Phoronid

Phoronids (scientific name Phoronida, sometimes called horseshoe worms) are a small phylum of marine animals that filter-feed with a lophophore (a "crown" of tentacles), and build upright tubes of chitin to support and protect their soft bodies.

Unwanted material can be excluded by closing a lid above the mouth or be rejected by the tentacles, whose cilia can switch into reverse.

Two metanephridia filter the body fluid, returning any useful products and dumping the remaining soluble wastes through a pair of pores beside the anus.

One species builds colonies by budding or by splitting into top and bottom sections, and all phoronids reproduce sexually from spring to autumn.

An actinotroch settles to the seabed after about 20 days and then undergoes a radical change in 30 minutes: the larval tentacles are replaced by the adult lophophore; the anus moves from the bottom to just outside the lophophore; and this changes the gut from upright to a U-bend, with the stomach at the bottom of the body.

Some species live separately, in vertical tubes embedded in soft sediment, while others form tangled masses buried in or encrusting rocks and shells.

[5] There is good evidence that phoronids created trace fossils found in the Silurian, Devonian, Permian, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, and possibly in the Ordovician and Triassic.

From about the 1940s to the 1990s, family trees based on embryological and morphological features placed lophophorates among or as a sister group to the deuterostomes, a super-phylum which includes chordates and echinoderms.

[13] Their skins have no cuticle but secrete rigid tubes of chitin,[8] similar to the material used in arthropods' exoskeletons,[14] and sometimes reinforced with sediment particles and other debris.

[13] The cavity in the epistome is sometimes called the protocoelom, although other authors disagree that it is a coelom[18] and Ruppert, Fox and Barnes think it is built by a different process.

[1] Unwanted material can be excluded by closing the epistome (lid above the mouth) or be rejected by the tentacles, whose cilia can switch into reverse.

[13] Unlike many animals that live in tubes, phoronids do not ventilate their trunks with oxygenated water, but rely on respiration by the lophophore, which extends above hypoxic sediments.

[8] Podocytes on the walls of the blood vessels perform first-stage filtration of soluble wastes into the main coelom's fluid.

Two metanephridia, each with a funnel-like intake, filter the fluid a second time,[8] returning any useful products to the coelom[22] and dumping the remaining wastes through a pair of nephridiopores beside the anus.

[8] The trunk(s) have giant axons (nerves that transmit signals very fast) which co-ordinate the retraction of the body when danger threatens.

[8] Only the smallest species of horseshoe worms, Phoronis ovalis, naturally builds colonies by budding or by splitting into top and bottom sections which then grow into full bodies.

Some species are hermaphroditic (have both male and female reproductive organs[25]) but cross-fertilize (fertilize the eggs of other members[26]), while others are dioecious (have separate sexes[27]).

Early divisions of the egg are holoblastic (the cells divide completely) and radial (they gradually form a stack of circles).

[8] After swimming for about 20 days, the actinotroch settles on the seabed and undergoes a catastrophic metamorphosis (radical change) in 30 minutes: the hood and larval tentacles are absorbed and the juvenile body forms from the larva's metasomal sack.

Some occur separately, in vertical tubes embedded in soft sediment such as sand, mud, or fine gravel.

[1] Phoronopsis viridis, which reaches densities of 26,500 per square meter on tidal flats in California (USA), is unpalatable to many epibenthic predators, including fish and crabs.

These broadly effective defenses, which appear unusual among invertebrates inhabiting soft sediment, may be important in allowing Phoronopsis viridis to reach high densities.

[39] However, in 2006 Conway Morris regarded Iotuba and Eophoronis as synonyms for the same genus, which in his opinion looked like the priapulid Louisella.

[40] In 2009 Balthasar and Butterfield found in western Canada two specimens from about 505 million years ago of a new fossil, Lingulosacculus nuda, which had two shells like those of brachiopods but not mineralized.

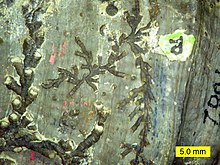

There is good evidence that species of Phoronis created the trace fossils of the ichnogenus Talpina, which have been found in the Devonian, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

[45] Hederellids or Hederelloids are fossilized tubes, usually curved and between 0.1 and 1.8 mm wide, found from the Silurian to the Permian, and possibly in the Ordovician and Triassic.

[6] From about the 1940s to the 1990s, family trees based on embryological and morphological features placed lophophorates among or as a sister group to the deuterostomes,[7] a super-phylum that includes chordates and echinoderms.

[47] Helmkampf, Bruchhaus and Hausdorf (2008) summarise several authors' embryological and morphological analyses which doubt or disagree that phoronids and brachiopods are deuterostomes:[6] Loricifera Nematoda Nematomorpha Arthropoda Onychophora Tardigrada Kinorhyncha Priapulida Dicyemida Orthonectida Gnathostomulida Chaetognatha Limnognathia Rotifera Gastrotricha Platyhelminthes Symbion Annelida Mollusca Nemertea Bryozoa Entoprocta Brachiopoda Phoronida From 1988 onwards analyses based on molecular phylogeny, which compares biochemical features such as similarities in DNA, have placed phoronids and brachiopods among the Lophotrochozoa, a protostome super-phylum that includes molluscs, annelids and flatworms but excludes the other main protostome super-phylum Ecdysozoa, whose members include arthropods.

[6][7] Cohen wrote, "This inference, if true, undermines virtually all morphology–based reconstructions of phylogeny made during the past century or more.

[7][55] The Lophotrochozoa are generally divided into: Lophophorata (animals that have lophophores), including Phoronida and Brachiopoda; Trochozoa (animals many of which have trochophore larvae), including molluscs, annelids, echiurans, sipunculans and nemerteans; and some other phyla (such as Platyhelminthes, Gastrotricha, Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, and Rotifera).