776 workers, presented at the hearing, read: "Gentlemen: We, the white employees of the Philadelphia Transportation Co., refuse to work with Negroes as motormen, conductors, operators and station trainmen".

[13] Following the January 11 congressional hearing, Malcolm Ross’s delay in enforcing the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) directive was not just a waiting game; it highlighted the complex landscape of labor relations and racial tensions within the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC).

This rapid demographic shift heightened anxieties among white Philadelphians, particularly as Black workers pushed for better employment opportunities amidst labor shortages.

With labor shortages growing critical, national attention on racial discrimination in wartime industries intensified, and the FEPC, bolstered by a partnership with the War Manpower Commission, began to push harder against PTC’s discriminatory policies.

The Transport Workers Union (TWU), a CIO affiliate, ran on a platform supporting the promotion of Black employees, contrasting sharply with the PRTEU’s racially exclusionary stance.

The ongoing contract negotiations between TWU and PTC became a prolonged struggle, emblematic of the deep-seated racial and labor tensions that still permeated Philadelphia’s transit system during the war.

In view of growing labor shortages, on July 1, 1944 the War Manpower Commission made an important decision, ruling that from then on all hiring of male employees in the country was to be done through the United States Employment Service (USES).

There were postings on PTC bulletin boards urging non-compliance with the new policy, and a petition was circulated calling for a strike to protest job upgrades of black employees.

[15] On the morning of August 1, PTC officials immediately shut down the high-speed lines, even before the strike had spread, and instructed the company supervisors to stop selling tickets.

[16] The company also cancelled the regularly scheduled meeting of its executive committee, where the response to the strike could have been discussed, and refused to join the TWU in a radio broadcast urging the strikers to return to work.

At 7:45 p.m. on August 3, in his twenty-fifth seizure order under the Smith–Connally Act, President Roosevelt authorized the Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to take control of the Philadelphia Transportation Company.

He posted the President's order on the PTC carbarns and announced that the Army hoped to avoid using the troops and would try to rely on the local and state police to the extent possible.

Hayes and his staff warned the strikers about the severe penalties provided by the Smith–Connally Act for disruption of the war production: the instigators could be subject to a fine of $5,000, one year in prison, or both.

[22] This prospect was made more real when the United States Attorney General Francis Biddle started an inquiry into possible violations of federal laws by the strike organizers.

[29] Samuel also refused to grant air time to War Production Board representatives who wanted to make a radio plea to end the strike.

[34] The conservative-leaning Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune, while denouncing the strike, tried to put the blame for causing it on the CIO-affiliated Transport Workers Union, and accused the Roosevelt administration of acting too slowly because of its support for the CIO.

[2] Another historian, Alan M. Winkler, also had a largely negative view of the company's role in the conflict and concluded that PTC management, while not overtly conspiring with the strikers, reacted feebly to the strike and tried to opportunistically exploit the situation and the racist attitudes of many white workers for their own purposes.

[42] As labor historian James Wolfinger observed, the strike "demonstrated the profound racial cleavages, that divided the working class, not just in the South but across the nation".

[47] Nevertheless, the strike demonstrated that a combination of black activism, particularly by the NAACP, together with resolute federal policies, were able to break long standing racial barriers in employment.