Philippines campaign (1941–1942)

On 8 December 1941, several hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese planes began bombing U.S. forces in the Philippines, including aircraft at Clark Field near the capital of Manila on the island of Luzon.

Japanese troops captured Manila by 7 January 1942, and after their failure to penetrate the Bataan defensive perimeter in early February, began a 40-day siege, enabled by a naval blockade of the islands.

The campaign to capture the Philippines took much longer than planned by the Japanese, who in early January 1942 had decided to advance their timetable of operations in Borneo and Indonesia and withdraw their best division and the bulk of their airpower.

Five years earlier, in 1936, Captain Ishikawa Shingo, a hard-liner in the Imperial Japanese Navy, had toured the Philippines and other parts of the Southeast Asia, noting that these countries had raw materials Japan needed for its armed forces.

[16]: 21 The Formosa-based 48th Division, although without combat experience, was considered one of the Japanese Army's best units, was specially trained in amphibious operations, and was given the assignment of the main landing in Lingayen Gulf.

[16]: 24 From mid-1941, following increased tension between Japan and several other powers, including the United States, Britain and the Netherlands, many countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific began to prepare for the possibility of war.

Training was also seriously inhibited by language difficulties between the American cadres and the Filipino troops, and by the many differing dialects (estimated at 70) of the numerous ethnic groups comprising the army.

As personnel were routinely transferred back to the United States or separated from the service, the regimental commander, Colonel Samuel L. Howard, arranged unofficially for all replacements to be placed in the 1st Special Defense Battalion, based at Cavite.

[35] An initial plan to divide the 4th into two regiments, mixing each with a battalion of Philippine Constabulary, was discarded after Howard showed reluctance, and the 4th was stationed on Corregidor to augment the defenses there, with details detached to Bataan to protect USAFFE headquarters.

[41] Authorization was withheld, but shortly afterward, in response to a telegram from General George C. Marshall instructing MacArthur to implement Rainbow 5, Brereton was ordered to have a strike in readiness for later approval.

[40][42] The 3rd Pursuit Squadron took off from Iba at 11:45 with instructions to intercept the western force, which was thought to have Manila as its target, but dust problems during its takeoff resulted in the fragmentation of its flights.

After the war, Brereton and Sutherland in effect blamed each other for FEAF being surprised on the ground, and MacArthur released a statement that he had no knowledge of any recommendation to attack Formosa with B-17s.

[55] The Japanese 14th Army began its invasion with a landing on Batan Island (not to be confused with Bataan Peninsula), 120 miles (190 km) off the north coast of Luzon, on 8 December 1941 by selected naval infantry units.

[56] Early on the morning of 12 December the Japanese landed 2,500 men of the 16th Division at Legazpi on southern Luzon, 150 miles (240 km) from the nearest American and Philippine forces.

Meanwhile, Hart withdrew most of his U.S. Asiatic Fleet from Philippine waters following Japanese air strikes that inflicted heavy damage on U.S. naval facilities at Cavite on 10 December.

Douglas MacArthur and Henry Stimson (United States Secretary of War) feuding with Admiral Hart over lack of US Navy submarine action.

The 26th Cavalry (PS) of the well-trained and better-equipped Philippine Scouts, advancing to meet them, put up a strong fight at Rosario but was forced to withdraw after taking heavy casualties with no hope of sufficient reinforcements.

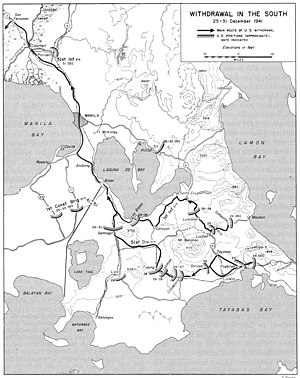

The next day, 7,000 men of the 16th Division hit the beaches at three locations along the shore of Lamon Bay in southern Luzon, where they found General Parker's forces dispersed and without artillery protecting the eastern coast, unable to offer serious resistance.

[65] He relieved Parker of his command of South Luzon Force and had him begin preparing defensive positions on Bataan, using units as they arrived; both the military headquarters and the Philippine's government were moved there.

Nine days of feverish movement of supplies into Bataan, primarily by barge from Manila, began in an attempt to feed an anticipated force of 43,000 troops for six months.

The South Luzon Force, despite its inexperience and equivocating orders to withdraw and hold, successfully executed "leapfrogging" retrograde techniques and crossed the bridges by 1 January.

Japanese air commanders rejected appeals by the 48th Division to bomb the bridges to trap the retreating forces,[69] which were subsequently demolished by Philippine Scout engineers on 1 January.

Despite 50% losses in the 194th Tank Battalion during the retreat, the Stuarts and a supporting battery of 75mm SPM halftracks repeatedly stopped Japanese thrusts and were the final units to enter Bataan.

On 30 December the American 31st Infantry moved to the vicinity of Dalton Pass to cover the flanks of troops withdrawing from central and southern Luzon, while other units of the Philippine Division organized positions at Bataan.

The amphibious landing was disrupted by a PT boat and contained in brutally dense jungle by ad hoc units made up of U.S. Army Air Corps troops, naval personnel, and Philippine Constabulary.

Beginning 28 March a new wave of Japanese air and artillery attacks hit Allied forces who were severely weakened by malnutrition, sickness and prolonged fighting.

The U.S. Philippine Division, no longer operating as a coordinated unit and exhausted by five days of nearly continuous combat, was unable to counterattack effectively against heavy Japanese assaults.

The older stationary batteries with fixed mortars and immense cannon, for defense from attack by sea, were easily put out of commission by Japanese bombers.

Early in 1942, the Japanese air command installed oxygen in its bombers to fly higher than the range of the Corregidor anti-aircraft batteries, and after that time, heavier bombardment began.

In December 1941, Philippines President Manuel L. Quezon, General MacArthur, other high-ranking military officers and diplomats and families escaped the bombardment of Manila and were housed in Corregidor's Malinta Tunnel.