Photography of the Holocaust

[7] Some originated as routine administrative procedure, such as identification photographs (mug shots); others were intended to illustrate the construction and functioning of the camps or prisoner transport.

[12] A number of other photographs of the Jewish ghetto life come from Nazi personnel and soldiers, many of whom treated those locales as tourist attractions.

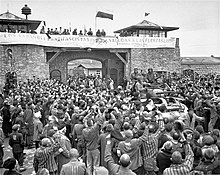

[5] Most Allied military photographers remain anonymous as they were seldom credited, unlike the press correspondents who published some of the first photo exposés of the camps; the latter included Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White, David Scherman, George Rodger, John Florea and William Vandivert.

[5] Because of the Cold War, many photographs made by the Soviets were treated with suspicion in the West, and received little coverage until decades later.

[6] Many photographs were destroyed, some accidentally, as collateral damage during the war, others on purpose, in attempts by perpetrators of the atrocities to suppress the evidence.

[5] Conversely, some Nazi photographs were stolen, hidden and preserved as evidence of atrocities by individuals such as Francisco Boix or Joe Heydecker.