Phineas Gage

[note 2] Little is known about his upbringing and education beyond that he was literate.[M]: 17,41,90 [M10]: 643 Physician John Martyn Harlow, who knew Gage before his accident, described him as a perfectly healthy, strong and active young man, twenty-five years of age, nervo-bilious temperament, five feet six inches [168 cm] in height, average weight one hundred and fifty pounds [68 kg], possessing an iron will as well as an iron frame; muscular system unusually well developed—having had scarcely a day's illness from his childhood to the date of [his] injury.

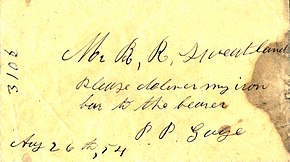

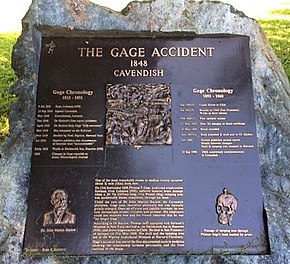

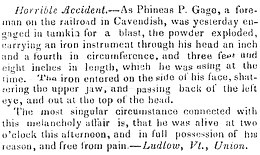

[M]: 18-22,32n9 His employers' "most efficient and capable foreman ... a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation",[H]: 13-14 he had even commissioned a custom-made tamping iron—a large iron rod—for use in setting explosive charges.[B1]: 5 [M]: 25 On September 13, 1848, Gage was directing a work gang blasting rock while preparing the roadbed for the Rutland & Burlington Railroad south of the village of Cavendish, Vermont.

[H]: 5 Gage was thrown onto his back and gave some brief convulsions of the arms and legs, but spoke within a few minutes, walked with little assistance, and sat upright in an oxcart for the 3⁄4-mile (1.2 km) ride to his lodgings in town.

)[L1]: 172 About 30 minutes after the accident, physician Edward H. Williams found Gage sitting in a chair outside the hotel and was greeted with "one of the great understatements of medical history":[M5]: 244 When I drove up he said, "Doctor, here is business enough for you."

[19] With Williams' assistance[note 6] Harlow shaved the scalp around the region of the tamping iron's exit, then removed coagulated blood, small bone fragments, and "an ounce or more" of protruding brain.

With a scalpel I laid open the [frontalis muscle, from the exit wound down to the top of the nose][H1]: 392 and immediately there were discharged eight ounces [250 ml] of ill-conditioned pus, with blood, and excessively fetid."

One month later, he was walking "up and down stairs, and about the house, into the piazza", and while Harlow was absent for a week Gage was "in the street every day except Sunday", his desire to return to his family in New Hampshire being "uncontrollable by his friends ... he went without an overcoat and with thin boots; got wet feet and a chill".

[19] By November 25 (10 weeks after his injury), Gage was strong enough to return to his parents' home in Lebanon, New Hampshire, traveling there in a "close carriage" (an enclosed conveyance of the kind used for transporting the insane).

[H]: 12 [M]: 92 Though "quite feeble and thin ... weak and childish"[23][M]: 93 on arriving, by late December he was "riding out, improving both mentally and physically",[H2] and by the following February he was "able to do a little work about the horses and barn, feeding the cattle etc.

He lost his job, and (wrote Harlow) as the seizures increased in frequency and severity he "continued to work in various places [though he] could not do much".[M]: 14 [H]: 16 On May 18, 1860, Gage "left Santa Clara and went home to his mother.

Previous to his injury, although untrained in the schools, he possessed a well-balanced mind, and was looked upon by those who knew him as a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation.

[H1]: 393 But after Bigelow termed Gage "quite recovered in faculties of body and mind" with only "inconsiderable disturbance of function",[B1]: 13-14 a rejoinder in the American Phrenological Journal— That there was no difference in his mental manifestations after the recovery [is] not true ... he was gross, profane, coarse, and vulgar, to such a degree that his society was intolerable to decent people.

[B]: 672,676,678,680 A reluctance to ascribe a biological basis to "higher mental functions" (functions—such as language, personality, and moral judgment—beyond the merely sensory and motor) may have been a further reason Bigelow discounted the behavioral changes in Gage which Harlow had noted.[M]: 169-70 [M1]: 838 (See Mind–body dualism.)

All this—in a land to whose language and customs Phineas arrived an utter stranger—militates as much against permanent disinhibition [i.e. an inability to plan and self-regulate] as do the extremely complex sensory-motor and cognitive skills required of a coach driver."

Adaptation had also to be made to the physical condition of the route: although some sections were well-made, others were dangerously steep and very rough.Thus Gage's stagecoach work—"a highly structured environment in which clear sequences of tasks were required [but within which] contingencies requiring foresight and planning arose daily"—resembles rehabilitation regimens first developed by Soviet neuropsychologist Alexander Luria for the reestablishment of self-regulation in World War II soldiers suffering frontal lobe injuries.[M10]: 645,651-52,655 [L2] A neurological basis for such recoveries may be found in emerging evidence "that damaged [neural] tracts may re-establish their original connections or build alternative pathways as the brain recovers" from injury.

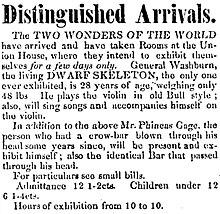

[M]: 107 [M10]: 646 But it has been misinterpreted[54] as meaning that Gage never held a regular job after his accident,[55][56][57] "was prone to quit in a capricious fit or be let go because of poor discipline",[58]: 8-9 "never returned to a fully independent existence",[59]: 1102 "spent the rest of his life living miserably off the charity of others and traveling around the country as a sideshow freak",[57] and ("dependent on his family" [60] or "in the custody of his parents")[61] died "in careless dissipation".

[V]: abstr Thiebaut de Schotten et al. estimated white-matter damage in Gage and two other case studies ("Tan" and "H.M."), concluding that these patients "suggest that social behavior, language, and memory depend on the coordinated activity of different [brain] regions rather than single areas in the frontal or temporal lobes.

"[T1]: 12 Harlow saw Gage's survival as demonstrating "the wonderful resources of the system in enduring the shock and in overcoming the effects of so frightful a lesion, and as a beautiful display of the recuperative powers of nature", and listed what he saw as the circumstances favoring it: 1st.

[H]: 18 Despite its very large diameter and mass (compared to a weapon-fired projectile) the tamping iron's relatively low velocity drastically reduced the energy available to compressive and concussive "shock waves".[M]: 56,68n3 [93][94] Harlow continued: 3d.

The point of entrance ... [The tamping iron] did little injury until it reached the floor of the cranium, when, at the same time that it did irreparable damage, it [created the] opening in the base of the skull, for drainage, [without which] recovery would have been impossible.

But to Gage's benefit, surgeon Joseph Pancoast had performed "his most celebrated operation for head injury before Harlow's medical class, [trepanning] to drain the pus, resulting in temporary recovery.

[H]: 18 Precisely what Harlow's "several reasons" were is unclear, but he was likely referring, at least in part, to the understanding (slowly developing since ancient times) that injuries to the front of the brain are less dangerous than are those to the rear, because the latter frequently interrupt vital functions such as breathing and circulation.

[M]: 126,142 For example, surgeon James Earle wrote in 1790 that "a great part of the cerebrum may be taken away without destroying the animal, or even depriving it of its faculties, whereas the cerebellum will scarcely admit the smallest injury, without being followed by mortal symptoms."

[M]: 128 [96] Ratiu et al. and Van Horn et al. both concluded that the tamping iron passed left of the superior sagittal sinus and left it intact, both because Harlow does not mention loss of cerebrospinal fluid through the nose, and because otherwise Gage would almost certainly have suffered fatal blood loss or air embolism.[R]: 640 [V]: 17 Harlow's moderate (in the context of medical practice of the time) use of emetics, purgatives, and (in one instance) bleeding[M]: 59-60 would have "produced dehydration with reduction of intracranial pressure [which] may have favorably influenced the outcome of the case", according to Steegmann.

[M]: 66 The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, for example, alluded to Gage's astonishing survival by referring to him as "the patient whose cerebral organism had been comparatively so little disturbed by its abrupt and intrusive visitor";[36] and a Kentucky doctor, reporting a patient's survival of a gunshot through the nose, bragged, "If you Yankees can send a tamping bar through a fellow's brain and not kill him, I guess there are not many can shoot a bullet between a man's mouth and his brains, stopping just short of the medulla oblongata, and not touch either.

"[103] As these and other remarkable brain-injury survivals accumulated, the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal pretended to wonder whether the brain has any function at all: "Since the antics of iron bars, gas pipes, and the like skepticism is discomfitted, and dares not utter itself.

[M]: 290 A similar concern was expressed as early as 1877, when British neurologist David Ferrier (writing to Harvard's Henry Pickering Bowditch in an attempt "to have this case definitely settled") complained that, "In investigating reports on diseases and injuries of the brain, I am constantly being amazed at the inexactitude and distortion to which they are subject by men who have some pet theory to support.

[M]: 250 Antonio Damasio, in support of his somatic marker hypothesis (relating decision-making to emotions and their biological underpinnings), draws parallels between behaviors he ascribes to Gage and those of modern patients with damage to the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala.

[K2]: 125,130n6 As Kihlstrom put it, "[M]any modern commentators exaggerate the extent of Gage's personality change, perhaps engaging in a kind of retrospective reconstruction based on what we now know, or think we do, about the role of the frontal cortex in self-regulation.

[note 7] The first portrait shows a "disfigured yet still-handsome" Gage[T] with left eye closed and scars clearly visible, "well dressed and confident, even proud" [W]: 343 and holding his iron, on which portions of its inscription can be made out.

(Position pointer over writing for transcription; click for full page.)