Philip III, Bishop of Fermo

His activity between 1279 and 1281 – mostly regarding the persecution of the Cumans – significantly interfered in Hungarian domestic politics and, contrary to his original mandate and intent, contributed to the deepening of feudal anarchy and the suppression of royal power against the emerging oligarchs.

[2] On 31 March 1278, Pope Nicholas III entrusted Philip and Comes de Casate to carry out visits to monasteries, hospitals, churches and chapels under his direct papal jurisdiction in Rome.

[7] After his return from Eastern Europe to Italy, Philip kept a low profile and devoted the last years of his life to the improvement of the administration of the Diocese of Fermo: for instance, by introducing the office of vicar general and raising church discipline to a higher level.

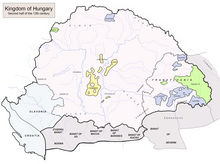

But having effected nothing with the king, he returned home.Pope Nicholas III appointed Philip as papal legate with "full jurisdiction" (legationis officio plene) to Hungary and its adjacent territories, Poland, Dalmatia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Galicia–Volhynia and Cumania ("ac Polonie, Dalmatie, Croatie, Rame, Servie, Lodomirie, Galitie et Cumanie partibus illi conterminis") on 22 September 1278.

[4] Despite Philip was not a member of the College of Cardinals, he was granted the rank legatus a latere,[10] consequently he was the "alter ego" of the pope and thus possessed full plenipotentiary powers.

[10] As a result of his rank legatus a latere, Philip was mandated to donate church benefice; he could appoint his clergy as canons in any chapter; he was authorized to grant indulgence; he could also enforce the imposition of his measures with censure (i.e. excommunication, interdict and suspension), in addition to lifting those punishments.

[11] The pope marked his chief duty in assisting King Ladislaus IV of Hungary to consolidate his authority and restore royal power, in addition to defend the rights and freedoms of ecclesiastical institutions against tyrannical secular lords.

Although, the kingdom fell into feudal anarchy in 1272, when the minor Ladislaus was crowned king, and in the following years baronial groups fought for supreme power which also affected serious damage to ecclesiastical property (for instance, the Diocese of Veszprém was ravaged and devastated in 1276), by the time Philip was appointed, Ladislaus IV had achieved significant results in the field of political consolidation: after he was declared to be of age in May 1277, he successfully eliminated the dominion of the Geregye clan, while forcing the powerful Kőszegi family to retreat temporarily.

Simultaneously, the joint German–Hungarian army decisively defeated the Bohemians and killed the archenemy King Ottokar II of Bohemia at the Battle on the Marchfeld in August 1278.

[15][16] Based on Ottokar aus der Gaal's Steirische Reimchronik ("Styrian Rhyming Chronicle"), historian Viktória Kovács considered the appointment of a papal legate could have been preceded by a request in Hungary.

Bruno von Schauenburg, the Bishop of Olomouc (and King Ottokar's advisor) in 1272 already informed Pope Gregory on the "dangerous situation" of Christianity in Hungary, for which he made the Cumans primarily responsible.

[16] Pope Nicholas III mentioned in a 7 October 1278 letter that Catholics had disappeared from the Diocese of Cumania (or Milkovia) because no bishop lived there since the destruction of the episcopal see during the Mongol invasion of Hungary.

[20] Around the same time, Philip also excused brothers Mikod and Emeric Kökényesradnót from their oath to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, in exchange to finance the reconstruction of the cathedral.

By the time of the arrival of papal legate Philip, two representatives of the rival baronial groups, Nicholas Kán and Peter Kőszegi fought for the position.

Philip was willing to release Nicholas from the excommunication in May 1279, if he resign from the title, return the usurped lands and treasures, and leave Hungary for a pilgrimage to Rome.

On the same day, the pope instructed Philip to investigate the circumstances and regularity of the election of John Hont-Pázmány as the Archbishop of Kalocsa, which took place in the previous year.

[23] In the midst of adoption of the so-called Cuman laws (see below), Philip convened a national synod attending all prelates of the realm – archbishops Lodomer, John Hont-Pázmány and their suffragans – to Buda in September 1279.

Accordingly, he instructed Walter, the judge of Buda and the burghers not to allow the prelates gathering for the synod to enter the castle and not to feed them and their entourage (familiae eorumdem).

[24][25][26] Upon Philip's request, the synod also prescribed restrictive measures against non-Christian subjects: Jews were obliged to wear a red circular patch over their breast on the left side of their outer garment, Muslims a similar sign in yellow.

Following the verdict of his protege Archbishop Lodomer, Philip confirmed the privilege of the monastery of nuns located in the valley of Veszprém to collect local tithe, which was unlawfully usurped by Bishop Peter Kőszegi.

[33] Philip summoned a general assembly (generalis congregatio) to Tétény (today a borough of Budapest) in July 1279, where further laws were set down on 10 August 1279.

[39] Pálóczi Horváth considered the attending Cuman chieftains – Alpra and Uzur – managed to obtain certain compromises, as the second document also contained their privileges beside their obligations.

Szűcs emphasized the bishops were forced to bow their heads before Philip's "authoritarian violence", some of the nobility was defeated by demagoguery, and the rebellion matured among the Cumans.

[44] However, reconciliation between Ladislaus and Philip proved to be only temporary, and the Hungarian monarch left the capital for Semlak in Temes County (Tiszántúl) and settled among the Cumans, finally choosing the latter in his intractable dilemma.

On 9 December 1279, Pope Nicholas III sent a letter to the king, in which he rebuked him for his resistance and for his pagan customs and Cuman concubines (thus Aydua, the most famous of them).

[20] The Steirische Reimchronik incorrectly claims that immediately after his liberation, Philip left Hungary for Italy, and "arriving to Zadar, he swore to God that the king and all of his men could become a pagan from his apart, he would no longer set foot on Hungarian soil".

[47] For the rest of his tenure as papal legate, Philip was no longer actively involved in the political affairs of the kingdom, but the escalation of the Cuman question had long-lasting consequences for the history of Hungary.

Ladislaus gathered an army around October 1280 and chased the outgoing Cumans as far as Szalánkemén (now Stari Slankamen in Serbia) and also crossed the border at the Carpathians.

[50] He arrived to Silesia in the following months: he resided in Wrocław from February to April 1282, but also issued charters in Milicz, Wieluń, Henryków and Lipowa throughout the year.

[52] He unsuccessfully tried to mediate in the violent dispute between Thomas II, bishop of Wrocław and Duke Henry IV the Righteous over the prerogatives of the Church in Silesia.